A million and one apologies for not writing more before! You were probably worried sick when you got nothing but that hospital postcard I sent, but I wasn’t in shape to write much. I am feeling heaps better now and thought you deserved more of an explanation.

I was working a route that went to a poste near the rear trench. Close enough to “smell hell,” as they say. Due to the heavy shelling, the blessés hadn’t yet been brought to this particular poste, so I stayed in the dugout, waiting. Pretty soon I saw the brancardiers struggling up over the ridge above the dugout. This rise is a bit chancy, as it is fully in view of the Boche guns. It was a moonlit night, and there was a brief moment when the brancardiers and stretcher were illuminated at the top of the ridge. Long enough for a gunner to open fire.

I saw the stretcher fall and so I ran up the hill. One of the brancardiers was down, but the blessé seemed to be okay. I pulled the wounded brancardier down the hill a ways and then helped the other guy with the stretcher. We were fired upon again. A shell hit quite close, enough to get me with some fragments in the shoulder and right foot. We somehow managed to get the blessé, the wounded brancardier, and me into the ambulance, though I was in no shape to drive.

My wounds weren’t too serious, but I got an infection and was quite feverish. I was moved farther back, until I ended up here in Paris. I’m so sorry, Sue. I know you must’ve been worried when you got that postcard saying I was in the hospital. I was in no condition to write. The French doctors put tubes in the wound to drain off infection, and I couldn’t move my arm for a few weeks. And none of my nurses spoke a word of English, so I couldn’t even dictate a letter. My shoulder is still rather sore and I’m writing this in brief stages. In my fevered dreams, though, you were always there, sitting next to me.

P.S. Please, please, please send some books! I’m not sure how much longer I’ll be in the hospital, but I am near to climbing the walls for lack of anything interesting to read.

Hôtel République, Paris, France

May 6, 1916

My dear, funny girl! When I asked for books, I intended for you to just pop them in the mail. Although Louisa May Alcott? You did grab whatever was on hand as you ran out the door. What I can’t figure out, though, is how you could make it through a ten-plus-hour train ride with nothing aside from Jo’s Boys to read. But, really, Sue, that’s what you get for dashing out of the house with absolutely no suitcase! Not even a clean pair of socks. Good thing I lent you a pair of mine. I know you’ll give them back someday.

You’re always in my thoughts, but to see you again in person, drink you up like the sweetest medicine in the whole hospital—I feel like a new man. The doctors and nurses might as well have been peddling barley water for all it compared to you. My own personal tonic.

I’ll be heading back to Place Three tomorrow. Will write more then. I just wanted there to be a letter waiting for you when you got home.

Somewhere in the channel

6 May 1916

Davey, Davey. You didn’t have to get yourself shot in order to get my attention! You know that I love you regardless. It was a very sneaky ploy to get me onto a boat, though. If I hadn’t seen evidence to the contrary with my own eyes, I never would’ve believed you were as sick as you suggested.

You looked quite pathetic, dear, stretched out on that hospital cot, that you had me in a grip of worry when I first spotted you! So thin and pale under that sheet, your curls limp on the pillow—I about burst into tears. But then you opened those eyes, the color of the hills, and said, “There you are,” as if you’d been expecting me, and I knew you were fine. I’m surprised they discharged you so quickly, but perhaps they wanted to get rid of you after so long. Though after the comments you kept whispering in my blushing ear, I’m not surprised. The nurses are nuns, Davey. You’re lucky they didn’t speak a word of English.

Not that we needed words once in that hotel room. Your kisses very effectively stopped mine, the way they did in London. Very effectively. I wouldn’t have wished any of that long, tangled night away for an instant, but, my dearest, if I had known how much pain you would be in the next morning, I might have hesitated. Or, at the very least, bought a second bottle of brandy.

Oh, I wish we could’ve had more than that night! I wish we could have hidden in that room as long as the last time. Nine days to kiss, eat oranges, have good intentions of sleeping. But I know you had to go check in. I know you had to head back out to that ambulance of yours. To let you go again only half a day after catching you back in my arms—oh, Davey, it was impossibly hard. But you’re right. I worry so much about our “tomorrow,” about each and every goodbye, that I don’t enjoy the “right now.”

There’s enough to worry about in the future. I have no idea what tomorrow will tell about Iain. I have no idea what tomorrow will tell about anything. But you sat on that bed, bare-chested and beautiful and here. Davey, you are my “right now.”

At a time when I feel so uncertain, I was reassured by your confidence. I think seeing you, though, was the only tonic I needed. It cleared away any doubts and worries.

I should get back up to Skye in a few days. I’ll go straight through this time, not stopping in Edinburgh. I’ll write more once I get home. I just wanted there to be a letter waiting for you at Place Three.

Place Three

May 9, 1916

Sue,

Back at Place Three. Found your other letters waiting for me, the ones from the 12th, 22nd, and 25th. Were you really so worried? I’m touched, actually. I should get myself wounded more often. Not only did it work rather well at getting you to forgive me and getting you to admit how much you adore me, but I got the added bonus of seeing your beautiful face once more. And, once you got me out of that bleak hospital, there was the added, added bonus, which (to be perfectly honest) probably did my poor battered body more harm than good but left my mind in an oh-so-blissful state.

I’m still not quite up to par, but I’m doing better. They’ve offered me a citation for my actions. More important (at least in our section) is that I’ve finally earned my nickname! These nicknames are very important among us, as they signify that you’ve “proven” yourself and are truly part of the bunch. I’ve already told you about Pliny and Riggles. Harry already has his nickname—can you believe his real name is Harrington? Among the squad, we also have Lump, Jersey, Skeeter, Gadget, Bucky, and Wart. Don’t ask where they all came from, as I’m not sure I could even tell you! I’ve been christened Rabbit. The guys say I’m so lucky with these scrapes of mine, it’s as if I have a lucky rabbit’s foot. Not my right foot, of course, but my left foot came out okay, and isn’t that the lucky one, anyhow?

Isle of Skye

15 May 1916

Davey,

You are not to get yourself wounded again! Not so much as a sliver in your toe. Do you hear me? If you do, I shan’t come down again. I’ll toss every letter you send into the grate and ignore your boyish cries for attention.

You didn’t tell me: Is it part of your job to hike up dangerous parapets to fetch stretchers? All this time, I consoled myself with thinking you were safe, playing chauffeur well behind the lines. And now you say that you are not only driving right up to the danger zone but getting out of your vehicle! Please promise me you won’t do that again.

I did finally get the postcard you sent when you first arrived in hospital. Doesn’t say much for the mail service that it got here almost a month after you sent it. If I had received that card when I was intended to get it, I would’ve been to see you even sooner. Curse the General Post Office!

I arrived back here on Skye to find that my new cottage is finished. It probably won’t look like much to you, but to me it is a palace. Two storeys, a wooden floor, a chimney on each end of the house, windows with glass, and a door that latches! Such luxuries, I tell you. Here’s a wee sketch of the new place.

Finlay has been helping over there, working on the building. Since getting his prosthetic leg, he’s gradually been able to find a small measure of peace. Da found some thick pieces of driftwood and Finlay fitted them together in a mantel for my sitting room. He then carved the mantel all the way around with mermaids and selkies and sprites. It is truly the mantel of an island girl. It is the mantel of a girl who has conquered the sea by conquering her fears.

Poor Finlay, though, has been rather melancholy. Iain is not the only one he mourns. Things have been going sour with his girl, Kate. Since he returned, she’s been coming by less and less. Finlay’s still holding out hope that she’ll come back to him, get used to his leg, the way he’s had to. But I’m not so sure. Nearly every time I go to the post office, I see her, and with perfume-soaked envelopes. I can’t bring myself to tell Finlay. He’d just crumble, Davey.

I am on my way back to my own croft, to start moving things into the cottage. I know the bedding needs a hearty washing and the mattress an airing. Everything else could probably use a good scrubbing as well before I put it away in the clean new cottage. I’ll post this on my walk over there.

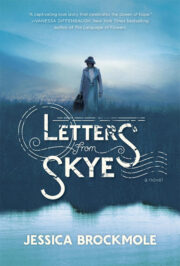

"Letters from Skye" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Letters from Skye". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Letters from Skye" друзьям в соцсетях.