'You know you meant every word, but I have forgiven you because you were right. But do not come near me. I must not touch you or I shall fail the Empress. We shall meet again.'

He went out, quickly, and Marianne returned to her seat by the fire. Her heart and mind felt empty, and she was suddenly chilled to the marrow. Something told her that things could never be the same again between them. There were the words which had been spoken, words which would be followed by absence, and silence. She experienced a piercing regret for the miraculous days at the Trianon when all quarrels had been dissolved at last in kisses. But nothing could bring back the Trianon. From now on, love would have a bitter taste of loneliness and renunciation. Would there ever be a return to the state of pure happiness which had been hers for those few weeks? Or must she learn from now on to give without looking for anything in return?

Around her, the palace had grown silent as a desert. Constant's footsteps, approaching across the bare wooden floor outside, seemed to come from the depths of time. She felt suddenly faint. Her heart was beating fast and a cold sweat had broken out all over her body. She tried to rise but a dreadful feeling of sickness made her sink back, panting, on the couch. It was there that Constant found her, her eyes enormous, her face like wax, her handkerchief to her lips. She stared up at him desperately.

'I don't know what is the matter with me. I feel so ill, dreadfully ill. I was all right a moment ago.'

'You are very pale. What is the matter?'

'I am so cold, my head is spinning, but worst of all, I feel so dreadfully sick.'

The valet busied himself silently, fetching eau-de-Cologne, bathing Marianne's temples and making her drink a cordial. The sickness went as swiftly as it had come. Little by little, the colour came back into her cheeks and before very long she felt as well as ever.

'I can't think what came over me,' she said, smiling gratefully up at Constant. 'I thought I was dying. Perhaps I should see a doctor.'

'You should see a doctor, mademoiselle, but I do not think the matter is very serious.'

'What do you mean?'

Constant picked up the bottles and napkins he had brought with studious care, then he smiled kindly, with a hint of sadness in his smile.

'I mean it is unfortunate that mademoiselle was not born to the purple. It would have saved us from this Austrian marriage, which promises nothing but trouble. All the same, I trust that it will be a boy. It would give the Emperor so much pleasure.'

CHAPTER SIX

The Bargain

The revelation of her condition overwhelmed Marianne and, at the same time, gave her fresh courage and an extraordinary sense of triumph. She was not so innocent as to imagine that if the discovery that she was expecting a child had come a few months earlier it would have prevented the Austrian marriage. Napoleon had known, after Wagram, that Marie Walewska was carrying his child and it had made no difference. He could have married her: he loved her and she came of a noble family. Yet he had made no move because, however nobly born, Marie, like Marianne herself, was not a princess and so not sufficiently well-born to found a dynasty. Yet it gave Marianne a strange, rather agonizing joy, to think that the imperial blood was at work somewhere deep inside her, while Napoleon was exerting himself to impregnate his plump Viennese and obtain the heir he longed for. Whatever he did now, he was bound to Marianne by ties of flesh and blood, and so nothing could destroy her exultant happiness in the knowledge that she bore his child, not even the stigma attached to the word 'illegitimate'. Marianne was prepared to confront gossip, scorn and social ostracism for the sake of the few ounces of humanity slowly forming within her.

These thoughts sustained her as she drove, in the carriage which had been brought for her, towards the rue Chanoinesse, prepared to face what would undoubtedly be one of the hardest battles of her life.

She was all too familiar with her godfather's uncompromising royalism, his rigid moral principles and the inflexibility of his private code of honour, and she knew that her confession would have its painful moments.

At this late hour, the rue Chanoinesse was in darkness, except for two street lamps hung on cables across the road. The metal-shod wheels rang on the big cobblestones that paved the road between the silent, secretive houses where the canons of Notre Dame lived behind their barred windows. The twin shadows of the cathedral towers stretched, grotesquely elongated, across the ancient rooftops, making the dark night seem darker still.

A belated priest, accosted politely by Gracchus-Hannibal, pointed out the house of Monsieur de Bruillard which was easily recognizable by the tall, slender tower rising from its court-yard. It was also one of the few houses that still showed a light. The canons went early to bed, leaving the streets free for the ruffians who infested the old part of the city.

Considerably to Marianne's surprise, the canon's house breathed none of that smell of cold wax and musty papers which she associated with a churchman's dwelling. A footman in dark livery with nothing monkish about him conducted her through a pair of salons furnished with a discreet elegance, and brought her to a closed door before which the Abbé Bichette was standing guard, head hunched between his shoulders and hands clasped behind his back. At the sight of the visitor, the faithful secretary hurried forward with an exclamation of relief which told Marianne she was expected.

'His Eminence has asked three times if you had yet arrived. His impatience is so great that he will have no one near him, not even myself.'

'Especially yourself,' Marianne thought, deciding that she could not have borne with the Abbé's company for more than fifteen minutes.

'You must know,' Bichette continued, lowering his already hushed voice still further, 'that we are to leave Paris before dawn.'

'What? So soon? My godfather said nothing of this to me.'

'His Eminence was not then aware of it. Early this evening Monsieur Bigot de Preameneu, the Minister concerned with religious affairs, informed us that we were no longer welcome in the capital and should prepare to leave.'

'But where to?'

To Rheims, where the refractory members of the Curia are – er – detained. It is most unfortunate and quite unjust.'

At that moment the door before which they were standing was thrown open and the cardinal appeared, looking now much more like Marianne's recollections of the Abbé de Chazay in a suit of black somewhat shabbier than the footman's.

'Bichette!' he said severely. 'I am old enough to recount my misfortunes to my god-daughter in my own way. You waste time with your chattering, when you would be better employed sending a message to the kitchen for coffee, a great deal of coffee, very strong, and do not disturb me again until Monsieur Bruillard tells you he is ready. Come in, my child.'

The last words were addressed to Marianne. She entered and found herself in a small but comfortable library, its pale woodwork, rich bindings and bright Beauvais tapestries no more ecclesiastical in feeling than the rest of the house. The portrait of a pretty woman smiled mischievously from a fine oval gilt frame, flanked by a pair of tall ormulu candlesticks, while over the fireplace the young Louis XV in coronation robes seemed to invest the whole room with his royal presence.

The cardinal observed Marianne's surprise at the sight of the portrait and smiled.

'De Bruillard is the natural son of Louis XV and the fair lady you see above the desk. Hence this portrait, which is not often seen in Parisian houses nowadays. But never mind that now. Come and sit by the fire and let me look at you. I have been striving ever since I left you to think what miracle could have brought you to Paris and how it comes about that I, who married you to an Englishman, now find you on the steps of the Tuileries in the company of an Austrian.'

Marianne smiled a little nervously. The moment she dreaded had arrived. She was determined to face up to it at once, without any attempt at prevarication.

'Do not try, godfather dear, you will never guess. No one could ever imagine the things that have happened to me since we parted. Indeed, there are times when I wonder if it is all really true and not just a dreadful nightmare.'

The cardinal drew up a chair facing Marianne's. 'What do you mean? I have had no news from England since your wedding day.'

'Then you know nothing – nothing at all?'

'No, I assure you. First tell me, what has become of your husband?'

'No,' Marianne said quickly. 'Please, let me tell you in my own way. It will not be easy.'

'I thought that I had taught you not to be put off by what is difficult.'

'And I shall not be. But first you must understand one thing. The Hôtel d'Asselnat belongs to me. The Emperor gave it to me. I – I am that opera singer you mentioned.'

'What—?'

The cardinal had risen to his feet in astonishment. His homely face was a stone mask, devoid of all expression. But in spite of the shock she knew it must be to him, Marianne felt suddenly lighter. The most difficult part was over.

Without a word, the cardinal crossed to a corner of the room where an ivory crucifix hung in a red velvet frame and stood for a moment, upright and not obviously praying, but when he turned and made his way back to Marianne some of the colour had returned to his face. He sat down again, only this time, perhaps in order to avoid looking at his god-daughter, he turned towards the fire, holding out his thin hands to the blaze.

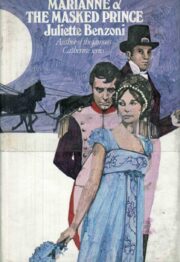

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.