'I am uneasy, my dear Maria. I have not seen the Emperor since the night of his marriage, the day before yesterday, and I fear this reception may not go altogether smoothly. I am not yet well-acquainted with his majesty, but I saw him in such anger the other day as he came from the chapel —'

'Anger? Coming out of the chapel? But what happened?' Marianne asked, her curiosity aroused at once.

Leopold Clary smiled and dropped a rapid kiss on her hand.

'Of course, you were not there, you deserted me. Well, I must tell you that as the Emperor entered the chapel he noticed that only twelve of the twenty-seven cardinals invited were actually present. Fifteen had failed to appear and, believe me, their absence was extremely noticeable.'

'But why should they deliberately stay away?'

'That it was deliberate, there can be no doubt, alas. And it has caused us at the embassy a good deal of embarrassment. You know how the Emperor stands with the Pope? He holds his Holiness a prisoner at Savona and did not feel himself bound to apply to him for a dissolution of his previous marriage. It was all done here in Paris. Now the absence of these princes of the Church casts some doubt on the legality of our Archduchess's marriage. It is all most unpleasant, and Prince Metternich was far from pleased at those fifteen empty stalls.'

'Bah!' Marianne retorted, not without a certain satisfaction. 'You knew all this before your Princess ever left Vienna. You could have insisted that his Holiness should authorize the Empress Josephine's divorce. Don't tell me you did not know the Pope had excommunicated the Emperor a year ago?'

'I know,' Clary agreed gloomily. 'We all know. Since then we have been defeated at Wagram, we needed peace, a breathing space, and we were simply not strong enough to refuse Napoleon's request.'

'You mean this marriage was more than you dared hope for?' the young woman countered with a cruelty regretted as soon as it was out, when she saw her friend's unhappy face and heard him sigh.

'It is never much fun to be beaten. In any case, this marriage is a fact and however painful it may be to us to see the Church treat one of our princesses in this cavalier fashion, we cannot entirely blame her. That is what worries me. All the bishops and cardinals have been invited to this concert, you know.'

Marianne did know and had dressed accordingly. Her gown of heavy, dull-blue silk, embroidered with palm-leaves in silver, was made high to the throat, framing the rows of pearls which she had inherited from her mother and which were the only jewels she had kept, all the rest having been handed to Jolival the day before. The dress had long sleeves, half-concealing her hands. She waved those hands now, carelessly.

'You are tormenting yourself for nothing, my friend. Why should these cardinals come to the concert any more than to the wedding?'

'Because your Emperor's invitations are more in the nature of commands and they may not dare to absent themselves a second time. But I fear the reception they will get from Napoleon. If you had seen the way he looked at the empty seats in the chapel, you would be as anxious as I am. My friend Lebzeltern said it sent cold shivers down his spine. If it comes to an open breach, our position will be highly uncomfortable. The Emperor Franz is on close terms with his Holiness.'

This time, Marianne said nothing. She felt little interest in the qualms of conscience suffered by Austria. Besides, they were arriving. The carriage had passed the pont des Tuileries and the guards outside the Louvre and was approaching the high, gilded railings enclosing the cour du Carrousel. But from here, progress became increasingly laborious. A large crowd had collected round the palace and was pressing up against the railings. Some people had even climbed up to get a better view, in spite of all efforts to restrain them. There were sounds of exclamations and laughter.

'Crowds, whether Viennese or Parisian, are always equally strange and uncontrollable,' observed the Prince. 'I hope they will let us pass.'

But the ambassador's groom had already announced his master's carriage and the guards were busy clearing a way for it. The coachman urged his horses inside and the occupants of the carriage were able to see for themselves the extraordinary spectacle which had been attracting the laughter of the Parisian crowd. There, in the great courtyard, among the soldiers standing to attention, the palace officials and the grooms and servants controlling the arrival of the guests, were fifteen cardinals in ceremonial dress, the skirts of their purple robes thrown over their arms, wandering about at random, their secretaries trotting at their heels like a flock of terrified black chickens. Only a Parisian crowd could have found anything humorous in the sight of these stately, red-robed figures, moving about apparently aimlessly; neither soldiers nor officials seemed to pay them the slightest attention.

What does it mean?' Marianne asked. Turning to Clary, she saw that he had gone very white and that his heavy side-whiskers were trembling uncontrollably.

'I am afraid that this is the way the Emperor has chosen to manifest his displeasure. What else does he intend, I wonder?'

The carriage drew up at the steps. A footman opened the door. Clary got out hurriedly and held out his hand to his companion.

'Come inside, quickly. I would give a great deal not to have seen this.'

'To spare your conscience further qualms?' Marianne said, with irony. 'What is the creature which behaves so? An ostrich, is it not? Perhaps we should call you Ostrichians?'

'What a dreadful pun! There are times when I wonder if you hate me.'

This was a question Marianne had already asked herself many times but at that moment it had ceased to interest her. Her eyes had come to rest on one of the cardinals, a small man whose billowing red robes made him look like an overblown rose. He had his back to her and was standing on the bottom step, apparently talking earnestly with a thin, dark Abbé who was bending his tall figure to hear what was being said. Something about the little cardinal fascinated Marianne. The shape of his head, perhaps, above the ermine collar, or the colour of the grey hair under the round red cap? Or then again, was it the exquisitely-shaped hands as he waved them in the heat of his argument? All at once, he looked round and at the sight of his profile a cry was torn from Marianne.

'Godfather!'

The blood rushed to her face as she recognized the man who, throughout her childhood, had shared her heart with her Aunt Ellis, and although she had no more than a brief glimpse of his face, she could not be mistaken now. The little cardinal was Gauthier de Chazay.

'What was that?' Clary said anxiously regarding her. 'You know—'

But Marianne was no longer listening. She had forgotten his presence as she had forgotten the place where they stood, even the person she now was. She was, as she had been long ago, little ten-year-old Marianne, running as hard as she could the whole length of the park at Selton when she saw the Abbé de Chazay coming slowly up the avenue. She felt no surprise, even, at finding the little Abbé, perpetually short of money, now dressed in the red robes of a cardinal. With him, all things were possible, even the most improbable. In a sudden rush of joy she did quite naturally what she had always done, she picked up the skirts of her magnificent dress in both hands and hurried after the two priests who were already beginning to move away, careless of the curiosity she aroused. A moment later, she had caught up with them.

'Godfather! Oh, this is wonderful – wonderful!'

Laughing and crying at once, she threw herself into the arms of the little cardinal who had barely time to see who it was before she had her arms round his neck.

'Marianne!'

'Yes, it is I, it is I indeed! Oh, godfather, this is wonderful!'

'Have I taken leave of my senses? Marianne? Here? What are you doing in Paris?'

He had extricated himself and was now holding her at arm's length gazing at her in a delighted astonishment much stronger than concern for his dignity. His homely features shone with joy.

'I am not dreaming! It is really you! Good heavens, child, how lovely you have grown! Let me kiss you again.'

And before the horrified gaze of the thin priest and of Prince Clary who had followed his companion automatically, the cardinal and the girl began hugging one another again with an enthusiasm which left their mutual feelings in no doubt.

The thin priest must have formed his own ideas about these unorthodox transports, for he coughed gently and tapped the cardinal's shoulder.

'Forgive me, your Eminence, but it might perhaps – that is – er – the circumstances – your Eminence must be aware that people are staring.'

This was true. Palace servants, guards and prelates were all staring transfixed at the odd little scene: the black-dad priest and the splendid Austrian officer watching the little cardinal and the richly-dressed girl. There were smiles and whispers. Leopold Clary alone seemed conscious of embarrassment. Gauthier de Chazay shrugged magnificently.

'Don't be a fool, Bichette. Let them look if they care to. Do you realize that I have found my long-lost child, the child of my heart, I mean. Allow me to introduce you. Marianne, my child, this is the Abbé Bichette, my faithful secretary. And you, my friend, meet my god-daughter, Lady Marianne —'

He stopped short, realizing what he had been about to say in his delighted enthusiasm. The smile faded, as if a curtain had been drawn across by some invisible hand and he looked at Marianne in sudden disquiet.

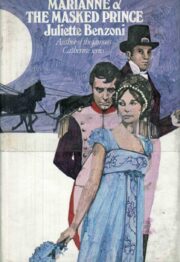

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.