They stood for a moment, ostensibly admiring a warlike effigy of the late Marshal Lannes, their eyes busy searching for Francis among the crowd of people, real and waxwork. Marianne shivered.

'It is cold in here.'

'Yes,' Jolival agreed, 'and our friend is late.'

Marianne made no answer. Her nervousness was increasing, possibly from the unnerving presence of so many all-too-lifelike wax dummies. The principal group, occupying the very centre of the room, represented Napoleon himself seated at table with all his family, with footmen in attendance. All the Bonapartes were there: Caroline, Pauline, Elisa and their stern Mama in her widow's weeds. But it was the wax Emperor himself that Marianne found most disconcerting. She had the feeling that his painted eyes were looking at her, seeing her conspiratorial air, and shame mingled with the fear of finding Francis suddenly before her made her want to turn and run.

Guessing her trouble, Arcadius stepped up to the imperial table and laughed.

'You have no idea how this dinner-table has reflected the history of France. It has seen Louis XV and his august family, Louis XVI and his august family, the Directorate and their august families and now here is Napoleon with his august family – although you will observe that the Empress is missing. Marie-Louise is still unfinished and besides, I have an idea they were going to cannibalize some parts of the Pompadour, who is now obsolete. What I do know is that this fruit has been here since Louis XV, and I should think that may well be the original dust!'

Jolival's commentary raised no more than a faint smile from Marianne. She was wondering what had become of Francis for, little as she wished to see him, she was also anxious to get the interview over and turn her back on a place she found depressing in the extreme.

Then, suddenly, he was there. Marianne saw him emerge from the darkest corner, behind the bath in which the dying Marat lay, struck by Charlotte Corday's knife. He, too, was dressed soberly, a brown hat pulled down low over his brow and his coat collar turned up to hide his face. He came quickly towards them and Marianne, who had never known him anything but confident and self-assured, was surprised to see him cast a swift, furtive glance around him.

'You are in good time,' he said curtly, without troubling to bow.

'You, on the other hand, are late,' Arcadius retorted drily.

'I was detained. You must forgive me. You have the money?'

'We have the money.' Again, it was Jolival who answered, and his grip on the wallet tightened a little. 'It does not appear, however, that you have Mademoiselle d'Asselnat.'

'You shall have her later. The money first. How can I be sure it is indeed in that wallet?' His hand went out towards the leather satchel.

'What is so delightful in dealing with persons of your sort, my lord, is the sense of trust which exists. See for yourself.' Arcadius slipped open the leather case, exposing the fifty notes, each for one thousand livres, then shut it swiftly, and tucked it back securely under his arm. 'There,' he said coolly. 'Now show us your prisoner.'

Francis moved irritably. 'I said later. I will bring her to your house tonight. For the present, I am in haste and may not linger here. It is not safe for me.'

That much was clear. His eyes were shifting continually, never meeting Marianne's. Now, however, she decided to take a hand. Laying her fingers on the wallet as if she feared that Arcadius might be overcome by some impulsive act of generosity, she said clearly: 'The less I see of you, the better I shall like it. My doors are closed to you, and you will gain nothing by coming to my house, alone or otherwise. We struck a bargain. You have seen that I have fulfilled my part of it. I call on you to fulfil yours. If not, we are back where we started.'

'Your meaning?'

'That you will get no money until you have restored my cousin to me.'

Lord Cranmere's grey eyes narrowed and began to glitter dangerously. His smile was unpleasant.

'Are you not forgetting something, my lady? If my memory serves me correctly, your cousin was only a part – a very small part of that bargain. She merely guaranteed that I should be undisturbed while you collected the money which will ensure that you in turn shall be left undisturbed.'

Marianne did not flinch before the barely concealed menace. Now that the swords were out, she had recovered all her poise and confidence, as she always did when a fight was in prospect. She permitted herself a small, contemptuous smile.

'That is not how I see it. Since the delightful conversation which you forced on me I have taken steps to ensure that I shall be left in peace. I am no longer afraid of you.'

'You are bluffing,' Francis said roughly. 'You need not. I am stronger at that game than you. If you did not fear me, you would have come here empty-handed.'

'I came only to recover my cousin. As for what you call bluffing, let me tell you that I have seen the Emperor. I spent several hours in his private office. If your information is as good as you pretend, you should have known that.'

'I do know it. I know also that you were expected to leave it under arrest.'

'Instead I left it to be politely escorted to my coach by his majesty's own valet,' Marianne countered with a coolness she was far from feeling. Determined to carry it through to the end, she went on: 'Distribute your pamphlets, my friend, they will not hurt me. And you will not get a penny from me until you return Adelaide.'

She knew his twisted nature too well not to feel deeply anxious, for he was not to be defeated so easily. Even so, Marianne could not help rejoicing a little inwardly as he hesitated, and when she saw a look of something very close to admiration on Arcadius's face she was sure that she was gaining an important advantage. It was vital that Francis should be made to believe that nothing mattered to her now but Adelaide, not so as to save the money, which Arcadius was still holding on to so grimly, but in order to render Lord Cranmere harmless in future. It was true that her future from now on would probably belong to Jason Beaufort but, just as she had recoiled in horror from the thought of involving Napoleon in a scandal of her making, so did she jib at offering Beaufort a wife who was an object of public infamy. It was bad enough to bring him one already pregnant by another man.

Lord Cranmere spoke suddenly.

'I wish I could return the old battle-axe to you. Unfortunately I have not got her.'

'What!'

Marianne and Arcadius spoke simultaneously. Francis shrugged sulkily.

'She has vanished. Slipped between my fingers. Escaped, if you prefer it.'

'When?' Marianne asked.

'Last night. When her supper was taken to her – her room, she was not there.'

'Do you expect me to believe this?'

All Marianne's hidden fears and anxieties exploded suddenly in one outburst of anger. That was too easy! Did Francis take her for a fool? He would collect the money and give nothing in return, except a dubious promise.

Equally angry, Francis flung back at her: 'You have no choice! I was obliged to believe it. I swear to you that she had vanished from the place where she was kept.'

'You are lying! If she had escaped she would have returned home.'

'I can only tell you what I know. I learned of her flight only a moment ago. And I swear, on my mother's grave —'

'Where had you hidden her?' Jolival interposed.

'In the cellars of the Epi-Scié, next door to here.'

Jolival gave a shout of laughter. 'With Fanchon? I had not thought you such a fool! If you want to know where she is, ask your accomplice. I'll swear she knows. No doubt she thinks her share of the profits are unworthy of her appetite!'

'No,' Lord Cranmere said curtly. 'Fanchon would not try such tricks on me. She knows that I should know how to punish her, once and for all. In any event, her anger at the old fidget's escape told its own tale. If you care for her, my dear, take care she does not fall into Fanchon's hands again. She certainly did her best to drive her to a fury.'

Marianne was well enough acquainted with Adelaide to guess how she had taken her abduction and imprisonment. Bold and cynical Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis might be, but it was, after all, possible that the unconquerable old maid had succeeded in making her escape. But if so, where was she? Why had she not made her way back to the rue de Lille?

Francis was growing impatient. For some time he had been glancing with increasing frequency towards the entrance where an enormous grenadier of the guard had now appeared, his head in its tall, red-plumed shako adorned with such a luxuriant growth of beard, such long, drooping moustaches, that it seemed to belong to some strange, hairy animal.

'An end to this,' Francis growled. 'I have wasted enough time already. I do not know where the foolish creature may have got to, but you will surely find her. The money!'

'No,' Marianne said firmly. 'You shall have that when I have my cousin.'

'Is that so? I think that you will give it to me now. Come, hand me that wallet, little man, at once, or it will be the worse for you.'

Marianne and Jolival had a sudden glimpse of the black muzzle of a pistol aimed from the shelter of Francis's coat directly at the girl's stomach.

'I knew you would make trouble over the old woman,' Lord Cranmere muttered grimly. 'Now, the money, or I fire. And do not move, you.' He nodded at Jolival.

Marianne's heart missed a beat. She read death in Francis's suddenly haggard face. Such was his lust for gold that he would not hesitate to kill, yet she refused to let him see her fear. She took a deep breath and drew herself up to her full height.

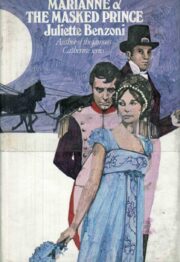

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.