'If, as you seem to think, this Abbé de Chazay forms one of the entourage of Pius VII, he must be at Savona and it will be an easy matter to trace him, and bring him to Paris. Your husband, however, is another matter.'

'Is it so difficult?' Marianne said quickly. 'If he and this Vicomte d'Aubécourt are one and the same?'

The Minister of Police had risen to his feet and was pacing the room slowly, his hands clasped behind his back. His progress had none of the Emperor's nervous energy. It was slow and thoughtful but, even so, Marianne found herself wondering why men felt it necessary to walk about in order to conduct a conversation. Was it a fashion started by Napoleon?

Fouché's perambulations brought him to a stop in front of the portrait of the Marquis d'Asselnat which brooded arrogantly over the gold and yellow harmonies of the salon. He stared at it for a while, as if waiting for an answer, then turned his heavy eyes on Marianne.

'Are you so sure?' he said slowly. There is no evidence to connect Lord Cranmere with the Vicomte d'Aubécourt.'

'I know that. But I should at least like to see him, to meet him.'

'Even yesterday, that would have been simple. The handsome Vicomte lodged in the rue de la Grange-Batelière, at the Hôtel Pinon. Since his arrival here he has been a constant visitor at the house of Madame Edmond de Périgord, having come armed with a letter of introduction from the Comte de Montrond who is at present in Anvers.'

Marianne nodded, a frown forming between her eyebrows. She experienced a twinge of doubt. Ever since the night before she had been acting on the assumption that Francis was the Vicomte d'Aubécourt. She had clung to the idea, as though to prove to herself that she was not suffering from hallucinations. But Francis as a visitor in the house of Talleyrand's niece? Madame de Périgord, by birth Princess of Courland and the richest heiress in all Europe, had been a real friend to Marianne when she was living as lectrice to Madame de Talleyrand. It was true that Marianne was not in her friend's company so often that she was familiar with all her connections, but she felt that she would have known if Lord Cranmere had begun to form part of Dorothée de Périgord's court.

'If it was at Anvers,' she said at last, 'that the Vicomte became acquainted with Monsieur de Montrond, that proves nothing. There have always been close ties between the Flemish and the English.'

'I agree, but I doubt whether, as an exile under police surveillance, the Comte de Montrond would dare to frank an Englishman disguised as a Fleming, and therefore a spy. Surely that would be taking too great a risk? I do not doubt that Montrond is capable of anything but only if it is worth his while and, if I remember rightly, the man you married gambled away your fortune on the spot. I have little reliance on Montrond's goodwill unless bolstered by financial incentives.'

It was all too logical, as Marianne was regretfully obliged to concede. Very well, Francis might not be concealing his identity under the name of the Flemish Vicomte, but he was certainly in Paris. At last, with a weary sigh, she said: 'Have you heard of any vessel come secretly from England?'

Fouché nodded. 'An English cutter put in by night a week ago on the isle of Hoedic to pick up a friend of yours, the Baron de Saint Hubert, whom you met in the quarries of Chaillot. Naturally, I did not hear of it until after the cutter had sailed out again, but the fact that it took someone off does not mean that it could not previously have landed another passenger from England.'

'How can we find out? Is…' Marianne paused, struck by a sudden thought which made her green eyes shine. Then she went on, more quietly: 'Is Nicolas Mallerousse still in Plymouth? He might know something about the movements of ships.'

The Minister of Police grinned wickedly and made her a mocking bow.

'Do me the kindness of believing that I thought of our worthy Black Fish long before you did, my dear. However, it so happens that just at present I am ignorant of the whereabouts of our remarkable son of the seas. There has been no news of him for a month past.'

'For a month?' Marianne exclaimed in a voice of anxious protest. 'One of your agents! And you are not worried about him?'

'No. If he had been caught or hanged I should have known. Black Fish has disappeared because he has found out something. He is following a trail, that is all. You must not worry so. Faith, my dear, I shall be thinking that you have a genuine kindness for your adopted uncle!'

'You may believe it,' Marianne told him curtly. 'Black Fish was the first person to offer me the hand of friendship when I was in trouble, without asking anything in return. That I cannot forget.'

The implication was sufficiently obvious. Fouché coughed and held his handkerchief to his lips, then took a pinch of snuff from his tortoiseshell box and finally changed the subject abruptly, saying: 'At all events, my dear, you may rest assured that I have put my best sleuths on the track of your phantom in blue: Inspector Pâques and my agent Desgrée. They are making inquiries about all foreigners in Paris even now.'

Marianne asked hesitantly, reddening a little at her own persistence: 'Have they – have they called on the Vicomte d'Aubécourt?'

Fouché's expression did not alter. Not a muscle moved in his pale face.

'They began with him. But the Vicomte left the Hôtel Pinon yesterday with all his luggage, leaving no address.'

Marianne sighed. Unless he showed himself, Francis was now about as easy to trace as a needle in a haystack. And yet he must be found at all costs. But to whom could she turn when Fouché confessed himself beaten?

As though he had read her thoughts, the minister gave her a thin smile and bowed to take his leave.

'Do not look so downhearted, Marianne, my dear. You know me well enough to know that I dislike admitting defeat. And so, without echoing Monsieur de Calonne's words to Marie-Antoinette: "If it is possible, it is done already, if impossible, it shall be done," I will be more modest and merely advise you not to lose hope.'

In spite of Fouché's soothing words, in spite of Napoleon's kisses and assurances, Marianne spent the next few days in a state of gloom and ill-temper. Nothing and no one could please her and herself least of all. Tormented, day and night, by the fires of jealousy, she prowled about her great house like a trapped animal. Yet she dreaded going out even more. At that moment she hated Paris.

The capital was a hive of preparations for the imperial wedding. Everywhere was festooned with garlands, streamers and fairy lights. On every public building, the black eagle of Austria nestled alongside the gold eagles of the Empire with a familiarity that raised growls from the veterans of Austerlitz and Wagram. With the aid of endless buckets of water and vigorous wielding of brooms Paris put on her holiday dress. The coming event hung over the city, fluttered in the depths of its innumerable streets, echoed through barracks and drawing-rooms to the music of fanfares and violins, filled shops and stores where the imperial portraits presided over piles of food and bales of silks and laces, brooded over tailors' and barbers' shops and dawdled with the idlers along the quais beside the Seine, where preparations for firework displays and illuminations were already under way. Most of all, it filled the sentimental hearts of the Parisian working girls for whom the Emperor had been suddenly transformed from the invincible god of battles to a Prince Charming. To Marianne, so much fuss made for a wedding which brought her nothing but grief seemed shocking and only depressed her more. Paris, which had lain at her feet a moment before, was now making ready to purr like a great, tame cat for the benefit of the hated Austrian, and she felt doubly betrayed. She preferred to stay shut up indoors, waiting for she knew not what: perhaps for the peals of bells and salvoes of guns that would tell her the worst had happened and the enemy was inside the city?

The court had left for Compiègne where the Archduchess Marie-Louise was expected on the twenty-seventh or twenty-eighth of March but the round of parties still went on. Marianne, now one of the most sought-after women in Paris, was showered with invitations which nothing could have persuaded her to accept. She would not even go to Talleyrand's, in fact there least of all because she could not bring herself to face the subtle irony of his smile. On the pretext of a non-existent cold, she stayed obstinately at home.

Aurélien, the porter at the Hôtel d'Asselnat, had strict instructions: with the exception of the Minister of Police or anyone sent by him and of Madame Hamelin, his mistress would see no one.

For her part, Fortunée Hamelin disapproved strongly of this behaviour. With her insatiable love of amusement, she was at a loss to understand her friend's voluntary retreat from the world merely because her lover was about to contract a marriage of state. Five days after Marianne's historic recital, she renewed her attack on her friend.

'Anyone would think you had been widowed or deserted!' she declared roundly. 'When in fact your position is a most enviable one. You are the adored and all-powerful mistress of Napoleon, yet without being a slave to him. This marriage releases you from the yoke of fidelity. Good God, you are young and ravishingly lovely, you are famous… and Paris is full of attractive men asking nothing better than to help you while away your solitude! I know at least a dozen who are wild for you. Shall I tell you their names?'

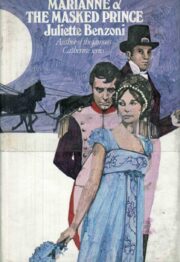

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.