As they rode side by side to the Apostolic Palace, which was to be the Duke’s home, Giovanni could not help taking sly glances at his brother, letting him know that he was fully aware of the enmity which existed between them and that, now he was a great Duke with a son and another child shortly expected, now that he came home at their father’s request to command their father’s forces, he realized that Cesare’s envy was not likely to have abated in the smallest degree.

The Pope could not contain his joy at the sight of his best-loved son.

He embraced him and wept, while Cesare watched, standing apart, clenching his hands and grinding his teeth, saying to himself, Why should it be so? What has he that I lack?

Alexander looking toward Cesare guessed his feelings and, as he knew that Cesare must certainly feel still more angry when he understood in full the glory which was to be Giovanni’s, he stretched out his hand to Cesare and said tenderly: “My two sons! It is rarely nowadays that I know the pleasure of having you both with me at the same time.”

When Cesare ignored the hand, and strolled to the window, Alexander was uneasy. It was the first time Cesare had openly rebuffed him, and that it should have happened in the presence of a third party was doubly disturbing. He decided that the best thing he could do was to ignore the gesture.

Cesare said without turning his head: “There are crowds below. They wait, hoping to catch further glimpses of the splendid Duke of Gandia.”

Giovanni strode to the window; he turned to Cesare, smiling that insolent smile. “They shall not be disappointed,” he said, looking down at his bejeweled garments and back at Cesare. “A pity,” he went on, “that the comparatively somber garments of the Church are all you have to show them, brother.”

“Then you understand,” Cesare answered lightly, “that it is not the Duke whom they applaud, but the Duke’s jeweled doublet.”

Alexander had insinuated himself between them, putting an arm about each.

“You will be interested to meet Goffredo’s wife, my dear Giovanni,” he said.

Giovanni laughed. “I have heard of her. Her fame has traveled even to Spain. Some of my more prudish relatives speak her name in whispers.”

The Pope burst into laughter. “We are more tolerant in Rome, eh, Cesare?”

Giovanni looked at his brother. “I have heard,” he said, “that Sanchia of Aragon is a generous woman. So generous indeed that all she has to bestow cannot be given to one husband.”

“Our Cesare here, he is a fascinating fellow,” said Alexander placatingly.

“I doubt it not,” laughed Giovanni.

Determination was in his eyes. Cesare was looking at him challengingly, and whenever a challenge had been issued by one brother to the other it had always been taken up.

Giovanni Sforza rode toward Pesaro.

How thankful he was to be home. How tired he was of the conflicts raging about him. In Naples he was treated as an alien, which he was; he was suspected of spying for the Milanese, which he had. The last year had brought nothing to enhance his opinion of himself. He was more afraid, and of more people, than he had ever been in his life.

Only behind the hills of Pesaro could he be at peace. He indulged in a pleasant daydream as he rode homeward. It was that he might ride to Rome, take his wife and bring her back with him to Pesaro—defying the Pope and her brother Cesare. He heard himself saying: “She is my wife. Try to take her from me if you dare!”

But they were dreams. As if it were possible to say such things to the Pope and Cesare Borgia! The tolerance which the Pope would display toward one who he would believe had lost his senses, the sneers of Cesare toward one whom he knew to be a coward parading as a brave man—they were more than Giovanni Sforza could endure.

So he could only dream.

He rode slowly along by the Foglia River, in no hurry now that Pesaro was in sight. When he reached home he would find it dreary; life would not be the same as it had been during those months when he had lived there with Lucrezia.

Lucrezia! At first during those months before the marriage had been consummated, she had seemed but a shy bewildered child. But how different he had discovered her to be! He wanted to take her away, make her his completely and gradually purge her of all that she had inherited from her strange family.

He could see the castle—strong, seeming impregnable.

There, he thought, I could live with Lucrezia, happy, secure, all the days of our lives. We should have children and find peace in our stronghold between the mountains and the sea.

His retainers were running out to greet him.

“Our Lord has come home.” He felt grand and important, he the Lord of Pesaro, as he rode forward. Pesaro might have been a great dominion; these few people might have been a multitude.

He accepted the homage, dismounted and entered the palace.

It was a dazzling manifestation of his dream, for she stood there, the sun shining on her golden hair which fell loose about her shoulders, and lighting the few discreet jewels she wore—as became the lady of a minor castle.

“Lucrezia!” he cried.

She smiled that fascinating smile which still held a child-like quality.

“Giovanni,” she answered him, “I was weary of Rome. I came to Pesaro that I might be here to greet you on your return.”

He laid his hands on her shoulders and kissed her forehead, then her cheeks, before he lightly touched her lips with his.

He believed in that moment that the Giovanni Sforza whom he had seen in his dreams might have existence in reality.

But Giovanni Sforza could not believe in his happiness. He must torture himself—and Lucrezia.

He was continually discovering new ornaments in her jewel cases.

“And whence came this trinket?” he would ask.

“My father gave it to me,” would invariably be the answer. Or: “It is a gift from my brother.”

Then Giovanni would throw it back into the box, stalk from the room or regard her with glowering eyes.

“The behavior at the Papal Court is shocking the world!” he declared. “It is worse since the woman from Naples came.”

This made Lucrezia unhappy; she thought of Sanchia and Cesare together, of Goffredo’s delight that his wife should so please his brother, of Alexander’s amusement and her own jealousy.

We are indeed a strange family, she thought.

She would look across the sea, and there was a hope in her eyes, a hope that she might conform with the standards of goodness set up by such men as Savonarola, that she might live quietly with her own husband in their mountain stronghold, that she might curb this desire to be with her own disturbing family.

But although Giovanni had no help to offer her, and only gave her continual reproaches, she was determined to be patient; so she listened quietly to his angry outbursts and only mildly tried to assure him of her innocence. And there were occasions when Giovanni would throw himself at her feet and declare that she was good at heart and he was a brute to upbraid her continually. He could not explain to her that always he saw himself as a poor creature, despised by all, and that the conduct of her family and the rumors concerning them made him seem ever poorer, even more contemptible.

There were times when she thought, I can endure this no longer. Perhaps I will hide myself in a convent. There in the solitude of a cell I might begin to understand myself, to discover a way in which I can escape from all that I know I should.

Yet how could she endure life in a convent? When letters came from her father, her heart would race and her hands tremble as she seized on them. Reading what he had written made her feel as though he were with her, talking to her; and then she realized how happy she was when she was in the heart of her family, and that only then could she be completely content.

She must find a compensation for this overpowering love which she bore toward her family. Was a convent the answer?

Alexander was begging her to return. Her brother Giovanni, he pointed out, was in Rome, even more handsome, more charming than he had been when he went away. Each day he asked about his beloved sister and when she was coming home. Lucrezia must return at once.

She wrote that her husband wished her to remain in Pesaro, where he had certain duties.

The answer to that came promptly.

Her brother Giovanni was about to set out on a military campaign which was to be directed first against the Orsini, and which was calculated later to subdue all the barons who had proved themselves to be helpless against the invader. The rich lands and possessions of these barons would fall into the Pope’s hands. Lucrezia knew that this was the first step on that road along which Alexander had long planned to go.

Now, his dear son-in-law, Giovanni Sforza, could show his mettle and win great honors for himself. Let him collect his forces and join the Duke of Gandia. Lucrezia would not wish to stay on at Pesaro alone, so she must return to Rome where her family would prepare a great welcome for her.

When Giovanni Sforza read this letter he was furious.

“What am I?” he cried. “Nothing but a piece on a chequer-board to be moved this way and that. I will not join the Duke of Gandia. I have my duties here.”

So he stormed and raged before Lucrezia, yet he knew—and she knew also—that he went in fear of the Pope.

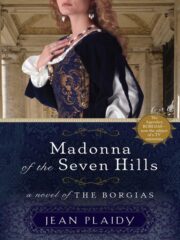

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.