This was the first time that Lucrezia had heard this evil rumor concerning herself, and she shrank from the man who could spread it.

She had never felt so much alone as she did at that time. She longed to have someone like Giulia to confide in, but she never saw Giulia now; Sanchia was too immersed in her own affairs and the battle between Cesare and Giovanni for her favors which she was engendering.

And so there came the day when she signed the document which they had prepared for her, in which she declared that, owing to her husband’s impotence, she was still virgo intacta.

There was laughter in Rome.

A member of the most notorious family in Europe had declared her innocence. It was the best joke that had been heard in the streets for many years.

Even the servants, amongst themselves, could not refrain from sly titters. They had witnessed the passionate rivalry of the brothers for Lucrezia’s affection; they had seen her embraced by the Pope. And there were many who could swear that Giovanni Sforza and Lucrezia had lived as husband and wife.

They did not do so, of course. They had no wish to be taken to some dark dungeon and return minus their tongues. They did not care to risk being set upon one dark night, tied in sacks and thrown into the river. They had no wish to drink of a certain wine and so step into eternity.

But at that time one of the most unhappy people in Rome was Lucrezia. She was filled with shame for what she had done, and she felt that she could no longer endure the daily routine of her life.

She thought longingly of those days of her childhood when she had lived so happily with the nuns of San Sisto, and everything within the convent walls had seemed to offer peace; and, very soon after she had signed that document, she left her palace for the convent of San Sisto.

There she begged to be taken to the Prioress and, when Sister Girolama Pichi came to her, she fell on her knees and cried: “Oh, Sister Girolama, I pray you give me refuge within these quiet walls, for I am sorely oppressed and need the comfort this place has to offer me.”

Sister Girolama, recognizing the Pope’s daughter, embraced her warmly and told her that the convent of San Sisto was her home for as long as she wished it to be so.

Lucrezia asked that she might see her old friends, Sister Cherubina and Sister Speranza, who so long ago, it seemed, had undertaken her religious teaching. The Prioress sent for them and, when Lucrezia saw them, she wept afresh and Sister Girolama told them to take Lucrezia to a cell where she might pray, and that they might stay with her as long as she needed their comfort.

When he discovered that Lucrezia had gone to the convent, Cesare was angry, but the Pope soothed him and begged him not to let any know how concerned they were at this unexpected move.

“If any should know that she had run away from us they would ask the reason,” said the Pope, “and there would be many to question whether she had willingly put her name to our document.”

“They will know soon enough that she has fled to the nuns to seek refuge from us.”

“That must not be. This day I will send men-at-arms to bring her back to us.”

“And if she will not come?”

“Lucrezia will obey my wishes.” The Pope smiled grimly. “Moreover the nuns of San Sisto will not wish to arouse Papal displeasure.”

The men-at-arms were dispatched. Lucrezia was with four of the nuns when she heard them at the gates.

She turned startled eyes to her companions and wished she were one of them, serene and far removed from all trouble. Oh, she thought, what would I not give to change places with Serafina or Cherubina, with Paulina or Speranza?

The Prioress came to her and said: “There are men of the Papal entourage below. They have come to take you back, Madonna Lucrezia.”

“Holy Mother,” said Lucrezia, falling on her knees and burying her face in the voluminous black habit, “I beg you do not let them take me away.”

“My daughter, is it your wish that you should renounce all worldly things and stay here with us all the days of your life?”

Lucrezia’s lovely eyes were full of bewilderment. “They will not permit it, Holy Mother,” she said; “but let me stay awhile. I pray you let me stay. I am afraid of so much outside. Here I find solitude and I can pray as I cannot in my palace. Here in my cell I am alone with God. That is how I feel, and I believe that if you will but give me refuge for a little longer I shall know whether I must give up all outside these walls and become one of you. Holy Mother, I implore you, give me that refuge.”

“We would deny it to none,” said Girolama.

One of the nuns came hurrying to them to report that men were at the gates demanding to see the Prioress. “They are soldiers, Holy Mother. They are heavily armed and look fierce.”

“They have come for me,” said Lucrezia. “Holy Mother, do not let them take me.”

The Prioress went boldly to the gates and faced the soldiers, who told her they were in a hurry, and had come, on the orders of His Holiness, to take Madonna Lucrezia with them.

“She has sought refuge here,” said the Prioress.

“Now listen, Holy Mother, this is an order from the Pope.”

“I regret it. But it is a rule of this house that none who asks for refuge shall be denied it.”

“This is no ordinary visitor. Would you be so foolish as to offend His Holiness? The Borgia Pope and his sons do not love those who oppose them.”

The soldiers meant to be kind; they were warning the Prioress that if she were a wise woman she would heed the Pope’s request. But if Girolama Pichi was not a wise woman she was a brave one.

“You cannot enter my house,” she said. “If you do, you commit an act of profanity.”

The soldiers lowered their eyes; they had no wish to desecrate a holy convent, but at the same time they had their orders.

Girolama faced them unflinching. “Go back to His Holiness,” she said. “Tell him that as long as his daughter craves refuge, I shall give it, even though His Holiness commands me to release her.”

The men-at-arms turned away, abashed by the courage of the woman.

In the Vatican, the Pope and his two sons chafed in quiet anger.

They knew that in the streets it was whispered that Madonna Lucrezia had entered a nunnery, and that the reason was that her family was trying to force her to do something which was against her will.

Alexander came to one of his quick and brilliant decisions.

“We will leave your sister in her convent,” he said, “and make no more attempts to bring her out. They cause gossip and scandal, and until the divorce is completed we wish to avoid that. We will let it be known that Madonna Lucrezia has been sent to San Sisto by ourselves, our wish being that she should live in quiet retirement until she is free of Giovanni Sforza.”

So Lucrezia was left in peace; but meanwhile the Pope and her brothers redoubled their efforts to obtain her divorce.

Life for Lucrezia was now regulated by the bells of San Sisto, and she was happy in the convent where she was treated as a very special guest.

No one brought her news so she did not know that Romans continued to mock at what they called the farce of the divorce. She had never been fully aware of the scandals which had circulated about herself and her family, and she had no notion that verses and epigrams were now being written on the walls.

Alexander went serenely about his daily life, ignoring the insinuations. His one aim was to bring about the divorce as quickly as possible.

He was in constant communication with the convent, but he made no attempt to persuade his daughter to leave her sanctuary. He allowed the rumor, that she intended to take the veil, to persist, realizing that the image of a saintly Lucrezia was the best answer to all the foul things which were being said of her.

He selected a member of his household to take letters to his daughter and, as he was planning that after the divorce he would send her to Spain for a while in the company of her brother the Duke of Gandia, he chose as messenger a young Spaniard who was his favorite chamberlain.

Pedro Caldes was young and handsome and eager to serve the Pope. His Spanish nationality was on his side as Alexander was particularly gracious to Spaniards; his charm of manner was a delight to the Pope, who was anxious that Lucrezia should not become too enamoured of the nuns and their way of life.

“My son,” said Alexander to his handsome chamberlain, “you will take this letter to my daughter and deliver it to her personally. Now that the Prioress knows that my daughter is in the Convent of San Sisto with my consent, you will be admitted to my daughter’s presence.” Alexander smiled charmingly. “You are to be not merely a messenger; I would have you know that. You will talk to my daughter of the glories of your native land. I want you to inspire within her a desire to visit Spain.”

“I will do all in my power, Most Holy Lord.”

“I know you will. Discover whether she is leading the life of a nun. I do not wish my little daughter to live so rigorously. Ask her if she would like me to send a companion to her—some charming girl of her own age. Assure her of my constant love and tell her that she is always in my thoughts. Now go, and when you return come and tell me how you found her.”

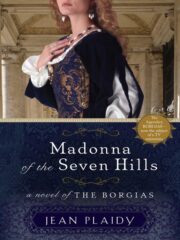

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.