Cesare seemed as though he were finding it difficult to breathe, which meant he was very angry. He took her by the neck, and this time there was more anger than tenderness in the gesture.

“It is time you knew the truth,” he said. “Have you not guessed who our father is?”

She had not thought of possessing a father until Giorgio came into the house, and then, as Vannozza called him husband, she had thought of him as father, but she knew better than to say that Giorgio was their father; so she was silent, hoping Cesare would relax his hold on her neck and let the tenderness return to his fingers.

Cesare had put his face close to hers; he whispered: “Roderigo, Cardinal Borgia, is not our uncle, foolish child; he is our father.”

“Uncle Roderigo?” she said slowly.

“Of a certainty, foolish one.” Now his grip was tender. He laid his lips on her cool cheek and gave her one of those long kisses which disturbed her. “Why should he come here so often, do you think? Why should he love us so? Because he is our father. It is time you knew. Now you will see that it is unworthy to cry for such as Giorgio and Ottaviano. Do you see that now, Lucrezia?”

His eyes were dark again—not with rage perhaps, but with pride because Uncle Roderigo was their father and he was a great Cardinal who, they must pray each day, each night, might one day be Pope and the most powerful man in Rome.

“Yes, Cesare,” she said, for she was afraid of Cesare when he looked like that.

But when she was alone she went into a corner and continued to weep for Giorgio and Ottaviano.

But even Cesare was to discover that the death of those whom he had considered insignificant could make a great difference to his life.

Roderigo, still solicitous for the welfare of his ex-mistress, decided that, since she had lost her husband, she must be provided with another; therefore he arranged a marriage for her with a certain Carlo Canale. This was a good match for Vannozza since Carlo was the chamberlain of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, and a man of some culture; he had encouraged the poet, Angelo Poliziano, in the writing of Orfeo, and had worked with distinction among the humanists of Mantua. Here was a man who could be useful to Roderigo; and Canale was wise enough to know that through Roderigo he might acquire the riches he had so far failed to accumulate.

Roderigo’s notary drew up the marriage contracts and Vannozza prepared to settle down with her new husband.

But as she had gained a husband she was to lose her three eldest children. She accepted this state of affairs philosophically for she knew that Roderigo could not allow their children to remain in her house beyond their childhood; the comparatively humble home of a Roman matron was not the right setting for those who had a brilliant destiny before them.

Thus came the greatest change of all into Lucrezia’s life.

Giovanni was to go to Spain, where he would join his eldest brother, Pedro Luis, and where his father would arrange for honors to fall to him; and those honors should be as great as those which he had given to Pedro Luis. Cesare was to stay in Rome. Later he was to train for a Spanish Bishopric, and to do this he must study canon law at the universities of Perugia and Pisa. For the time being he was with Lucrezia but they were soon to leave their mother’s house for that of a kinswoman of their father’s; therein they would be brought up as fitted their father’s children.

It was a staggering blow to Lucrezia. All that had been home to her for six years would be home no longer. The blow was swift and sudden. The only one who rejoiced in that household on the Piazza Pizzo di Merlo was Giovanni, who strutted about the nursery, wielding an imaginary sword, bowing in mock reverence before Cesare whom he called my lord Bishop. Giovanni, intoxicated with excitement, talked continually of Spain.

Lucrezia watched Cesare, his arms folded across his breast, his face white with suppressed anger. Cesare did not rage, did not cry out that he would kill Giovanni; for once Cesare was beaten.

The first important change of their lives had been reached and they all had to accept the fact that however much they might boast in the nursery, they had no alternative but to obey orders.

Only once, when he was alone with Lucrezia, did Cesare cry out as he thumped his fist on his thighs so violently that Lucrezia was sure he was hurting himself: “Why should he go to Spain? Why should I have to go into the Church? I want to go to Spain. I want to be a Duke and a soldier. Do you think I am not more fitted to conquer and rule than he is? It is because our father loves him better than he loves me that Giovanni has cajoled him into this. I will not endure it. I will not.”

Then he took Lucrezia by the shoulders, and his blazing eyes frightened her.

“I swear to you, little sister, that I shall not rest until I am free … free of my father’s will … free of the will of any who seek to restrain me.”

Lucrezia could only murmur: “You will be free, Cesare. You will always do what you want.”

Then he laughed suddenly and gave her one of those fierce embraces which she knew so well.

She was anxious about Cesare, and that meant that she did not worry so much about her own future as she might otherwise have done.

MONTE GIORDANO

Adriana of the house of Mila was a very ambitious woman. Her father, a nephew of Calixtus III, had come to Italy when his uncle became Pope, because it seemed that under such benign and powerful influence there might be a great future for him. Adriana was therefore related to Roderigo Borgia, who held her in great esteem, for she was a woman not only of beauty but of intelligence. It was owing to these qualities that she had married Ludovico of the noble house of Orsini, and the Orsini was one of the most powerful families in Italy. Adriana had a son who had been named Orsino; this boy was sickly and, having a squint, rather unprepossessing, but on account of his position—as the heir to great wealth—Adriana hoped to make a brilliant marriage for him.

The Orsinis had many palaces in Rome but Adriana and her family lived in that on Monte Giordano, near the Bridge of St. Angelo. And it was to this palace that Lucrezia and Cesare were taken when they said good-bye to their brothers and their mother.

Here life was very different from what it had been in the house on the Piazza Pizzo di Merlo. With Vannozza there had been light-hearted gaiety, and the children had enjoyed great freedom. They had been allowed to wander in the vineyards, or to enjoy trips on the river; they had often visited the Campo di Fiore where it had given them great delight to mingle with all kinds of people. Cesare and Lucrezia realized that life had indeed been changed.

Adriana was awe-inspiring. She was a beautiful woman but always dressed in ceremonial black, insisting constantly that it must not be forgotten that this was a Spanish household even though it was in the heart of Italy. With its great towers and crenellations dominating the Tiber, the palace was gloomy; its thick walls shut out the sunshine and the gaiety of the Rome which the children had known and loved. Adriana never laughed as Vannozza had laughed, and there was nothing warm and loving about her.

She had many priests living in the palace; there were constant prayers, and consequently Lucrezia believed in those first years in the Orsini palace that her foster-mother was a very virtuous woman.

Cesare chafed against the discipline, but even he was unable to do anything about it, even he was overawed by the gloomy palace, the many prayers and the feeling that the palace was a prison in which he and Lucrezia had been incarcerated while Giovanni had been allowed to go in pomp and splendor to Spain and glory.

Cesare brooded silently. He did not rage as he had in his mother’s house; he was sullen and sometimes his quiet anger frightened Lucrezia. Then she would cling to him and beg him not to be sad; she would cover him with kisses and cry out that she loved him best of all … better than anyone else in the whole world, that she would love him today, the next day and forever.

Even this declaration could not appease him, and he remained brooding and unhappy, but sometimes he would turn to her and seize her in one of those fierce embraces which hurt her and excited her. Then he would say: “You and I are together, little sister. We’ll always love each other … best in the world … best in the whole world. Swear it to me.”

And she swore it. Sometimes they would lie together on her bed or his. She would go there to comfort him, or he would come to her for comfort. Then he would talk of Giovanni and how unfair life was. Why did their father love Giovanni? Cesare would demand. Why should not Cesare have been the one who was chosen to go to Spain? Cesare would never go into the Church. He hated the Church, hated it … hated it.

His vehemence frightened her. She crossed herself and reminded him that it was unlucky to talk thus against the Church. The saints, or perhaps the Holy Ghost might be angry and come to punish him. She was afraid, she said; but she said it to give him the chance of comforting her, to remind him that he was great Cesare, afraid of none, and she was little Lucrezia who was the one to be protected.

Sometimes she made him forget his anger against Giovanni. Sometimes they laughed together and remembered the fun they had had on their jaunts to the Campo di Fiore. Then they would swear that no matter what happened they would always love each other best in the world.

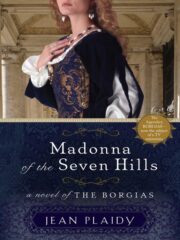

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.