“There’s no greater burden than potential,” the female commenter added.

But as if Calliope heard them, as if she said enough, determination grew in every twist of her muscles, every push of her skates. She nailed an extra jump and earned additional points. Her last two-thirds were solid. It’s not impossible for her to make the Olympic team, but she’ll need a flawless long program tonight.

“I can’t watch.” Andy sets down his corner of my Marie Antoinette dress. “What if she doesn’t medal? In Lola’s costume?”

This has been bothering me, too, but I don’t want to make Andy even more nervous, so I give him a shrug. “Then it won’t be my fault. I only made the outfit. She’s the one who has to skate in it.”

The rest of us abandon my dress as the camera cuts to her coach Petro Petrov, an older gentleman with white hair and a grizzled face. He’s talking with her at the edge of the rink. She’s nodding and nodding and nodding. The cameraman can’t get a good shot of her face, but . . . her costume looks great.

I’m on TV! Sort of!

“You made that in one day?” Norah asks.

Nathan leans over and squeezes my arm. “It’s phenomenal. I’m so proud of you.”

Lindsey grins. “Maybe you should have made my dress.”

We went shopping earlier this week for the dance. I’m the one who found her dress. It’s simple—a flattering cut for her petite figure—and it’s the same shade of red as her Chuck Taylors. She and Charlie have decided to wear their matching shoes.

“You’re going to the dance?” Norah is surprised. “I thought you didn’t date.”

“I don’t,” Lindsey says. “Charlie is merely a friend.”

“A cute friend,” I say. “Whom she hangs out with on a regular basis.”

She smiles. “We’re keeping things casual. My educational agenda comes first.”

The commentators begin rehashing Calliope’s journey. About how it’s a shame someone with such natural talent always chokes. They criticize her constant switching of coaches and make a bold statement about a misguided strive for perfection. We boo the television. I feel sadness for her again, for having to live with such constant criticism. But also admiration, for continuing to strive. No wonder she’s built such a hard shell.

I’m yearning for the network to show her family, which they didn’t do AT ALL during the short program. Shouldn’t a twin be notable? I called him yesterday, because he’s still too shy to call me. He was understandably stressed, but I got him laughing. And then he was the one who encouraged me to invite Norah today.

“She’s family,” he said. “You should show encouragement whenever you can. People try harder when they know that someone cares about them.”

“Cricket Bell.” I smiled into my phone. “How did you get so wise?”

He laughed again. “Many, many hours of familial observation.”

As if the cameramen heard me . . . HIM. It’s him! Cricket is wearing a gray woolen coat with a striped scarf wrapped loosely around his neck. His hair is dusted with snow and his cheeks are pink; he must have just arrived at the arena. He is winter personified. He’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

The camera cuts to Calliope, and I have to bite my tongue to keep from shouting at the television to go back to Cricket. Petro takes ones of Calliope’s clenched hands, shakes it gently, and then she glides onto the ice to the roar of thousands of spectators, cheering and waving banners. Everyone in my living room holds their breath as we wait for the first clear shot of her expression.

“And would you look at that,” the male commentator says. “Calliope Bell is here to fight!”

It’s in the fierceness of her eyes and the strength of her posture as she waits for her music to begin. Her skin is pale, her lips are red, and her dark hair is pulled into a sleek twist. She’s stunning and ferocious. The music starts, and she melts into the romance of it, and she is the song. Calliope is Juliet.

“Opening with a triple lutz/double toe,” the female says. “She fell on this at World’s last year . . .”

She lands it.

“And the triple salchow . . . watch how she leans, let’s see if she can get enough height to finish the rotation . . .”

She lands it.

The commentators drift into a mesmerized hush. Calliope isn’t just landing the jumps, she’s performing them. Her body ripples with intensity and emotion. I imagine young girls across America dreaming of becoming her someday like I once did. A gorgeous spiral sequence leads into a dazzling combination spin. And soon Calliope is punching her arms in triumph, and it’s over.

A flawless long program.

The camera pans across the celebrating crowd. It cuts to her family. The Bell parents are hugging and laughing and crying. And beside them, Calliope’s crazy-haired twin is whooping at the top of his lungs. My heart sings. The camera returns to Calliope, who hollers and fist-pumps the air.

No! Go back to her brother!

The commentators laugh. “Exquisite,” the man says. “Her positions, her extensions. There’s no one like Calliope Bell when she’s on fire.”

“Yes, but will this be enough to overcome her disastrous short program?”

“Well, the curse remains,” he replies. “She couldn’t pull off two clean programs, but talk about redemption. Calliope can hold her head high. This was the best performance of her career.”

She puts on her skate guards and walks to the kiss-and-cry, the appropriately nicknamed area where scores are announced. People are throwing flowers and teddy bears, and she high-fives several people’s hands. Petro puts his arm around her shoulders, and they laugh happily and nervously as they wait for her scores.

They’re announced, and Calliope’s eyes grow as large as saucers.

Calliope Bell is in second place.

And she’s ecstatic to be there.

chapter thirty-three

The wig comes on, and I’m . . . almost happy.

There’s something wrong with my reflection.

It’s not my costume, which would make Marie Antoinette proud. The pale blue gown is girly and outrageous and gigantic. There are skirts and overskirts, ribbons and trim, beads and lace. The bodice is lovely, and the stays fit snugly underneath, giving me a flattering figure—the correct body parts are either more slender or more round. My neck is draped in a crystalline necklace like diamonds, and my ears in shimmery earrings like chandeliers. I sparkle with reflected light.

Is it the makeup?

I’m wearing white face powder, red blush, and clear red lip gloss. Marie Antoinette didn’t have mascara, so I felt compelled to cheat there. I’ve brushed on quite a bit over a pair of false eyelashes. My gaze travels upward. The white wig towers at two feet tall, and it’s adorned with blue ribbons and pink roses and pink feathers and a single blue songbird. It’s beautiful. A work of art. I spent a really long time making it.

And . . . it’s not right.

“I don’t see me,” I say. “I’m gone.”

Andy is unlacing my buckled platform combat boots, preparing to help me step inside of them. He gestures in a wide circle. “What do you mean? ALL I can see is you.”

“No.” I swallow. “There’s too much Marie, not enough Lola.”

His brow furrows. “I thought that was the point.”

“I thought so, too, but . . . I’m lost. I’m hidden. I look like a Halloween costume.”

“When don’t you look like a Halloween costume?”

“Dad! I’m serious.” My panic rapidly intensifies. “I can’t go to the dance like this, it’s too much. Way too much.”

“Honey,” he shouts to Nathan. “You’d better get in here. Lola is using new words.”

Nathan appears in my doorway, and he grins when he sees me.

“Our daughter said”—Andy pauses for dramatic effect—“it’s too much.”

They burst into laughter.

“IT’S NOT FUNNY.” And then I gasp. My stays crush my rib cage, making the outburst labored and painful.

“Whoa.” Nathan is suddenly beside me, his hand on my back. “Breathe. Breathe.”

I was already nervous about going to the dance and seeing my classmates. At least I won’t be alone—I’m meeting Lindsey and Charlie there—but I can’t go like this. It’d be humiliating. I need Lindsey here; she’d take control. But she’s in the middle of a murder-mystery dinner party, and Charlie has wagered a month of school lunches that he’ll solve the mystery before she does. It’s important to Lindsey that she wins.

“Phone,” I pant. “Give me my phone.”

Andy hands it to me, and I dial Cricket instead. I’m sent directly to his voice mail, like I have been all afternoon. He called this morning to make sure I was going to the dance, but we haven’t talked since. I keep fantasizing that we can’t get in touch because he’s on an airplane, planning to surprise me by magically appearing at my school during the first slow song, but it’s most likely a snowstorm wreaking havoc with his connection. Tonight is the Exhibition of Champions, and Calliope is performing in it. He has to be there.

But tomorrow . . . he’ll be home.

The thought temporarily calms me. And then I see my reflection again, and I realize that tomorrow helps nothing about tonight.

“O-kaaaay.” Andy pries the phone from my death grip. “We need a plan.”

“I have a plan.” I tear at the pins holding the wig to my head. “I’ll take it apart. I’ll do a modern reinterpretation of it in my own hair.” I’m flinging the pins to the floor like darts, and my parents step back nervously.

“That sounds . . .” Nathan says.

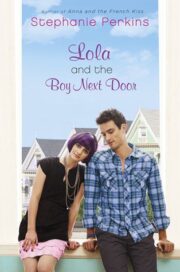

"Lola and the Boy Next Door" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lola and the Boy Next Door". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lola and the Boy Next Door" друзьям в соцсетях.