'This is impossible,' he muttered. 'How is it you are here, in France, entering this palace in the company of an Austrian?'

'Prince Leopold Clary und Aldringen,' the young man introduced himself promptly, clicking his heels and bowing.

'Charmed,' the cardinal responded automatically, still pursuing his own thoughts. 'What I mean is, how do you come to be in Paris, when the last time we met… Where is —'

Marianne broke in hurriedly, guessing with horror what he was about to say. As it was, Clary had certainly heard that unfortunate 'Lady Marianne', so much was clear from his expression, and that was sufficiently alarming.

'I will explain everything later, godfather. It is a long story and too complicated to explain here. But tell me what you are doing yourself. You were about to leave on foot, if I guess rightly?'

'I shall do as the others do, of course,' the cardinal declared. We came here, my brothers and I, and were informed by the Grand Marshal of the Palace that we were to leave again at once, since his majesty churlishly refused to receive us!'

'Eminence,' begged the Abbé Bichette, rolling his eyes in horror, 'be careful what you are saying.'

'What's that? I shall say what I please! I was shown the door, was I not? They even paid us the compliment of sending away our carriages so that we might present the riff-raff of Paris with the amusing spectacle of fifteen cardinals trotting home on foot, like grocers, with their robes tucked up out of the dust! I hope the good people of Paris appreciate their Emperor's courtesy!'

Monsignor de Chazay's face was as red as his robe and his usually well-modulated voice was growing alarmingly shrill. Clary intervened.

'If I understand correctly,' he said stiffly, 'your Eminences saw fit to absent yourselves from the wedding of our Archduchess? Naturally, the Emperor could not allow such an affront to go unpunished. I confess, I had expected the worst.'

'You need have no fear, the worst will certainly come. As for the Archduchess, I assure you, monsieur, we regret it deeply, but it is our duty to his Holiness to adhere to the position which he has adopted. The marriage between Napoleon and Josephine has not been annulled in Rome.'

'In other words,' Prince Clary said, 'in your eyes, our Princess is not married?'

Marianne, horrified at the prospect of a fresh scandal, hastened to intervene.

'For pity's sake, gentlemen! Not here – godfather, you cannot walk home like this. Where are you living?'

'With a friend, Canon Philibert de Bruillard, in the rue Chanoinesse. I do not know if you are aware of it, my child, but our family's house is now in the possession of an opera singer who enjoys the favour of Napoleon. Consequently I am unable to live there.'

Marianne felt as if she had been struck. Each word seemed to wound her to her very soul. She drew back, white to the lips, groping for Leopold Clary's arm and leaning on it heavily. Without that support she would probably have fallen in the dust that was already marking the red slippers of the prince of the Church. Those few words measured the gulf which had opened between her and her childhood days. She was seized by a sudden terror that, in his innocence and old-world chivalry, Clary would spring to her defence and utter the truth that she was that very opera singer in person. Marianne meant to tell her godfather the truth, the whole truth, but in her own time, not in the midst of a crowd.

Fighting desperately to control herself, she managed a pale smile, while her grip tightened on the Prince's sleeve.

'I will visit you tonight, if you will let me. Meanwhile, Prince Clary's carriage will take you home.'

The young Austrian stiffened.

'But – my dear, what will the Emperor say?'

At this she lost her temper, finding in her anger a release for her deepest emotions.

'You are not the Emperor's subject, my dear Prince. And may I remind you that your own sovereign is on excellent terms with the Holy Father. Or did I not understand you correctly?'

Leopold Clary drew himself up, as if in the presence of the Emperor Franz himself.

'You understood quite correctly. Eminence, my carriage and my servants are at your service. If you will do me the honour…'

Without turning, he clicked his fingers to summon the coachman. The carriage rolled obediently up to the little group and one of the grooms sprang down to open the door and let down the steps.

The cardinal's bright eyes took in the pale-faced girl in the blue dress and the Austrian prince, nearly as white as she in his white uniform. His clear gaze held a world of questions, but Gauthier de Chazay uttered none of them. Royally, he extended his hand with the great sapphire ring for Clary's lips to kiss, then turned to Marianne who sank to her knees, heedless of the dust.

'I will expect you this evening,' he said, as she rose. 'Ah, I was forgetting. His Holiness, Pius VII, has conferred a cardinal's hat on me. I am known, and admitted to France, by the name of San Lorenzo-fuori-muore.'

Moments later, the Austrian carriage passed the gateway of the Tuileries, followed by the envious gaze of the remaining princes of the Church who, one by one, were resigning themselves to departing homewards on foot, their followers at their heels, with the hope of finding a public vehicle for hire on the way. Marianne and Clary stood watching the Cardinal San Lorenzo out of sight.

Mechanically, Marianne dusted the silver embroideries of her dress with her gloves, then turned to her companion.

'Shall we go in?'

'Yes, although I wonder what our reception will be. Half the people in the palace saw us offer a carriage to a man whom the Emperor regards as his enemy.'

'You wonder too much, my friend. Let us go in and we shall see. There are many things in life, believe me, which are infinitely more to be feared than the Emperor's anger.' She spoke the words through clenched teeth, thinking of what her godfather would say that evening when he heard the truth.

The prospect threw a slight shadow over the joy which she had felt a little while before at seeing him again, but could not altogether destroy it. It was so good to find him, especially at a time when she had such urgent need of his help. What he would say would hardly be pleasant, she knew, he would not look kindly on her new career as a singer, but in the end he would surely understand. No one had more understanding and human sympathy than the Abbé de Chazay and why should the Cardinal San Lorenzo be any different? Marianne remembered suddenly how her godfather had always distrusted Lord Cranmere. He would surely pity the misfortunes of one who, as he himself had said a moment ago, was as dear to him as his own child.

No, all things considered, Marianne found herself looking forward to the evening with more hope than foreboding. Gauthier de Chazay, Cardinal San Lorenzo, would have no difficulty in persuading the Pope to annul a marriage which dragged like a heavy chain round his god-daughter's neck.

This was the first time Marianne had entered the state apartments of the Tuileries. The salle des Maréchaux, where the concert was to be held, overwhelmed her with its size and magnificence. Once the guardroom of Catherine de Medici, it was a vast chamber rising to two storeys below the dome of the central section of the palace. On the level of the upper storey, facing the dais where the performers were to stand, was a huge box in which the Emperor and his family would soon take their places. This box was supported on four gigantic caryatids completely covered in gold leaf, representing armless female forms in classical draperies. From either side of the box, balconies ran right round the room, entered by means of archways draped, like the doors and windows elsewhere in the hall, in red velvet scattered with gold bees. The roof was a rectangular dome, the corners occupied by massive, gilt trophies, with, in the centre, a colossal chandelier of cut crystal. The dome itself was adorned with allegorical frescoes and, to enhance the warlike aspect of the room, the lower walls were decorated with full-length portraits of fourteen marshals, interspersed with busts of twenty-two generals and admirals.

Although the vast room and the balcony were full of people, Marianne felt lost, as though in some huge cathedral. The noise was like an aviary run mad, drowning the sounds of the musicians tuning up their instruments. So many faces moved before her eyes that for the moment, in the shifting blur of colours and flashing jewels, she was incapable of recognizing any that she knew. At last, she saw Duroc, magnificent in the violet and silver of the Grand Marshal of the Palace, coming towards her, but it was to Clary that he spoke.

'Prince Schwartzenberg is asking for you, monsieur. If you will be good enough to join him in the Emperor's private office.'

'In the Emperor's —'

'Yes, monsieur. I should not keep him waiting, if I were you.'

The young Prince met Marianne's eyes with a look of alarm. This summons could mean only one thing: the Emperor was already aware of the incident of the carriage and poor Clary was in for a dressing down. Unable to let her friend bear the blame for her action, Marianne intervened.

'Monsieur, I know what the Prince is summoned to his majesty for, but as the matter concerns myself alone, let me be allowed to go with him.'

The Duke's frown did not lighten and the look he bent on the young woman before him was stern.

'Mademoiselle, it is not my place to admit to his majesty's presence those who have not been sent for. I am in fact instructed to escort you to Messieurs Gossec and Piccini who await you with the orchestra.'

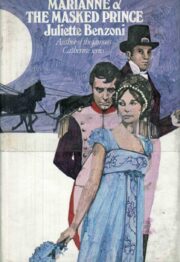

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.