Constant shifted his eyes and moved away to pick up his hat from a chair. He stood for a moment turning it between his hands but he looked up at Marianne at last and there was a touch of sadness in his smile.

'Yes, he said that, but it means little beyond an expression of relief. Remember, she is a Habsburg, the daughter of the man he defeated at Wagram. He might have looked for pride, resentment, even rejection. This placid princess is reassuring, she is a little awkward and nervous, like a country cousin. I think he is profoundly grateful. As for love, if he was as much in love with her as you would like to imagine, would he have thought of you today? No, Mademoiselle Marianne, believe me, come and sing for him, if not for her. And tell yourself that it is Marie-Louise who should fear comparison, not you. Will you come?'

Defeated, Marianne bowed her head in consent.

'I will come. You may tell him so. And tell him,' she added with an effort, indicating the bag of coins, 'that I thank him.' It hurt her to accept the money but as matters stood at present it was very welcome and Marianne could not afford the luxury of refusal.

Arcadius weighed the bag in his hands and laid it back on the writing-table with a sigh.

'The Emperor is generous. It is a good sum, but not nearly enough to satisfy our friend. We need more than twice as much and unless you ask his Majesty to prove himself more generous still…'

'No!' Marianne cried, flushing. 'Not that! I could not! Besides, I should have to explain, tell him everything. Then the Emperor would set the police on Adelaide's track – and you know what will happen when Fouché's men come on the scene.'

Arcadius felt in his waistcoat pocket and produced a pretty snuff box of tortoiseshell bound with gold, a present from Marianne, and helped himself luxuriously to a pinch of snuff. The time was nearly nine o'clock and he had just returned to the house, apparently no more ready to explain his mission than he had been at the start. He restored the box to his pocket and smoothed the little bump it made there with his fingers, dreamily, as if in contemplation of a particularly agreeable idea. At last he said: 'We need have no fear of that happening. None of Fouché's agents will lift a finger to find Mademoiselle Adelaide, even if we were to ask them.'

'What do you mean?'

'You see, Marianne, when you described your conversation with Lord Cranmere, one thing struck me: the fact that this man, an Englishman travelling under a false name and in all probability a spy, was able not merely to go about Paris in broad daylight – and in the company of a woman notoriously suspect – but seemed to be in no dread of apprehension by the police. He told you, did he not, that if you had him arrested he would be released at once, with apologies?'

'Yes, I told you.'

'Did it seem to you odd? What did you make of it?'

Marianne clasped her hands and took two or three quick turns about the room.

'Well, I don't know – I did not think about it at the time.'

'Not then or later, I think. But I was curious to know a little more and so I paid a visit to the quai Malaquis. I have some – er – connections among the minister's staff and I found out what I wanted to know, the reason the Vicomte d'Aubécourt is not afraid of the attentions of the police. Quite simply, he is hand in glove with Fouché, perhaps even in his pay.'

'You are mad!' Marianne gasped. 'Fouché would never be hand in glove with an Englishman.'

'Why not? The Duke of Otranto has, at this present moment, excellent reasons for remaining on good terms with an Englishman. He has certainly extended a warm welcome to your noble husband.'

'But – he promised to find him for me?'

'Promises cost nothing, especially when you have no intention of keeping them. I think I can promise you that Fouché not only knows quite well where the Vicomte d'Aubécourt is to be found but also who is passing under that name.'

'This is absurd – fantastic!'

'No. It is politics.'

Marianne felt the world reeling about her ears. She clapped her hands to her head to steady her whirling thoughts. What Arcadius was saying was so shattering that she felt lost on the roads which were suddenly opening out before her, filled with lurking shadows and traps laid before her feet at every step. She made an attempt to see sense in the confusion.

'But this is impossible – the Emperor —'

'Who said anything about the Emperor?' Jolival broke in roughly. 'I said Fouché. Sit down for a moment, Marianne. Stop fluttering about like a frightened bird and listen to me. At this present moment, the Emperor has reached the peak of his success and power. Almost nothing stands against him. Ever since Tilsit, the Tzar swears he loves him like a brother. The Emperor Franz has given him his daughter to wife. He holds the Pope in his hand and his Empire stretches from the Elbe and the Drava to the Ebro. His only enemies now are the wretched Spaniards and their ally, England. Now Joseph Fouché has one burning ambition, and that is to be, after the Emperor, the most powerful man in Europe. He means to become Napoleon's understudy, his right-hand man, and in order to achieve this he has conceived a plan of almost suicidal boldness. His aim is to bring about a reunion between France and England, her last and most deadly enemy. For several months he has been secretly employing trusted agents to negotiate with the Government in London, through the medium of the Dutch king. Let him once find any basis for agreement with Wellesley and he will be able to say to Napoleon: "I have brought you England, willing at last to come to terms with you, on this or that condition." Of course, Napoleon will be furious at first – or pretend to be, because in fact it will remove the biggest thorn from his hide and set his dynasty securely on the throne. Morally speaking, he will have triumphed. That is why Lord Cranmere has nothing to fear from Fouché. He is certainly sent from London.'

Marianne had listened attentively to Jolival's long explanation. Now she said quietly: 'But there is still the Emperor and, to make Fouché do his duty, which is to pursue enemy agents, it is enough to tell his majesty what is in the wind...'

Her old resentment against Fouché, as the man who had coldbloodedly made use of her when she was a friendless fugitive, made her by no means reluctant to inform Napoleon of the secret machinations of his trusted Minister of Police.

'I think you would be making a mistake,' Arcadius said seriously. 'I realize, of course, that you are shocked to find one of the Emperor's ministers so exceeding his authority, but an agreement with England would be the best thing that could happen for France. The continental blockade has brought a host of troubles: the war in Spain, the imprisonment of the Pope, incessant levies of troops to defend our ever-growing frontiers.'

Marianne had no answer to this. She never ceased to be surprised at Arcadius's extraordinary ability to acquire information on all subjects, yet, this time, he seemed to her to be going a little far. To have such knowledge of state secrets, he must have been intimately concerned in them. Unable to conceal her thoughts, she said point blank: 'Tell me the truth, Arcadius. You yourself are one of Fouché's agents, are you not?'

The Vicomte laughed outright, but it seemed to Marianne that there was something guarded in his laughter.

'But my dear girl, all France dances to the minister's piping: you, me, Fortunée, the Empress Josephine…'

'Don't laugh at me. Tell me the truth.'

Arcadius stopped laughing and, crossing to his young friend's side, gently patted her cheek.

'My dear child,' he said softly, 'I am no one's agent but my own, except perhaps for the Emperor and yourself. But when I need to know something, I take steps to find it out. And you cannot imagine how many people are involved in this business already. I would swear, for example, that your friend Talleyrand is not unaware of it.'

'Very well,' Marianne sighed irritably. 'In that case, since Lord Cranmere is so powerful, how can I protect myself against him?'

'For the present, I have told you: pay up.'

'I shall never find thirty thousand livres in three days.'

'Exactly how much have you?'

'Beside these twenty thousand, a few hundred livres. There are my jewels of course – those given me by the Emperor.'

'Out of the question. He would never forgive you if you sold them, or even pledged them. The best thing would be to ask him to make up the sum. As for your day to day expenses, you have a number of engagements offered you which will take care of that.'

'I will not ask him for the money at any cost,' Marianne broke in, so decisively that Jolival did not press the point.

'In that case,' he sighed, 'I see only one way —'

'What?'

'Go and put on one of your prettiest dresses, while I get into knee breeches. I think Madame Hamelin gives a party tonight and you are invited.'

'But I do not mean to go.'

'But you are going, that is, if you want your money. For there we shall certainly find our charming Fortunée's lover, Ouvrard, the banker. Apart from the Emperor, I can think of no quarter where you are more likely to obtain money than from a banker's coffers. This one, moreover, is extremely susceptible to the charms of a pretty woman. He may agree to advance you the sum and you can repay him with the next proof of the Emperor's generosity, which will soon be forthcoming.'

Marianne could not like Arcadius's plan. The idea of using her charms to extract money from a man was repugnant to her, but she told herself firmly that Fortunée would be there to oversee the transaction. Besides, she had no choice. Meekly, she departed to her room to change.

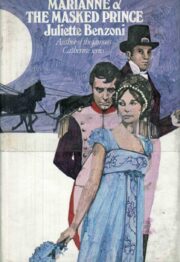

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.