Marianne wished that curtsey might never end. When at last she lifted her eyes to the newly-wedded pair, the picture of happiness which they presented cut her to the heart. Without a glance for the brilliant assembly, Napoleon was leading his wife to her seat with every sign of the most tender consideration, even dropping a kiss upon the hand which he retained in his own as he too seated himself. Moreover, he continued to lean towards her, talking privately, with a complete disregard of his surroundings.

Marianne stood by the piano, stupefied, uncertain what to do. The court was seated now, waiting for the Emperor's signal for the concert to begin.

But Napoleon continued his smiling tête-à-tête and it seemed to Marianne that the low dais on which she stood was a kind of pillory to which she had been bound by the cruel whim of a neglectful lover. She had a wild impulse to run from that opulent room and its hundreds of pairs of eyes. If only it had been possible. Up above, in the royal box, the Comte de Ségur was bending respectfully before the Emperor, asking for a sign. It was given him, carelessly, without so much as a look, and translated instantly into a solemn rap of his staff.

At once, like an echo, there came the sound of Paer's baton tapping on the desk. Alexandre Piccini at the piano struck up the opening chords, taken up a moment later by the violins. His anguished glance told Marianne that her distress was evident. She caught sight of Gossec in his corner, looking anxious, his face intent, as if in prayer. Surely no one had ever seen the Emperor treat a famous artiste with such contempt?

Fortunately, anger came to Marianne's rescue. Her first song was to be the great aria from La Vestale, the Emperor's favourite. Taking a deep breath to calm the frantic beating of her heart, she attacked the piece with a passionate energy that left her audience gasping. Her voice soared with such a fierce intensity as she expressed the despair of Julie, the vestal virgin condemned to burial alive, that even this worldly audience was shaken. In her determination to make the Emperor attend to her, she sang better than she had ever done. On the final notes, her voice rang with such poignant misery that a chorus of spontaneous, frenzied applause broke out, in defiance of protocol which decreed that the sovereign alone should give the signal for it. But the skill of the singer had electrified her audience.

She looked up at the royal box, eyes sparkling with hope, but no, not only was Napoleon not looking at her, he did not even appear to have noticed that she had been singing. His head was bent towards Marie-Louise, talking softly to her. She was listening to him downcast, a simpering smile on her lips and her face so flushed that Marianne could only conclude with rage that he was making love to her. She nodded sharply to Paer to begin the second piece, an aria from The Secret Marriage by Cimarosa.

Never, surely, was the Italian composer's light and delicate music sung with such grim feeling. Marianne's green eyes were fixed on the Emperor, as if they would force his attention. Her heart swelled with uncontrollable anger, depriving her of all sense of proportion, all self-control. How dared that stupid Viennese sit there smiling like a cat at a cream pot? How could anyone have the nerve to claim that she liked music?

Marie-Louise's love of music must have been confined to the airs of her own country for she was not only not listening but, right in the middle of the aria, she giggled suddenly. It was a childish giggle but too loud to escape notice.

Every drop of blood left Marianne's face. She stopped singing. For a moment, her glittering eyes swept the rows of heads before her, all with the same expectant expression, then with her own head held proudly erect, she marched off the dais and, in the astounded pause which followed, she left the salle des Maréchaux before anyone, even the men at the doors, could think to stop her.

Her head on fire and her hands like ice, she walked stiffly on, ignoring the storm which broke out behind her. The one idea in her fevered brain was to depart for ever from the place where the man she loved had dealt such a cruel blow to her pride, to go home and bury her grief in the old home of her family and wait, wait for what was bound to follow such an act: the Emperor's wrath, arrest, perhaps even imprisonment. But for the moment, nothing mattered to Marianne. So furious was she that she would have walked to the scaffold without so much as a glance.

A voice called after her.

'Wait! Mademoiselle! Mademoiselle Maria Stella!'

She went on down the grand staircase as if nothing had happened. Not until Duroc caught up with her at the foot of the stone steps did she finally stop and turn with an expression of complete indifference to face the Grand Marshal, who seemed on the verge of an apoplexy, his face as scarlet as his splendid uniform.

'Have you gone mad?' He gasped, struggling to regain his breath. 'Such conduct – in the Emperor's presence!'

'Whose conduct was the more shocking, mine or the Emperor's – or that woman's, at least?'

'That woman? The Empress? Oh —'

'I know no empress other than the one consecrated by the Pope, at Malmaison! As for that caricature you call by the name, I deny her right to make a fool of me in public. Go and tell your master that!'

Marianne was beside herself with rage. Her voice rang coldly among the stone arches of the old palace with a clarity that, to Duroc, was highly embarrassing. Was that a shadow of a smile under the moustaches of the grenadier on duty at the foot of the stairs? Forcing a sternness into his voice which he was far from feeling, he took Marianne's arm and began: 'I am afraid you will have to tell him yourself, mademoiselle. My orders are to take you to the Emperor's private office to await his pleasure.'

'Am I under arrest?'

'Not to my knowledge, not yet at any rate.'

The implication of this was not reassuring but Marianne did not care. She expected to pay dearly for her outburst but if she were to be given the chance to unburden herself to Napoleon once and for all, she meant to do so without mincing words. If she were going to prison, it might as well be worth while. At least it would save her from the machinations of Francis Cranmere. The Englishman would have to wait until she was released to pursue his plans, since he would gain nothing by destroying her altogether. There remained Adelaide, but here Marianne was confident she could rely on Arcadius.

It was, therefore, with a degree of serenity that the Emperor's rebellious subject entered the familiar room, calmed for the moment by the prospect of an interview with its owner, and heard Duroc give orders to Rustan, the Mameluke guard, to permit no one to enter, nor to allow Mademoiselle Maria Stella to communicate with anyone. This last recommendation even drew a smile from her.

'I am a prisoner, you see?' she said gently.

'No, I have told you. But I would rather not have young Clary yapping outside the door like a lost lapdog. I must warn you to be prepared for a long wait. The Emperor will not come until the reception is over.'

With no other response than a faint but highly impertinent shrug of her shoulders, Marianne sat down on the little yellow sofa drawn up to the fire where she had first set eyes on Fortunée Hamelin. The thought of her friend succeeded in finally calming Marianne. Fortunée was too experienced in the ways of men ever to have feared Napoleon. She had convinced Marianne that to show fear was the worst mistake she could make, even, or indeed especially, if he were in one of his famous rages.

A deep silence, broken only by the crackling of the fire, descended on the room. It was warm and cosy, in spite of its absence of luxury. This was the first time Marianne had been alone there and feminine curiosity impelled her to take stock of it. It was comforting to be there, where every object reminded her of the Emperor. Passing over the files of documents, the red morocco folders with the imperial arms stamped on them, the large map of Europe flung down on the desk, she took pleasure in handling the long white goose quill that stood in the porphyry inkstand, the ormulu watch-stand in the shape of an eagle, and a chased gold snuff-box with an ill-fitting lid from which the fragrance of the contents escaped. Each object proclaimed his presence, even the crumpled black cocked hat thrown down in a corner, in a temper probably, and not long ago either, since Constant had not yet retrieved it. Was it the matter of the carriage which had provoked that outburst? For all her courage, Marianne could not help feeling an unpleasant tingling sensation up her spine. What would he be like later?

The time began to seem suddenly very slow. Marianne had the scent of battle in her nostrils and she wanted it to begin. Tired of roaming about the padded silence of the room, she picked up a book that lay on the desk and returned to her seat. It was a much worn copy of Caesar's Commentaries, bound in green leather stamped with the imperial arms. It was so thumbed and annotated, the margins so heavily scored and filled with a cramped, nervous hand, that it had become wholly unreadable for anyone but the author of those notes. Marianne let it fall on to her lap with a sigh, although her hand continued to caress the worn leather, as though unconsciously searching for the trace of another hand. The cover grew warm, almost human under her touch. Marianne closed her eyes, the better to savour the feeling.

'Wake up.'

Marianne started and opened her eyes. Candles had been lighted in the room and outside it was dark. Napoleon stood before her with folded arms, a brooding anger in his eyes.

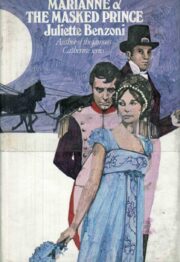

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.