Stephen fought back an ironic smile. “How strange. What sort of money?”

“Gold, of course. He knew better than to offer bank drafts, at least.”

“Or he didn’t have them,” said Stephen. Ward had been not quite penniless when he’d escaped, but he’d spent some time in America learning magic. Stephen had never heard that turning lead into gold was actually possible, but spiriting money out of a bank vault or jewels out of a bedroom would certainly be within the power of most magicians. “Anything else?”

Green smiled now, his eyes dancing. “Well,” he said, drawing out the word while Stephen waited and tried not to glare, “I did have him followed, of course. After he left with his new toy. He went to an office building—give me a moment.” He pulled a silver rope and summoned the butler. “Bring me the book in the top right drawer of my desk.”

“An office building?” Stephen asked when the butler had vanished. “He can’t live there. People would talk.”

“I very much doubt that he does. He came out again an hour later—but so did the sun, and my servant doesn’t do well in the full light of noon. I thought I’d spent quite enough time on the man in any case. He’s unbalanced, he lacks perspective, and he’ll die on his own in a few years. Ah.”

The butler came back and handed Green a small leather-bound ledger, then vanished.

“He has wonderful conversation,” said Green, flicking through the pages, “if only you get to know him. Or so I’d imagine. Thirty-Nine Brick Lane is the building you’re looking for. Consider this a gesture of goodwill on my part.”

“I’ll try,” said Stephen.

Twenty-nine

“What are you doing?”

Colin’s voice came suddenly and without prelude from the previously empty room. Up on a stepladder, her arms full of books, Mina twitched but didn’t jump or scream. “Cataloguing the library,” she said, rather than any of the sarcastic replies that came to mind.

She plucked a final volume from the shelves. It was bound in green leather and newer than some of the others, but the dust was equally thick. Mina held back a sneeze and climbed carefully down the ladder.

“Give over a few of those, will you?” Colin held out his hands, and Mina was glad enough to fill them. When he felt the dust, she didn’t even try not to giggle at the expression on his face. “Good Lord. How long have we had these? And what have we been doing with them?”

“A long time and not much, from what I can tell,” Mina said. She deposited the rest of her stack onto the desk with a solid thump.

“And Stephen still has you messing about with them? He has grown into a tyrant.”

“He’s done no such thing,” said Mina, sharply enough to make Colin widen his eyes and hold up his hands in mock defense. “And he didn’t give me the job. He hasn’t had me do any work, really.”

Colin eyed her as if she were some newly discovered form of life. “You mean to say you volunteered? Why on earth?”

“Because it needs doing, and I needed something to do.”

“Ah.” The new species was a little more comprehensible, it seemed, alien as it might be. Colin looked from Mina to the desk. “And you’ve been doing this all day?”

“More or less.”

Less was more accurate, despite Mina’s best intentions on the subject. Half her records had had blots, misspellings, or other features that had meant she’d had to cross them out and write them again. She’d written down one book twice and completely forgotten about another until she’d found it by the windowsill. Every trip up and down the ladder had taken about twice as long as normal, too.

Mina could have laid some of the blame at Colin’s feet. Their earlier conversation had left her thinking about mortality and humanity, rules and consequences, and coming to no useful conclusion regarding any of it. She wasn’t cut out for philosophy, she’d told herself, but her efforts to direct her thoughts elsewhere had only sent them toward that entry in not-Saint George’s journal, the one about rites and children, at which point she’d inadvertently knocked a set of Johnson’s works to the floor.

Work usually distracted her from troubling thoughts, not the other way around. What was wrong with her?

“Then I’m right in thinking it’s not a very urgent matter,” Colin said. “And that means you can come out with me.”

Coming back from her thoughts, Mina blinked at him. “Out? Where? Why?”

“Out.” He leaned against a bookshelf, counting off the points on his fingers. “Anywhere you want, within reasonable limits. Because London is quite a bit more entertaining than the inside of this library or even, if I may dare to say it, the inside of this house.”

“Yes, but why me?”

“Because you’re—” He looked at Mina’s face, saw the skeptical expression she’d used on dozens of other young men, and grinned ruefully before switching to honesty. “You’re here, and you’re pleasant enough company. And I don’t know many people in the city these days, or at least not many people who’d be glad to see me turn up, looking as I do.”

If he felt any sorrow about the matter, he concealed it easily enough—much easier than Stephen would have, Mina thought. Still, she felt a little sympathy for him, and more so because he’d had sense enough not to try and charm her. “I can’t,” she said.

“Of course you can. You don’t turn to dust in the sunlight. My brother would have mentioned.”

“I agreed,” she said, “not to go out of the house without Stephen, not until this matter with Ward is settled.”

“Oh, that’s the letter of the agreement, true enough.” Colin waved a hand. “But the spirit of it is that you shouldn’t tell anything to Ward or his men, whether you mean to or no. Stephen’s presence was meant to secure as much, and so mine should do just as well. I’d hardly risk his safety or let that jumped-up fellow Ward get his hands on anything important.”

“Well—”

“I’ll give you my word on it.”

“And what if they try something when we’re not here?”

“In broad daylight? This is a respectable neighborhood, or so I hear. Besides, Stephen told me that both of you have been out of the house before this, and no harm came of it.” Colin smiled at her. “So, you see, he trusts me, which means you should too.”

“Does it really?” Mina asked.

“Unless you’re more concerned for his welfare than he is. And if my intentions are evil, the farther I am from the house, the safer we all are, aren’t we? Particularly if you have me out in a public place somewhere. I’ve not been known to do horrible things in public. Mostly.”

There was a certain logic in his argument, self-serving as it was—and then, he’d never pretended that it was anything else. Like his brother, Mina sensed, Colin would never tell her that what he was doing was for her own good. As with Stephen, it was a refreshing change.

Being sought for her company was flattering, too, even if it was because she was the only remotely appropriate person around. If Colin thought she was a proper companion to take out into society—but no, it was best not to find that too encouraging. Colin wasn’t anything like proper. He’d already said he wasn’t particularly human in his outlook, and he’d also said that he and Stephen were very different people.

Flattery, without further implications, would still be enough. And getting out of the house would do Mina good. Given how quickly her thoughts had turned to Stephen, some distraction was certainly the best thing for her.

“Anywhere I want?” she asked.

“Within reasonable limits. I don’t think it would be a terribly grand idea for us to wander over to Spain, for instance, and I’ll not go to any sort of improving lecture, as my sense of chivalry only extends so far. Otherwise,” he said and gave a ludicrously courtly bow, “I am at your service.”

A page of the Times popped into Mina’s head. She’d read the article over breakfast and peered as hard as she could at the few small pictures that went with it.

“There’s an exhibition at the British Museum,” she said. “Art from India. Some of it’s thousands of years old—which might be less impressive for you, I suppose,” she added, “but there are some really wonderful paintings, they say, and some statues that—”

“Art,” said Colin, laughing and sighing at the same time. “Ancient art. I should have known.”

“Should have known what?”

“It’s as bad as taking Stephen out on the town.”

“Well, if you don’t want to—”

“No, no, I did promise. And I’ll enjoy myself, too. I’m not a complete Philistine. See, you’ll be having a good influence on me.”

“I doubt any woman can say that,” said Mina. “Give me a few minutes to change my dress, will you?”

“I wouldn’t have been rude enough to suggest it, but I do think it’d be a good idea. You’ve most of a book cover on your collar, too,” said Colin.

“Thank you.” Mina plucked the scrap of desiccated leather off her blouse and headed up to her room.

Her wardrobe was such as to spare her any moment of indecision. After washing her face and hands, she put on her best dress, the violet cotton she wore when she dressed for dinner. At least it would be more appropriate for the museum. Mina brushed her hair quickly, put it up again, then pinned on her best hat and peered into the small mirror.

Allowing herself a moment of vanity, she admitted that she looked rather nice. More to the point, she looked respectable. Respectability was really what mattered on this excursion, but despite the dreams and the case of nerves she’d been carrying around all day, her eyes were bright and her cheeks were flushed. Before she pulled the self-indulgent part of her mind up sharply, she thought that it was a pity nobody would be around to notice.

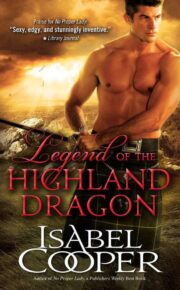

"Legend Of The Highland Dragon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Legend Of The Highland Dragon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Legend Of The Highland Dragon" друзьям в соцсетях.