However, on this occasion he determined to try compromise. He gathered together his men but, instead of leaving with them, he wrote to the Pope and explained that his duties in his own dominion prevented his leaving at this time.

He and Lucrezia waited for the command to obey, the expressions of angry reproach.

There was a long silence; then from the Vatican came a soothing reply. His Holiness fully understood Giovanni Sforza’s reasons; he no longer insisted that he should join the Duke of Gandia. At the same time he would like to remind his son-in-law that it was long since he had seen him in Rome, and it would give him the utmost pleasure to embrace Giovanni and Lucrezia once more.

The letter made Lucrezia very happy. “I feared,” she told her husband, “that your refusal to join my brother would have angered my father. But how benevolent he is! He understands, you see.”

“The greater your father’s benevolence, the more I fear him,” growled Giovanni.

“You do not understand him. He loves us. He wishes to have us in Rome.”

“He wishes you to be in Rome. I do not know what he wishes for me.”

And Lucrezia looked at her husband and shivered imperceptibly. There were times when she felt there was no escape from the destiny which her family was preparing for her.

Cesare had rarely been so happy in the whole of his life as he was at this time.

His brother Giovanni was helping to prove all that he, Cesare, had been at such pains to make their father realize. How angry he had been at that ceremony when Giovanni had been invested with the standard, richly embroidered, and the sword, richly jeweled, of Captain General of the Church! How the fury had welled up within him to see his father’s eyes shining with pride as he beheld his favorite son!

“Fool!” Cesare had wanted to cry. “Do you not see that he will bring disgrace on your armies and the name of Borgia?”

And Cesare’s prophecies were coming true. That was what gave him this great pleasure. Now surely his father must see the folly of investing his son Giovanni with military honors which he could not uphold, and the crass stupidity of preventing the brave bold Cesare from taking over the command which, in a fond father’s folly, had been given to Giovanni.

Everything was in Giovanni’s favor. The wealth and might of the Pope was behind him. The great Captain Virginio Orsini was still a prisoner in Naples and could not take part in his family’s defense. To any with an ounce of military knowledge, so reasoned Cesare, the campaign should have been swift and victorious.

And at first it seemed as though it would be so, for, with Virginio a prisoner, the Orsinis appeared to have no heart for the fight, and one by one surrendered to Giovanni’s forces as they had to the French. Castle after castle threw open its gates, and in marched the conqueror without the shedding of one drop of blood.

In the Vatican the Pope rejoiced; even in Cesare’s presence, knowing how galling it was to his eldest son, he could not hide his pride.

That was why the new turn of events was so gratifying to Cesare.

The Orsini clan were not so easily overcome as the brash young Duke of Gandia and his doting father had believed. They had gathered in full force at the family castle of Bracciano under the leadership of the sister of Virginio. Bartolommea Orsini was a brave woman. She had been brought up in a military tradition and she was not going to submit without a fight. In this she was helped by her husband and other members of the family.

Giovanni Borgia was startled to come up against resistance. He had had no experience of war, and his methods of breaking the siege at Bracciano seemed to the experienced warriors on both sides, both childish and foolish. He had no wish to fight, for Giovanni was a soldier who had more affection for jeweled sword and white stick of office than for battle. He therefore sent messages to the defenders of the castle, first wheedling, then threatening, telling them that their wisest plan would be to surrender. It was uncomfortable, camping outside the castle; the weather was bad; and Giovanni’s gorgeous apparel unsuited to it. His most able captain, Guidobaldo of Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino, was badly wounded and forced to retire, which meant that Giovanni had lost his best adviser.

Time passed and Giovanni remained outside the stronghold of Bracciano. He was tired of the war, and he had heard that the whole of Italy was laughing at the Commander of the Pope’s forces, and moreover he guessed how his brother was enjoying this turn of events.

The people of Rome whispered about the grand Captain: “How fares he now? Does he look quite so gorgeous as he did when he set out? The rain and wind will not be good for all that velvet and brocade.”

Alexander was filled with anxiety, and declared he would sell his tiara if necessary to bring the war to a satisfactory conclusion. He could not bear the company of his elder son Cesare, for Cesare did not attempt to hide his delight at the way things were going. This hatred of brother for brother, thought Alexander, was folly of the first order. Had Cesare and Giovanni not yet learned that strength was in unity?

Cesare was with him when the news came to him that Giovanni was still waiting outside the castle and that Urbino had been wounded.

He watched the red blood flood his father’s face and, as he stood there, exulting, Alexander swayed and would have fallen had not Cesare rushed forward to catch him.

Looking at his father, whose face was dark with rich purple blood, the whites of his eyes showing red, and the veins knotted at his temples, Cesare had a sudden terrible fear of a future in which there would be no Alexander to protect his family. Then did he realize how much they owed to this man—this man who hitherto had been renowned for his vitality, this man who surely must possess true genius.

“Father!” cried Cesare aghast. “Oh, my beloved father!”

The Pope opened his eyes and became aware of his son’s anxiety.

“Dear son,” he said. “Fear not. I am with you still.”

Once again that exceptional vitality showed itself. It was as though Alexander refused to accept the ailments of encroaching age.

“Father,” cried Cesare in anguish, “you are not ill? You cannot be ill.”

“Help me to my chair,” said Alexander. “There! That is better. It was a momentary faintness. I felt the blood pounding in my veins, and it seemed that my head would burst with it. It is passing. It was the shock of this news. I must control myself in future. There is no need to fret about that which has not yet happened.”

“You must take greater care, Father,” Cesare warned him.

“Oh my son, my son, do not look so distressed. And yet I feel happy to see that you care so much for me.”

Alexander closed his eyes and lay back in his chair smiling. The astute statesman, always wilfully blind where his family was concerned, allowed himself to believe that it was out of affection for his father that Cesare was alarmed, not because he was aware of the precarious position he, with the rest of his family, would be in if the Pope were no longer there to protect them.

Cesare then begged his father to call his physician, that he might be examined; and this Alexander at length promised he would do. But the Pope’s resilience was amazing and, a few hours after the fainting fit, he was making new plans for Giovanni’s success.

Alas, eventually even Alexander had to face the fact that Giovanni was no soldier, for this became undeniable when help came to the Orsini from the French, and they were able to attack the besiegers of the castle.

Faced with real battle Giovanni proved himself to be a hopeless leader, and the engagement went badly for the Papal forces; the only man among them who distinguished himself was the Duke of Urbino who, recovered from his wounds, was taken prisoner by the Orsini. As for Giovanni, he was wounded, but slightly, and realizing that he was in a somewhat ridiculous position, from which above all things he longed to extricate himself, he declared that being wounded he was unable to carry on, and must leave his armies to finish the conflict under a new commander.

Now the whole of Italy was laughing at the adventures of the Pope’s son. They remembered the ceremony at which he had been made head of the Papal armies; when he had led his armies out of Rome, he had marched like a conqueror.

This was very amusing to the Romans; and many people were pleased. This should teach the Pope that it was dangerous to his own interests to carry nepotism too far.

Cesare had recovered from his alarm over the Pope’s fainting fit, for Alexander was as full of vitality as ever, and Cesare was not going to lose this opportunity of scoring over his brother.

He called his friends to him and together they devised brilliant posters which they set up on various important roads throughout the city.

“Wanted,” ran the words on these posters, “those who have any news concerning a certain army of the Church. Will anyone having such information impart it at once to the Duke of Gandia.”

Giovanni came home, where he was received with undiminished affection by his father, who immediately began making excuses for his son and assuring everyone that, had Giovanni not had the ill luck to be wounded, there would have been a different tale to tell.

And all who heard marvelled at the dissembling of Alexander who so delighted to deceive himself. But they were soon admiring his diplomacy, for it appeared that the Pope never lost a war. Defeated in battle he might be, but terms followed battle, and from these terms the Pope invariably emerged as the victor.

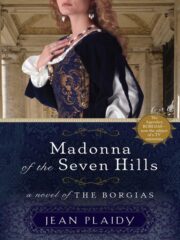

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.