To Lara’s surprise the eyes in the face opened, and Llyr observed her closely. “She is very beautiful, but astoundingly ignorant,” Llyr pronounced.

“Your staff talks!” Lara exclaimed.

“You state the obvious,” Llyr replied. “Why would I not speak? I have eyes to observe, and a mouth, not to mention a lean half body. I need no more than that.”

“I beg your pardon,” Lara said. “I have never seen anyone like you.”

“She has manners, and that will count for something,” Llyr murmured to Master Bashkar. “Now, let us see how much she knows. Precious little, I can tell already.”

“Please sit down,” Lara invited the old man.

“Do not mind Llyr, my child,” Master Bashkar said. “He does have a tendency to speak his mind. He comes from an ash tree, and they are very frank, unlike the oaks and the maples. As for the aspen and birch, they hardly speak above a whisper.”

“Oaks are dour, and maples chatter too much,” Llyr observed.

“And the palms like those at the village oasis?” Lara asked.

“Palms are incredibly flighty creatures,” Llyr said disapprovingly.

“Enough talk about your relations,” Master Bashkar said sternly.

“I am certainly not related to a palm,” Llyr snapped, and then his eyes closed.

Lara could not help but giggle.

The old man smiled and said, “Now, child, I must find out what you know.”

For the rest of the day he sat with her, asking questions, nodding and tching. Noss brought them food at one point, gasping in surprise when Llyr demanded cheese and a mug of ale. His carved arms reached out from the staff to take the mug Noss brought. As the shadows began to lengthen over the valley, Master Bashkar finally arose.

“We have much work ahead of us, my child, and I do not know yet how much time we will have together, but never fear. We will manage. I will be back tomorrow morning at the ninth hour.” He bowed to her, and departed.

“He seems a kind old man,” Noss noted after Master Bashkar had gone.

“And wise. You must sit with me and listen so you may learn, too, Noss. Can you read or write at all?” Lara asked her.

“What use would I have for reading or writing?” Noss replied.

“Each skill you acquire makes you more valuable to your mistress,” Lara told her.

“Will you teach me?” Noss said.

“I will. We’ll start tomorrow before Master Bashkar comes,” Lara promised.

The prince came to join her, and they ate their supper in the garden. Afterwards, he made love to her, laying her upon her bed naked, and spending almost an hour just stroking and kissing her body. He rubbed her with sweet oils until her skin tingled. Then he gave her the flask of oil, and told her to rub him. Her blood grew hotter with each stroke of her palms upon his bronzed flesh, but she suddenly realized that she appreciated the subtlety of the fragrant caresses. Their joining would be thunderous, and it was. She shuddered with pure desire as he slowly slipped his manroot into her body, sighing as Kaliq pushed deep. His mouth found hers, one kiss following another until it seemed as if their kisses had neither beginning nor end. She trembled, and he withdrew slightly, to her protest.

“Nay, my love,” he told her. “You must learn to control your hunger, for only then can you control your lover.”

“I don’t want to control you,” she gasped. “I just want pleasure!”

His laughter was soft. He kissed her lips again in a tender embrace. “One day there will be a man you need to control, must control, else he destroy you. So now you practice on me, and on the other lovers you will have in your travels, Lara. You must grow stronger with the pleasure, not weaker.”

“Just this once!” she pleaded.

“No,” he said. “Now make me desire you more than you desire me, my love. Tighten the muscles of your sheath to embrace my manroot, and hold it captive so it cannot release its juices until you are ready for them. Ahhh! That’s it!”

She followed his instructions, and squeezed him hard. He groaned aloud, praising her. Lara was very surprised for she had never considered that a woman could dominate a man in such a fashion. Fascinated, she played with him for some time until he was begging her for the pleasure that fulfillment gave their bodies. “Now!” she ground out into his ear, her nails digging into his shoulders. “Now, my lord!” And she wrapped her legs about him, closed her eyes, and let the pleasure overtake their bodies.

“You are incredible, and a wonderful student,” he told her afterwards, and when he had recovered himself he arose from her bed. “Sleep now, my love. I will see you on the morrow.”

“Wait!” Lara cried, raising herself on an elbow. “What of Maeve?”

“I have sent the message. Now we must wait, and see if she will come,” he said.

“What if she does not, my lord Kaliq?” Lara asked.

“Then she does not,” he answered, “but she will. You are her only grandchild. Your mother must have loved your father very much to refuse to spawn other offspring.”

“Then why did she leave us?” Lara demanded.

“You must ask her,” Kaliq said, and then he left her.

In the weeks that followed Lara never left the palace. The village in the Desert below was almost forgotten. She studied each day with Master Bashkar, Noss by her side learning at her own pace. Each morning before the old man came she instructed Noss in her letters, and then her writing, and finally she taught her how to read. Noss was surprisingly quick. For Lara, however, learning the history of Hetar was fascinating.

She learned that there was a High Council of eight that met in the City most of the year. Two members came from the Forest, two from the Coastal Region, two from the Desert and two from the Midlands, of which the City was considered a part. The council had a single overlord. The ruler of each of the provinces would take a turn as council head, rotating every three moon cycles, and only voting to break a tied vote. It was the High Council’s duty to govern Hetar, to see that its laws were upheld, to make new laws, and to keep the Outlanders at bay and contained within their borders. The council worked with the guild heads to see that their civilization continued to run smoothly. She had lived in the City most of her life, yet she had never known of the High Council. “Why?” she asked Master Bashkar.

“Are there places of learning in the City or throughout the provinces, my child?” he asked her.

“For the wealthy, aye, but not for the ordinary people,” Lara said. “What little I learned, I learned from my grandmother, who learned it from I know not where.”

“It is not necessary to educate a people if you keep them content,” Master Bashkar said quietly. “Give them a roof over their heads, enough sustenance to keep them from starving, free public entertainments, perhaps a small reason for living and you do not have to educate them. It was not always so on Hetar.

“Once all children were educated to their full potential in order that they might advance themselves if they chose, and be of use to our society. But that led to dissension as people began to think for themselves, and question their leaders. Those in power do not like being questioned. As those wise ones who instructed the young grew old and unable to teach, others took their places. But they did not teach as well, nor did they teach our history, or our great books and poetry. Mathematics became complex and convoluted. The ordinary folk could not understand it, but no one taught them the simplicities of mathematical skills, or logic. But they were kept fed, housed and entertained, and were encouraged to use their skills at whatever could bring them in a few coins. Education was no longer encouraged, and so finally it was no longer offered to the people.”

“What is poetry?” Lara asked him.

“A story in rhyme,” he told her. “I am sure you have heard street poetry, Lara, but it is unlikely you have ever heard the great sagas and songs of old that were once taught, and recited about the halls at night.”

“No,” she said. “I have never heard anything like that.”

“Nor I,” Noss chimed into the conversation.

“There is a great saga that was once told of how the Shadow Princes of the Desert came into being eons ago,” Master Bashkar said.

“Prince Kaliq once told me he had a Peri ancestor, but he also said his kind had come from the shadows at the beginning of time,” Lara said. “How can that be?”

“Before time as we now know it began,” Master Bashkar said, “Hetar was a world of clouds and fog. The Shadow Princes came first from those mists. They were male spirits, and for several generations they mated with the faerie races they found here. Then the clouds cleared away, and the beauty of the planet was visible to all. At that time it was discovered there were others on Hetar as well. The Forest Lords descended from tree spirits and banded with the Midland folk who came from the earth spirits. The people from the Coastal Region had their origins in the sea. They built the City at the center of it all, and became civilized.”

“But what of the Shadow Princes?” Lara asked.

“The faerie women they had mated with bore only sons. Discovering this hidden valley, they chose the Desert as their realm,” Master Bashkar continued. “But soon it was feared there would not be room for all the offspring they were producing, for they were a fertile race. It was then the princes decided if the faeries would grant them long life and the same ability to reproduce only when they chose, they would remain in the Desert, joining the High Council as a part of Hetar, keeping clear of all dissension, yet trading with the others and welcoming them when they came. Women were no longer necessary to their society, nor were children. The Shadow Princes are a selfish race. Kind, but selfish. And so it has been for many centuries. Now and again new members are chosen for the council that the others are not made uncomfortable by their longevity and never-changing appearance. They take women they admire for their pleasure, but they always return them to their families with enough wealth to satisfy those families.”

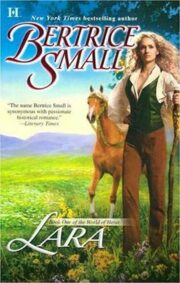

"Lara" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lara". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lara" друзьям в соцсетях.