'You cannot do it. You are suffering from severe bronchitis. You must stay in bed and, what is most important, you must avoid all risk of catching cold again, for you would be risking your life.'

Even then she persisted, with the obstinacy of the very sick. Her determination was strengthened now by fear of these vast, inhospitable wastes of country with their endless snows and sunless, hopeless skies. She wanted to escape from them as soon as she could. The thought had become an obsession with her, fixed in her head like the barbed arrow of some demon archer. To tear it out now might be to tip her over into madness.

What she longed for was to see the sea again, even in a port so northerly as Danzig.

The sea was her friend, a friend that had always spared her life, even though it had more than once put it in danger. The sound of the sea washing the shores of England had lulled her through most of her childhood and for years now it had carried all her dreams, her hopes, her love. In the depths of her illness, Marianne was convinced that somehow everything would be miraculously all right, her health restored and her sufferings at an end, as soon as she came safe to a harbour.

Barbe, worried as she was, could still understand the sick girl's overriding longing to be gone.

'Do what you can for her,' she said to Moïse. 'I will try to make her stay another two or three days by telling her how tired I am, but I don't think it will be any good.'

In fact it was five days before Marianne declared that she would wait no longer and by that time the fever had almost left her.

'I must go to Danzig,' she kept repeating. 'I know I shall be strong enough for that. But I must go quickly – as quickly as I can. Something is waiting there for me.'

She could not for the life of her have explained just why it was that she felt so certain. Barbe, in any case, put it down to her illness. But as she had lain there with the fever on her, her mind wandering in vague feverish dreams, Marianne had gradually convinced herself that her fate was waiting for her there, in that Baltic port where she had so longed to go with Jason. Perhaps, after all, that fate would take the form of a ship…

Barbe was no actress but she was still trying manfully, and with no success at all, to portray a woman in the last stages of exhaustion, when she received the first direct order she had ever had from her mistress. She was to have the kibitka ready to leave tomorrow, Marianne told her, and when Barbe tried to argue she was told that Kovno, the next and final stage of the kibitka's journey, was no more than twenty leagues ahead of them. Marianne was in haste, too, to hand over the precious package entrusted to her to Solomon's cousin. It was beginning to weigh on her mind. In her weakened state, her mind had begun to play superstitiously with the belief that those jewels, taken from a church, might be a cause, if not the only one, of all her sufferings. Moreover, those pearls had only narrowly escaped ending in the Berezina along with herself.

Barbe found her orders all the more distressing because they were interrupted by frequent fits of coughing. As a last resort it seemed to her that the physician's voice might be more effective than her own, but much to her surprise she found, when she went in search of Moïse, that his eagerness to detain them in his house had waned considerably. Unless, that was, they were willing to remain there alone and exposed to possible unpleasantness.

'I am leaving,' he explained. 'I and my family. We shall quit Vilna very soon for Riga where we have a house and kinsfolk. It is unwise for us to remain longer here if we care for our possessions – and even for our lives.'

When Barbe expressed astonishment, he told her of the latest news which was going about the country. It was disastrous news for the French, because it said that Napoleon's army, broken and starving after a series of catastrophic engagements, was now falling back on Vilna as its one port in a storm. It was said also that there had been some kind of battle that was more like a massacre when the fleeing army had tried to cross the Berezina at the very spot where Barbe and Marianne had made the crossing. The bridges were all destroyed and but for the heroism of the Engineers, who had succeeded in erecting makeshift ones, the whole army might by then have been destroyed or taken prisoner. Many had got across, including a host of civilians following the army, but since then repeated attacks by the cossacks had caused more tragic gaps in the ranks.

'As far as I can gather,' Moïse said, 'all this took place on about the day that you reached here. Since then, Napoleon has been making for Vilna as fast as he can, dragging in his train a host of desperate and starving men to descend on us like locusts. They will want houses and huge quantities of food and we shall be ravaged to supply them. And we Jews most of all, for we are always the first to suffer when there is looting or requisitioning. Therefore I would rather take my family and my most precious possessions out of harm's way while there is still time. They can burn my house after that if they please. It will be no more than an empty shell. So that is why,' he went on gravely, 'I must, for my own sake, so far fail in hospitality as to beg you to resume your journey. All I can suggest is that you follow us to Riga—'

'No, no. We may as well continue on our own road. But can you give us some protection for my mistress, to save her as far as possible from the dangers of a relapse. In this cold weather it is still to be feared.'

'Of course, of course! You shall have furs, and lined boots, even a stove which you may keep alight in the kibitka, and food, of course.'

'Thank you. But what of you, will you be permitted to leave? The French governor—'

Then Moïse Chakhna did something very odd for one of his quiet, even rather reserved, disposition. He shook his fist, as though at some invisible third person present in the room.

'The governor? His grace the Duke of Bassano does not believe the rumours of disaster. He is threatening imprisonment for anyone who spreads them. He himself is thinking of giving a ball. But I, I know that every word of it is true and I am going!'

The next day, the kibitka resumed its journey to Kovno and the crossing of the Niemen. True to his promise, the physician had provided the two travellers generously with everything they needed against the cold, nor were his provisions at all unnecessary because now, at the beginning of December, temperatures dropped, suddenly and dramatically. The thermometer fell to 20° below zero, the rivers froze and the carriage wheels no longer sank into the soft snow. The horse, too, moved surefootedly over the hard surface, although they dared not travel very fast because of the danger of overturning the top-heavy vehicle altogether.

To help maintain its balance, Barbe wrapped woollen rags about her boots and resigned herself to walking beside it, for she was desperately afraid of seeing it capsize and throw Marianne out on to the ice.

Fortunately, quite contrary to her fears, Marianne seemed to be rather better than otherwise. The fever had not returned and her cough had loosened and the fits were not so long. But to be on the safe side, Barbe made her stay wrapped up in her furs, so that only her eyes showed, bright and feverish.

In this way they travelled for three days and nights before they came within reach of the Niemen. On the evening of the third day, Barbe was so worried by the increasing cold that she refused to stop at all, especially since by this time they were in the midst of an exposed plain with no possible shelter anywhere.

'We may as well go on now,' she declared, when they stopped as they had to for something hot to eat and drink. Scattering the remains of their fire with her foot, she added: 'Tomorrow morning we shall be in Kovno.'

And so all that night Barbe walked on, carrying a lantern to light the way. She walked on doggedly until the devil sent a new ordeal to try her. Two hours before dawn, when they were actually within sight of Kovno, one of the rear wheels of the kibitka struck some unseen obstacle and broke. The kibitka lurched violently and ground to a halt.

Marianne, who had been dozing, was woken by the shock. She poked her head outside and saw Barbe's face, white and shining with mutton fat, loom up, moonlike, in the light of the lantern. In spite of the grease, which was designed to prevent her skin from chapping, little crystals of ice had formed in her eyebrows and under her nose, where her breath had frozen. Her whole face was a picture of despair.

We've broken a wheel,' she wailed. 'We can't go on! No, no—' as she saw Marianne preparing to descend. 'Don't get out! It's much too cold. You'll catch your death.'

'I'll catch it either way if we have to stay here very much longer. Are we very far from Kovno?'

'Two or three versts at most. You can see from here where the Wilia runs into the Niemen. The best thing might be—'

She had no time to say what the best thing might be, however, for just then a horseman swept round a bend in the road and bore down on them. He just managed to avoid the kibitka, which was occupying the crown of the road, but was no sooner past than he struck the bank and fell. He was up again almost at once and helping his horse back on its feet. Then, cursing volubly in French, he made his way back to the vehicle.

'Thunder of God! What in hell's going on here? You damned—' He had drawn his pistol and seemed inclined to use it. Barbe cried out quickly before he could take aim.

'It will do you no good to kill us. We've broken a wheel and we've troubles enough of our own!'

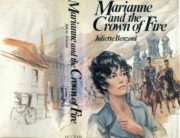

"Marianne and the Crown of Fire" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire" друзьям в соцсетях.