'Ha! I suppose you think you had his blessing when you became a whore!' he yelped.

'Maybe not, 'though I always kept myself for soldiers so in that way I was serving my country. But supposing I were to go back into service for good, I could only do so with a really great lady. Now if your good lady were not merely your good lady – if she were a duchess, say, or even a princess, well, in that case, even supposing she should be homeless and without a penny to bless herself with – even wanted by the law, then I'd not refuse. Oh, by no means! Yes,' Barbe went on dreamily, 'I can see her as a princess. It would suit her down to the ground.'

Beyle and Marianne stared at one another in dismay. It was obvious where Barbe was leading. The woman knew their secret. Going about the city as she did each morning to see what she could pick up in the way of food, she must have seen the bills pasted up everywhere with their accurate descriptions of Marianne. And now, not satisfied with the thousand livres offered as a reward, she was intending to blackmail her employers.

Seeing that Beyle was too much overcome by this blow of fate to answer, Marianne took the matter into her own hands. Going right up to Barbe she looked her straight in the eyes.

'Very well,' she said icily. 'I am completely at your mercy. But, as you yourself have observed, I have no money, only—' She broke off, biting her lip as she realized that, stupidly, she had been on the point of mentioning the diamond. But that did not belong to her. It as hers only in trust and she had no right to use it even to save herself.

'Only what?' Barbe inquired innocently.

'Only the knowledge that I have done nothing to deserve that I should be hunted. But I will not argue with you. Since you have discovered who I am – the door is there! You may run to the nearest soldiers and give me up. The Emperor will be delighted to pay you the thousand livres when you tell him you have found the Princess Sant'Anna.'

She had expected the woman to sneer at her, perhaps utter some coarse words of abuse, and then make a dash for the door, but nothing of the sort occurred. Barbe certainly began to laugh but, to Marianne's immense surprise, her laughter was as candid as it was free of all malice. Then she came to Marianne and took her hand and kissed it, in the best tradition of Polish retainers.

'There,' she said, happily, 'that was all I wanted to know.'

'I don't understand you.'

'It's simple enough. If your highness will allow me to say so, I have known for a long time that you were not the wife of – this gentleman.' Barbe jerked her head in a vaguely contemptuous fashion to indicate Beyle. 'And I was hurt that you did not trust me. It seemed to me I had earned the right to be treated, not as a friend, to be sure, but at least as a loyal servant. I hope your highness will forgive me for having, to some extent, forced the truth from you, but I had to know where I stood and now I am content. I should not care to serve a person of no consequence but I'd regard it as an honour if your highness will allow me to wait on you.'

Marianne began to laugh, relieved and also a little touched, more so perhaps than she cared to admit, by this sudden, unexpected development.

'Oh, my poor Barbe,' she said with a sigh, 'I'd like above all things to keep you with me, but you know my position. I have nothing, I am hunted, threatened with imprisonment—'

'As if that mattered! The great thing is that no great lady can afford to be without an abigail, not even in prison. It is the privilege of those who serve a great house to follow their masters into misfortune. We'll begin with that and maybe the good will follow in its own time.'

'But why choose me? Why not rather go back to your own country?'

Barbe's violet eyes darkened briefly.

'To Janowiec? No, there is nothing for me there any more. No one is waiting for me or wishes to see me again. Besides, for us Poles, France does not seem so very far from home. But most of all, if your highness will allow me to say so, I've taken a fancy to you – and there's no gainsaying that!'

After that, there was nothing more to be said and so it came about that Barbe Kaska came to occupy the place in Marianne's life left vacant by young Agathe Pinsart, much to the disappointment of Henri Beyle who had already been picturing the Polish woman ruling over his own bachelor establishment in the rue Neuve du Luxembourg. But he was not the man to give in to disappointment and nevertheless gallantly offered to pay the new abigail's wages for as long as her mistress remained in his company.

These matters of domestic economy once settled, Barbe set to with a will to assist François in turning her master out creditably. The young man departed for the Kremlin looking distinctly presentable.

Marianne's heart beat high with hope as she watched him go. All the time he was away, she could hardly sit still. While Barbe settled herself by the window with some sewing – she had undertaken to run up a chemise or two for Marianne out of a length of batiste acquired by Beyle out of the products of the sack – singing to herself one of those lugubrious Polish ballads of which she seemed to have an unending repertoire, Marianne paced up and down, hugging her arms across her chest, unable to control her excitement. The hours dragged on, keeping her suspended between hope and foreboding. At one moment, she would be sure of seeing Beyle come back bringing Gracchus and Jolival with him, the next she would be on the brink of tears, convinced that everything had gone wrong and Beyle too had been flung into prison, if not worse. She had suggested to her friend that he should try and speak to Constant who, she was sure, was still her friend.

It was late before Beyle returned. Marianne ran to meet him when she heard his footsteps on the stairs but hope was snuffed out like a candle when she saw his face. He was looking so unhappy that it could only mean bad news.

The news was certainly not good. The Vicomte de Jolival and his servant had not left the Kremlin where, on Napoleon's orders, they had been kept under guard ever since the cardinal's escape.

'They have never left the Kremlin, do you say?' Marianne demanded incredulously. 'Do you mean to tell me the Emperor left them there when he went to Petrovskoi himself? But that's dreadful! They might have been burned to death!'

'I don't think so. Plenty of people stayed there. A good half of the imperial household and all the troops detailed to try and save it from the fire. Napoleon only left in response to the united entreaties of his whole staff who felt they could not guarantee his safety, that was all.'

"Were you able to speak to them?'

'Lord, no! They're closely confined. No one is allowed to communicate with them on any pretext whatever.'

'Did you see Constant? Does anyone know where they are being held? Are they in their rooms or have they been put in prison?'

'I don't know. Even Constant, who sends you his respects, by the way, knows nothing concerning them. When he dared to mention your name to the Emperor, he was told that he had much too great a weakness for the rebellious Princess Sant'Anna, and that if you wanted to know what had become of them, you had only to give yourself up.'

There was a short silence. Then Marianne shrugged despondently.

'Then that is that. He has won. I know what I must do now.'

Instantly, Beyle was between her and the door, barring the way with outstretched arms.

'You are going to give yourself up?'

'I don't see what else I can do. They may be in danger. How do you know the Emperor isn't planning to have them tried and condemned in order to force me to go back?'

'It has not come to that yet. If their fate had been decided, Constant would have known. He would have been told, if only so that he might try and communicate with you. In any case, it will do no good for you to give yourself up. You did not let me finish what I was saying. If you want to secure the release of your friends, you must not only go yourself but also take with you the man whom you helped to escape. Only then will Napoleon forgive you.'

Marianne sat down abruptly on a chair and stared up at him with drowned eyes.

'Then what can I do, my friend? I don't know where to find my godfather even if I wanted to, which I do not. I've no idea whether he went back to St Louis-des-Français—'

'No,' Beyle told her. 'I went there after I left the Kremlin. The Abbé Surugue has not set eyes on him since the day of the fire. He doesn't even know where he might have gone to.'

'To Kuskovo, I expect, to Count Sheremetiev's house.'

'Kuskovo has been burned and our troops are encamped in what remains of it. No, Marianne, you must not look for anything in that direction. In any case, there is nothing you can do that will satisfy the Emperor and your own heart.'

'But I can't just abandon Jolival and Gracchus! The Emperor must be mad to vent his spleen on them. He is so angry with me that he is quite capable of putting them to death!'

She was crying hopelessly, the tears running down her cheeks. She had so much the look of a trapped doe that Beyle, overcome with pity, came and sat by her, putting a brotherly arm round her.

'There, there, my little one, don't cry! You are making a great to-do about nothing, you know. You've a good friend in the Kremlin, for Constant won't betray you, bless him, neither for love nor money. In his opinion, the Emperor has the whole affair out of proportion. I did not tell him where you were to be found, of course, but if there should be any danger he will send word to me at my office and then it will be time enough to consider what to do.'

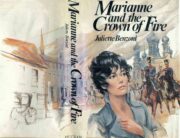

"Marianne and the Crown of Fire" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire" друзьям в соцсетях.