'I am not denying his power, although I believe him to have feet of day, but how can you be sure that the future is his to dispose of? What will happen if he should ever fall? And what will happen to you and to the child? Our house will own no bastards, Marianne. You must make this sacrifice to your parents' memory, to the child, to yourself, even. Do you know how society treats an unmarried mother? Does the prospect attract you?'

'Ever since I realized, I have been prepared to suffer, to fight —'

'For what? For whom? To keep your hold on a man who has just been married to another?'

'He was obliged to marry – but I cannot.'

'And why not?'

'He would not permit it!'

The cardinal smiled at that.

'No? You do not know him. Foolish child, he would be the first to marry you off without delay, the moment he knew you carried his child. When one of his mistresses has been without a husband he has always made it his business to provide one. No trouble and no complications, that has always been his motto in affairs of the heart. He has enough of that at home.'

Marianne knew that what he said was true yet she was loth to admit the horrifying prospect which he laid before her.

'But, godfather, think! Marriage is something so important, so serious. Can you expect me to walk into it blindly to trust my whole life to a complete stranger, to put myself wholly in his power, day after day, night after night? Can't you see that my whole being would rise in revolt?'

'I understand first and foremost that you mean to do your utmost to remain Bonaparte's mistress, against all reason, and that you are no stranger to the realities of love. But it is possible to marry a man and live apart from him. From what I hear, the beautiful Pauline Borghese spends little enough of her time with poor Camillo. But I repeat, within a month you must be married.'

'To whom? To speak with such certainty, you must have someone in mind. Who is it?'

'That is my affair. You need not be afraid, the man I will choose for you, have already chosen, will not give you any cause for reproach. You will not lose the freedom you hold so dear, provided that you behave discreetly. But do not think I wish to constrain you. You may choose for yourself if you wish, and if you can.'

'How can I? You have forbidden me to tell anyone that I am expecting a child and I could not deceive anyone like that.'

'If there is a man, worthy of you and your name, who loves you enough to marry you in these circumstances, I should not oppose it. I will inform you where and when you are to come to me so that the marriage can take place. If you are accompanied by a man of your own choice, I will marry you to him. If you are alone, you will take the person I offer you.'

'Who will that be?'

'No more questions. I will say nothing more. You will have to trust me. You know I love you like my own daughter. Do you agree?'

Marianne nodded slowly, all her joy and pride evaporating in the face of grim reality. Ever since her discovery that she was pregnant, she had been carried along on the tide of exaltation that came from knowing she carried the Eagle's son within her and for a little while she had believed that this would enable her to hold her own before the world. But now she knew that her godfather had reason on his side, for however much she might scorn the opinion of others for herself, had she the right to force her child to carry the stigma of illegitimacy? There were those in society, she knew, who were not the children of those whose names they bore. The charming Flahaut was the son of Talleyrand and all the world knew it, but he owed his brilliant military career to the fact that his mother's husband had obliterated the stain that would have closed society's doors to him. Had not Marie Walewska returned to the snows of Walewice in order that her husband, the old count, might be able to acknowledge her unborn child? Marianne had sense enough to know that her own heart and her love must bend before necessity. She had, as the cardinal had said, no alternative. Yet at the very moment of acceptance which would seal her fate as surely as that final 'I will', she made one last effort to fight.

'I implore you, let me see the Emperor at least, speak to him… He may find a solution. Give me a little time.'

'Time is the one thing I cannot give you. We must act very quickly, and I can tell from your expression that you do not know when you will see Napoleon again. Besides, what is the use? I have told you: when you tell him, he will solve the problem in the only way possible, by marrying you to one or other of his own people, some fellow of dubious lineage, the son of an innkeeper or groom, and you, a d'Asselnat whose ancestors rode into Jerusalem with Godfrey of Bouillon and into Tunis with St Louis, will have to thank the creature humbly for taking you! The man I have in mind will ask nothing of you, and your son will be a prince.'

This harsh reminder of her position struck Marianne like a blow. She had a sudden vision of her father's proud, handsome face, the noble bearing of the portrait in the gilded frame, and then, set against the misty background of childhood, the less handsome but kindlier features of her Aunt Ellis. Surely their ghosts would be justified in turning their backs with anger on a child who could not accept the sacrifices which honour demanded? They had subdued their whole lives to that same sense of honour, even to the ultimate sacrifice. Marianne saw, as clearly as if they had risen suddenly out of the shadows of the library, the long line of her forbears, French and English, all of whom had fought and suffered to preserve intact their ancient name and the principle of honour. In that moment, she gave in.

'I agree,' she said firmly.

'In good time! I was sure you would.'

'Let it be understood clearly,' Marianne added quickly. 'I agree in principle to be married in a month, but between now and then I shall do all I can to find a husband of my own choosing.'

'I see no objection, providing always that you choose one who is worthy of us. All I ask is that you come, alone or otherwise, at the place and time I shall appoint. Let us call it a bargain, if you like. I will release you from Francis Cranmere, and you will protect your honour or pledge yourself to accept the man I shall bring you. Is it agreed?'

'A bargain is a bargain,' Marianne said. 'I pledge myself to honour this one.'

'Very well. In that case I shall set about fulfilling my part of the bargain.'

He moved to a tall writing desk which stood open in a corner, and taking a sheet of paper and a pen, wrote a few words. Meanwhile, Marianne poured herself another cup of coffee. She had no thought of going back on the words she had uttered, but one disturbing possibility occurred to her which she hastened to put into words.

'Supposing that I fail to find someone, may I ask one favour, godfather?'

He looked round at her without speaking, waiting to hear what she would say.

'If I must accept the husband of your choice, please, I beg of you, think of the child and do not make him bear the name of one who is his father's enemy.'

The cardinal smiled and dipped his pen in the standish with a tiny shrug.

'Not even my loyalty to the king would tempt me to anything so base,' he said with gentle reproach. 'You know me well enough. No such thought should ever have occurred to you.'

He finished what he was writing, sanded it, then folded it and affixed a wafer. He held it out to Marianne.

'Take this. I shall be leaving Paris in a few minutes and I do not like to leave you in this perilous situation. Tomorrow morning, take this letter to Lafitte, the banker. He will give you the fifty thousand livres which this English devil demands. That will grant you a breathing space, and allow you to recover that foolish Adelaide who seems to have grown no wiser with age.'

Amazement took away Marianne's breath as nothing else in that extraordinary interview had been able to do. She stared at the letter as if it were something miraculous, hardly daring to touch it. Her godfather's magnificent generosity left her speechless, especially as it forced her to overcome her resentment at his severity. She had thought him to be acting solely from a sense of duty and now, with a stroke of the pen, he had made his protection something warm and real. Her eyes filled with tears because for a while it had seemed as if he no longer loved her.

'There, take it,' the cardinal said gruffly, 'and don't ask unanswerable questions. You may have known me as poor as a church mouse but that does not mean I cannot find the money to save your life.'

There was, in fact, no time for any questions. The library door opened to admit a second cardinal. The newcomer, who was dressed in the robes of his office, was as small as the Cardinal San Lorenzo but his face, which was extremely handsome, had a pronounced air of nobility and bore a striking resemblance to the portrait over the fireplace.

'The coach and escort are at the door, my poor friend. We must go. Your horse is ready in the stable with your saddle-bags and such clothes as you need.'

'I am ready.' Gauthier de Chazay spoke almost joyously, gripping the newcomer's hands warmly. 'My dear Philibert, I can never thank you enough for sacrificing yourself like this. Marianne, I want to introduce you to Canon de Bruillard who, not content with offering me the shelter of his house, has carried friendship to the point of taking my place tonight.'

'Good heavens!' Marianne exclaimed. 'I had forgotten. You are to be sent to Rheims. But —'

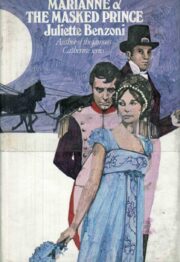

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.