“Then you will be happy, Cesare, for you always hated him.”

“And you … like the rest … worshipped him. He was very handsome, was he not? Our father doted on him—so much that he forces me to go into the Church when that is where Giovanni should go.”

“Come, tell me about your adventures. You were a gay young man, were you not? All the women of Perugia and Pisa were in love with you, and you, by all accounts, were not indifferent to them.”

“There was not one of them with hair as golden as yours, Lucrezia. There was not one of them who knew how to soothe me with sweet words as you do.”

She laid her cheek against his hand. “But that is natural. We understand each other. We were together when we were little. That is why, of all the men I ever saw, there was not one as beautiful in my eyes as my brother Cesare.”

“What about your brother Giovanni?” he cried.

Lucrezia, remembering the old games of coquetry and rivalry, pretended to consider. “Yes, he was very handsome,” she said; then, noticing the dark look returning to Cesare’s face, she added quickly: “At least I always thought so until I compared him to you.”

“If he were here, you would not say that,” accused Cesare.

“I would, I swear I would. He’ll soon be here. Then I’ll show that I love you best.”

“Who knows what gay manners he has picked up in Spain! Doubtless he will be irresistible to the whole world, as he now is to my father.”

“Let us not talk of him, Cesare. So you have heard that I am to have a husband?”

He laid his hands on her shoulders and looked into her face.

He said slowly: “I would rather talk of my brother Giovanni and his beauty and his triumphs than of such a matter.”

Her eyes were wide and their innocence moved him to a tenderness which was unusual with him.

“Do you not like this alliance with the Sforzas?” she asked. “I heard that the King of Aragon is most displeased. Cesare, perhaps if you are against the match and have good reason … Perhaps if you speak to our father …”

He shook his head.

“Little Lucrezia,” he said quietly, “my dearest sister, no matter whom they chose for your husband, I should hate him.”

It was hot June and everywhere throughout the city banners fluttered. The Sforza lion was side by side with the Borgia bull, and every loggia, every roof, as well as the streets, was filled to see the entry into Rome of the bridegroom whom the Pope had chosen for his daughter.

Giovanni Sforza was twenty-six, and a widower who was of a morose nature and a little suspicious of the bargain which was being offered him.

The thirteen-year-old child who was to be his bride meant nothing to him as such. He had heard that she was beautiful, but he was a cold man, not to be tempted by beauty. The advantages of the match might seem obvious to some, but he did not trust the Borgia Pope. The magnificent dowry which had been promised with the girl—thirty-one thousand ducats—was to be withheld until the consummation of the marriage, and the Pope had strictly laid down the injunction that consummation was not to take place yet because Lucrezia was far too young; and should she die childless, the ducats were to go to her brother Giovanni, the Duke of Gandia.

Sforza was no impetuous youth. He would wait, before congratulating himself, to see whether there was anything about which to be congratulated.

He had a natural timidity which might have been due to the fact that he came of a subordinate branch of the Sforzas of Milan; he was the illegitimate son of Costanzo, the Lord of Cotignolo and Pesaro, but he had nevertheless inherited his father’s estate; he was impecunious, and marriage with the wealthy Borgias seemed an excellent prospect; he was ambitious, and that, could he have trusted the intentions of Alexander, would have made him very happy with the match.

But he could not help feeling uneasy when trumpets and bugles heralded his approach as he came through the Porta del Popolo, whither the Cardinals and high dignitaries had sent important members of their retinues to greet him and welcome him to Rome.

In that procession rode two young men, more magnificently, more elegantly attired than any others. They were two of the most strikingly handsome men Sforza had ever seen, and he guessed by their bearing who they must be. He was thankful that he could cut a fine figure on his Barbary horse, in his rich garments and the gold necklaces which had been lent to him for the occasion.

The younger of these men was the Duke of Gandia, recently returned from Spain. He was very handsome indeed, somewhat solemn at the moment because this was a ceremonial occasion and he, having spent some years at a Spanish Court, had the manners of a Spaniard. Yet he could be gay and lighthearted; that much was obvious.

But it was the elder of the men who demanded and held Sforza’s attention. This was Cesare Borgia, Archbishop of Valencia. He had heard stories of this man which made him shudder to recall them. He too was handsome, but his was a brooding beauty. Certainly he was attractive; he would dominate any scene; Sforza was aware that the women in the streets, who watched the procession from loggia and rooftop, would for the most part focus their interest on this man. What was it about him? He was handsomely dressed; so was his brother. His jewels were glittering; but not more so than his brother’s. Was it the manner in which he held himself? Was it a pride which excelled all pride; a certainty that he was a god among men?

Sforza did not care to pursue the subject. He only knew that if he had a suspicion of Alexander he felt even more uneasy regarding his son.

But now the greeting was friendly; the welcome warm.

Through the Campo di Fiore went the cavalcade, the young men in its center—Cesare, Sforza and Giovanni—across the Bridge of St. Angelo to pause before the Palace of Santa Maria in Portico.

Sforza lifted his eyes. There on the loggia, her hair shining like gold in the glittering sunshine, was a young girl in crimson satin decorated with rubies and pearls. She was gripping a pillar of the loggia and the sunlight rested on her hands adazzle with jewels.

She looked down on her brothers and the man who was to be her husband.

She was thirteen and those about her had not succeeded in robbing her of her romantic imaginings. She smiled and lifted her hands in welcome.

Sforza looked at her grimly. Her youthful beauty did not move him. He was conscious of her brothers on either side of him; and he continued to wonder how far he could trust them and the Pope.

The Palace of Santa Maria was in a feverish state of excitement; there was whispering and shouting, the sound of feet running hither and thither; the dressmakers and hairdressers filled the anteroom; Lucrezia’s chaplain had been with her for so long, preparing her spiritually, that those who must prepare her physically were chafing with impatience.

The heat was intense—it was June—and Lucrezia felt crushed by the weight of her wedding gown heavily embroidered with gold thread and decorated with jewels which had cost fifteen thousand ducats. Her golden hair was caught in a net ornamented with glittering precious stones. Adriana and Giulia had personally insisted on painting her face and plucking her eyebrows that she might appear as an elegant lady of fashion.

Lucrezia had never felt so excited in the whole of her life. Her dress may have been too heavy for comfort on this hot day, but she cared little for that, for she delighted in adorning herself.

She was thinking of the ceremony, of the people who would crowd to see her as she crossed from the Palace to the Vatican, of herself, serenely beautiful, the heroine of this splendid occasion, with her pages and slaves to strew garlands of sweetsmelling flowers before her as she walked. She gave scarcely a thought to her bridegroom. Marriage was not, she gathered from what she had seen of those near her, a matter about which one should concern oneself overmuch. Giovanni Sforza seemed old, and he did not smile very often; his eyes did not flash like Cesare’s and Giovanni’s. He was different; he was solemn and looked a little severe. But the marriage was not to be consummated and, Giulia had told her, she need not be bothered with him if she did not want to be. She would continue to stay in Rome—so for Lucrezia marriage meant merely a brilliant pageant with herself as the central figure.

Giulia clapped her hands suddenly and said: “Bring in the slave that Madonna Lucrezia may see her.”

The servants bowed and very shortly a dwarf Negress was standing before Lucrezia. She was resplendent in a gold dress, her hair caught in a jeweled net, and her costume was an exact replica of her dazzlingly beautiful mistress’s. Lucrezia cried out in delight, for this Negress’s black hair and skin made that of Lucrezia seem more fair than ever.

“She will carry your train,” said Adriana. “It will be both amusing and delightful to watch.”

Lucrezia agreed and turning to a table on which was a bowl of sweetmeats, she picked up one of these and slipped it into the Negress’s mouth.

The dark eyes glistened with the affection which most of the servants—and particularly the slaves—had for Madonna Lucrezia.

“Come,” said Adriana sternly, “there is much to do yet. Madalenna, bring the jeweled pomanders.”

As Madalenna made for the door she caught her breath suddenly, for a man had entered, and men should not enter a lady’s chamber when she was being dressed; but the lord Cesare obeyed no rules, no laws but his own.

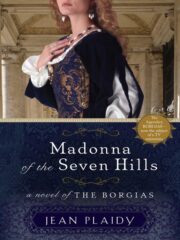

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.