'That is the first thing you should have asked. Where am I? What's happening? What is that noise? That is the sort of thing heroines always say in plays when they come round after a faint. There is some excuse for you, though, because we must have looked very strange to you, so I will put your mind at rest. You are in a room over the stables in the Dolgorouki Palace. The place is left empty for the best part of the time and the porter, who is a friend of ours, let us in. I might go on to puzzle you still further by introducing myself as Mary Stuart and this lady as Dido, but I will rather tell you that I am Madame Bursay, director of the Théàtre Français in Moscow. And I daresay you will feel more honoured by the attentions of your temporary doctor when I tell you that she is none other than that celebrated singer Vania di Lorenzo, of La Scala, Milan—'

'And of the Théâtre des Italiens in Paris! Admirer and personal friend of our great Emperor Napoleon himself!' Dido concluded with a triumphant air.

In spite of the pain in her shoulder and the misery which had returned with the return of consciousness, Marianne could not help smiling.

'You too?' she said. 'I have heard much praise of your voice and talents, Signora. I myself am Princess Sant'Anna and I—'

Before she could finish, Vania di Lorenzo had snatched the candle impetuously out of her friend's hand and was holding it so that its light fell on her face.

'Sant'Anna?' she exclaimed. 'I knew I had seen you somewhere! Princess Sant'Anna you may be but to me you are the singer, Maria Stella, the Emperor's nightingale and the woman who preferred a titled husband to a brilliant career. I know, for I was at the Théàtre Feydeau on the night of your debut. What a voice! What a talent! And what a crime to let it all go!'

The effect of this outburst was almost magical because, notwithstanding Vania's genuine disapproval, it completely broke the ice between the three women by reason of that amazing sense of fellowship which exists between all theatre people under any circumstances, however bizarre.

To Madame Bursay, as to Signora di Lorenzo, Marianne had ceased to be a great lady, or even a lady of quality, she was simply one of their own kind, no more – and certainly no less.

While they made a meal of smoked pork and dried apricots washed down with beer – the diet of the refugees in the Dolgorouki Palace was distinctly unorthodox, being derived almost exclusively from the contents of the palace cellars – the actress and the prima donna explained to their new friend how they came to be there.

Madame Bursay and her company had been holding a dress rehearsal of Schiller's Maria Stuart in the city's Grand Theatre the previous evening and Vania had been trying on the costume in which she was to sing Dido in a few days' time, when the theatre had been invaded by a furious mob. The arrival of the first of the wounded from Borodino and the disastrous news they brought with them had driven the people of Moscow wild with rage. A wave of hatred against the French had arisen and spread like wildfire. The people had turned on everything in the city that had any connection with the hated nation. Shops had been broken into and plundered, private dwellings ravaged and even some French émigrés with no love for Napoleon had suffered.

"We were the best known,' Madame Bursay sighed, 'and the best loved also, until this unhappy day.'

'Unhappy!' Marianne cried. 'When the Emperor is victorious and will soon be in Moscow?'

'I too am a loyal subject of His Majesty,' the tragedienne said, smiling a little, 'but if you had lived through what we did yesterday—It was horrible! At one time we thought we were going to be burned to death in our own theatre. We had barely time to escape by way of the cellars, just as we were, and then we had to wait for nightfall before we could leave our underground refuge. It was impossible to reach our hotel. Lekain, one of our company who was not rehearsing, did manage to get there unobserved and saw our rooms ransacked and all our belongings thrown into the street and burned. And what was worse, while we women were escaping, our stage manager, Domergue, was caught by the mob and nearly torn to pieces. Fortunately, a company of police coming to prevent the theatre from being burned down was able to intervene and he was taken into custody. It seems that Count Rostopchin has announced his intention of sending him to Siberia!'

'Along with his own cook,' Marianne said, sighing. 'It seems to be a passion with him. But what became of the rest of your company?'

Vania made a helpless gesture. 'We don't know. Apart from Louise Fusil and Madame Anthony who are here with us, living across the courtyard, and young Lekain, who has gone out to try and get news, we know nothing of the others' whereabouts. It seemed wiser to separate – being in costume we looked strange enough on our own, but all together! Well, imagine Mary Queen of Scots and all her followers, her guards and ladies in waiting and so forth all walking about the streets of Moscow! We can only hope that they have been as lucky as we are and have found somewhere where they can hide in comparative safety until the Emperor enters Moscow.'

'You took a very great risk in coming out to rescue me,' Marianne said quietly. 'God knows what might have happened to you if you had been seen.'

Vania laughed. 'What was happening in the square was so exciting that we never thought of that,' she said. 'It was like a scene from a play! And we had been so bored. So of course we never hesitated. But in any case I don't believe that there is anyone still living in this part of the city.'

Inevitably, after hearing from the other two, Marianne had to tell something of her own story. She did it as briefly as possible because she was beginning to feel extraordinarily sleepy, as well as slightly feverish from her wound. She dwelt especially on her fears for Jason and her sorrow at having failed to find her friends again. Then, overcome by emotion, she broke down and cried and Vania came and sat on the edge of the sofa and, throwing back the folds of her robe, laid a cool hand on her new friend's brow.

'That's enough of that kind of talk. You are feverish and should rest. When the porter comes up this evening, we will try and persuade him to let us have a better room so that you may have a bed at least. Until then, you must try to forget about your friends because there is nothing you can do to help them. When the French have entered the city – then I expect all those who are in hiding will come out again—'

'If there is still a city at all,' said a cavernous voice from the depths of the room. The two women turned towards it.

'Ah, Lekain! Here you are at last,' Madame Bursay exclaimed. 'What is the news?'

A young man of about thirty, fair-haired with a weak but not unattractive face and graceful in a rather effeminate fashion, stepped out of the shadows. His clothes would have been fashionably elegant but for the dust which covered them and he seemed on the point of exhaustion. His blue eyes rested on the faces of all three women in turn and he summoned up a grin.

'The longer I live abroad, the more I love my own country,' he declaimed, adding in a more ordinary tone: 'Things are going from bad to worse. I don't know if the Emperor will reach Moscow in time to save us. My compliments, Madame,' he went on, turning to Marianne. 'I've no idea who you are but you look as pale as you are beautiful.'

'This is a friend I came upon by chance,' Vania announced. 'Signoria Maria Stella of the Theatre Feydeau. But tell us quickly, young man, what is the latest threat?'

'Give me a drink first. My tongue feels like a dry sponge. It's too big for my mouth.'

'It will be bigger still after a good soaking then,' Madame Bursay retorted but she poured him a full mug of beer which he swallowed down with eyes half-closed and an expression of utter bliss upon his face. Disdaining such trifling matters as good manners, he smacked his lips and bolted down a slice of ham, helping it on its way with a second draught of beer, then threw himself down bodily upon a decrepit armchair which groaned under his weight, and fetched a deep, lugubrious sigh.

'Even when one's body may be doomed to extinction at any minute,' he remarked, 'there is still a great deal of comfort to be found in feeding it.'

'Well, you're a cheerful one, I must say,' Vania scolded him. 'What makes you think we may be doomed to imminent extinction, as you call it?'

The things that are happening in the city. The rumour is spreading that Murat's cavalry is hard on Kutuzov's heels. The civilian population is in full flight.'

'That's no news. They've been fleeing for three days.'

'Maybe, but this is somewhat different. Yesterday it was the rich, the nobility and gentry. Today, it's anyone who has anything to lose. Only beggars, the bedridden and the dying will be left. And by this time all of them are in despair because they are taking away the sacred images from all the churches and monasteries to keep them from falling into the hands of Antichrist and his marauding hordes. Near the church of Peter and Paul I saw the people escorting the wounded to the Lefort Hospital, throw themselves down in the dust at the feet of the priests, stretching out their arms to the icons and pleading for them to remain, crying that the wounded would surely die, and then move on before the priests so much as lifted a hand to ask them, such is the habit of submission among these people. But there is worse to come—'

"What now?' Madame Bursay said irritably. 'Why must you always save everything for dramatic effect, Lekain?'

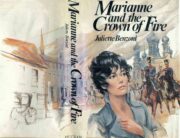

"Marianne and the Crown of Fire" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Crown of Fire" друзьям в соцсетях.