'On what?'

'On your latest Austrian conquest. I am delighted to see you have decided to take my advice. You will find the faithlessness of men much easier to bear when you have another all ready to hand.'

'Not so fast,' Marianne said, laughing. 'I have no intention of doing more than being seen in Prince Clary's company. His great attraction, you see, is that he is Austrian. I like the idea of amusing myself with a countryman of our new sovereign.'

Fortunée and Adelaide laughed gaily.

'Is she really as ugly as they say?' Adelaide asked eagerly, selecting one of the preserved fruits provided for her cousin.

Marianne did not answer at once. She half-closed her eyes, as if it helped her to conjure up the vision of the intruder, and a wicked smile curved the soft lines of her mouth. The smile was all woman.

'Ugly? No, not exactly. It is hard to say, really. She is more – commonplace.'

Fortunée sighed exaggeratedly. 'Poor Napoleon. What has he done to deserve that! A commonplace wife, when he loves only the exceptional!'

'If you ask me, it is the French who have done nothing to deserve it,' Adelaide exclaimed. 'A Habsburg is bound to be a disaster.'

'Well, they do not seem to think so,' Marianne said with a laugh. 'You should have heard the cheering in the streets at Compiègne!'

'At Compiègne, maybe,' Fortunée said meditatively. They have very little excitement there, except for hunting parties. But something tells me Paris will not be so easily impressed. The only people who will welcome her arrival here will be those circles who see her as the Corsican's doom and the avenging angel of Marie-Antoinette. The people are far from delighted; they worshipped Josephine and they have no love for Austria.'

Gazing at the crowd filling the place de la Concorde on the following Monday, the second of April, Marianne reflected that Fortunée might well be right. It was a holiday crowd, dressed in its smartest clothes and rippling with excitement, but it was not a happy crowd. It stretched all along the Champs Elysées and was thickest around the eight pavilions which had been erected at the corners of the square. It washed up against the walls of the Garde-Meuble and the Hôtel de la Marine but there was none of the throbbing gaiety of a great occasion.

Yet the weather was fine. The depressing downpour had ceased quite suddenly at dawn, the clouds had been swept away and a bright spring sunshine bathed the opening buds of the chestnut trees in sparkling light. Straw bonnets and hats trimmed with flowers burgeoned on the heads of the Parisiennes and their male escorts were resplendent in pale pantaloons and coats of innumerable subtle shades. Marianne smiled at the outburst of seasonable elegance. The population of Paris seemed bent on demonstrating to the new arrival that the French knew how to dress.

Seated with Arcadius and Adelaide in her carriage near one of the prancing stone horses, Marianne had an excellent view of the scene. Flags and fairy lights were everywhere. The Tuileries railings had been newly gilded, the fountains were running with wine and free buffets loaded with food had been set up in red – and white-striped tents under the trees of the cours La Reine, so that everyone might have a share in the imperial wedding feast. Orange trees, glowing with fruit, stood in tubs round the square in readiness for the night's illuminations. Later, when the wedding ceremony had been performed in the great salon carré of the Louvre, the Emperor's loyal subjects would be free to consume four thousand eight hundred pies, twelve hundred tongues, a thousand joints of mutton, two hundred and fifty turkeys, three hundred and fifty capons, the same number of chickens, three thousand or so sausages and a host of other things.

Jolival sighed and helped himself delicately to a pinch of snuff. 'By tonight, their majesties will reign over a nation of drunkards, not to mention the overeating there will be.'

Marianne did not answer. She found the holiday atmosphere both entertaining and irritating. All up and down the Champs Elysées was a sea of little booths containing attractions of all kinds, tiny open-air theatres, dancing, peepshows and shies. From Marianne's carriage, as from any of the others which had come to view the spectacle, it was possible to overhear an endless succession of vulgar jokes which were a clear indication of the prevailing mood. What had passed at Compiègne was common knowledge and no one doubted that Napoleon was about to lead to the altar a woman whose bed he had been sharing for a week, although the civil ceremony had taken place only the day before at Saint-Cloud.

It was noon and the cannon had been roaring for a good half-hour. At the far end of the long vista of the Champs Elysées, lined with the pale green haze of the young chestnut leaves, the sun fell on the huge triumphal arch made of wood and canvas which had been set up in place of the yet unfinished monument to the glory of the Grande Armée. The imitation arch looked well in the spring sunshine, with its brand new flags and the great bouquet placed there by the workmen, the trompe l'oeil reliefs on the sides and the inscription to 'Napoleon and Marie-Louise' from The City of Paris'. The thing was amusing enough, Marianne thought, but it was by no means pleasant for her to see the names of Napoleon and Marie-Louise so coupled together.

The red plumes on the tall shakos of the Grenadier Guards waved all along the route, alternating at the intersections with the red and green cockades of the Chasseurs. Orchestras and bands everywhere were playing the same tune, a popular song called 'Home is where your Heart is' which soon got on Marianne's nerves. It seemed an odd choice for the day when Napoleon was marrying the niece of Marie-Antoinette.

Suddenly, Arcadius's hand, gloved in pale kid, was laid on Marianne's.

'Don't move and don't turn round,' he said softly. 'But I want you to try and take a peep into the carriage that has just drawn up beside us. The occupants are a man and a woman. The woman is a stranger to neither of us but I do not know the man. He has an air of breeding and is very handsome, in spite of a scar on his left cheek – a scar that might have been caused by a sword cut—'

With a supreme effort, Marianne sat still, but her hand trembled under Jolival's. She raised the other to her lips and yawned ostentatiously, as if the long wait for the bridal procession were becoming tedious. Then, slowly and with perfect naturalness, she turned her head very slightly, enough to bring the interior of the neighbouring carriage within her field of vision.

It was a black and yellow curricle, brand new and extremely smart, bearing the obvious signature of Keller, the fashionable coach-builder in the Champs Elysées. There were two people inside. The elderly woman was splendidly dressed in black velvet trimmed with fur, and Marianne was not surprised to recognize her old enemy, Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis. It was the woman's companion, however, who drew her eyes and although her heart missed a beat the cause was not surprise but an unpleasant sensation more akin to revulsion.

This time, there could be no mistake. It was Francis Cranmere and no phantom conjured up by a fevered imagination. Marianne saw the familiar, almost-too-perfect features, set in an expression of perpetual boredom; the stubborn brow and the rather heavy chin supported by the folds of the high, muslin cravat; the powerful body, exquisitely dressed and preserved, as yet, from corpulence by physical exercise. His clothes were a blend of subtle dove-grey shades, relieved by a dramatic black velvet collar.

They must have followed us,' Jolival murmured. 'I will swear they have come for no other purpose. See, the man is looking at you. It is he, is it not? Your husband?'

'It is he,' Marianne agreed. Considering the turmoil within her, her voice was curiously calm. Her proud, disdainful green eyes met and held Francis's grey ones without flinching. She was discovering, agreeably, that now that she was face to face with him in fact, the vague terrors which had haunted her ever since his appearance at the theatre had melted away. It was the sense of some obscure, unspecified menace which had frightened her. She was afraid of the unknown but the prospect of an open fight left her in full possession of her faculties.

She read the mockery on the faces of Francis and his companion but the steadiness of her gaze did not falter. She was conscious of no great astonishment at seeing them together, or at finding the hideous crone dressed up like a duchess. Fanchon was cunning and dangerous, a kind of female Proteus. However, Marianne had no intention of discussing her affairs in front of Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis. Her self-respect would not permit the interference in her life of a woman who had been publicly branded a criminal. She decided that it would be wiser to postpone her desire to be done with Lord Cranmere once and for all.

She was already leaning forward to tell Gracchus-Hannibal, at present lording it in his new livery on the box, to extricate them from the crowd and drive home when the door was pulled open and Francis himself appeared, hat in hand, bowing with mocking courtesy. He was smiling but the eyes that rested on Marianne's face were hard as stone.

'Permit me,' he said lightly, 'to pay my respects to the queen of all Paris.'

Beneath the bonnet of lilac silk and white Chantilly lace that matched her expensively-tailored carriage dress, her face was very white but she put out one gloved hand to restrain Arcadius who had started forward to bar Francis's way.

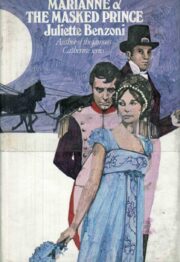

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.