“My fondness for Mr. deCourcy cannot be improved upon. I will always be grateful to him for his many kindnesses to my father.”

“He is truly the gentleman, to be sure, and quite distinguished looking for a man of his age. His nephew must resemble him, for it is said that Sir Reginald is quite frail and sickly. Have you met Mrs. Vernon’s brother?”

“Mr. Reginald deCourcy? Why, no. Do you know him?”

“We very nearly met him at Bath,” said Eliza. “He was at an assembly with our mutual acquaintance Mr. Charles Smith—a very high-spirited, forward sort of young man. I had hoped that he would introduce us, but Mr. Reginald deCourcy did not seem inclined toward talking much to anybody, and he did not stay above an hour, though Mr. Smith remained until the very last.”

“And what is Mr. deCourcy like?”

“He is certainly a handsome fellow, tall and a bit imposing in his bearing and countenance, but I suppose he has every reason to think well of himself, for there are few young men in England who will come into a better fortune. Try as we might, we did not see Mr. deCourcy again before we left Bath. Mr. Smith told us that his friend spent nearly all of his time at the library and declared that Mr. deCourcy was a very dull fellow, though I am certain that he exaggerates, for Charles Smith is the sort who always takes it upon himself to amend the truth.”

“Then perhaps in amending Mr. deCourcy’s character, he improves it, and in truth Mr. deCourcy is much duller than his friend reports.”

Eliza was about to make her reply when Frederica flew into the room with her hair disheveled and her apron strings flying loose. “Mama! Come at once! Father has been injured!”

Miss Wilson threw aside her needlework and rang the bell while Lady Vernon and Frederica dashed out of the house and tumbled down the sloping meadow to the wood. The two women had just reached the trees when they were met by a party of men who were carrying the senseless Sir Frederick. His forehead and one forearm were wounded and bleeding.

“Good God, what has happened to him!” Lady Vernon cried in great distress.

“I found him on the ground with his boot caught in a large tree root,” Charles Vernon stammered. “It must have tripped him up, and he struck his head when he fell.”

Lady Vernon took command at once and ordered one of the men to send for the surgeon while Sir Frederick was carried to his chamber. She then called for water and bandages, and with the assistance of her daughter and her maid, dressed her husband’s wounds while the others paced and asked each other if there was something more to be done.

The surgeon arrived, examined the patient, and praised Lady Vernon for her skill, declaring, “You must summon me at once if he regains consciousness, but until that time, you can only make him as comfortable as possible.” He then departed with a promise to return that evening.

Lady Vernon remained at her husband’s side, leaving Miss Wilson and Deane to perform her offices. Mrs. Manwaring suggested that a house full of company would only add to Lady Vernon’s burden and advised that they make preparations to depart. Manwaring argued against his wife’s proposal—they must remain, he was certain that Sir Frederick would wish them to remain—but the rest of the party was of the mind that they must defer to Sir Frederick’s brother, and Charles Vernon seemed very eager to have them go.

His presence proved to be more of a trial than a relief to Lady Vernon. His excessive agitation did nothing to promote an atmosphere of confidence and calm, and his attempts to take Frederica’s place at her father’s bedside were so persistent that they were an irritation rather than a comfort. Lady Vernon rebuffed him with as much civility as she could, but she could spare little attention for anyone but her husband.

Frederica would not yield her place to her uncle, but when Sir Frederick appeared to be sleeping comfortably, she slipped into his dressing room and, taking up a sheet of paper and pen, she wrote to Sir James.

Miss Vernon to Sir James Martin

Churchill Manor, Sussex

My dear cousin,

I would not trouble you when the business that has kept you from coming to us must be pressing, but a terrible situation has risen that compels me to beg for your immediate assistance. My father has been gravely injured and I know that my mother would be grateful for your counsel. She cannot leave my father’s bedside, or she would write to you herself.

Do come to us, but only if it can be managed to your convenience and without distressing my dear Aunt Martin.

Your affectionate cousin,

Frederica Vernon

Sir James was at Churchill Manor within twenty-four hours of the receipt of the letter, with a prominent Derbyshire physician in tow.

Charles Vernon was visibly alarmed when Sir James arrived, and his greeting was barely civil. “My niece was very wrong to distress you and Lady Martin.”

“She meant no offense, I am sure,” Sir James declared. “I am certain that Frederica’s only desire was to prevent Mother from hearing this unhappy news from another.”

“There is nothing at all to be done that the servants and my sister’s kind neighbors cannot do.”

“If that is the case, then you must not prolong your absence from Parklands,” declared Sir James coldly. “It may be days, or even weeks, before there is a change for the better or worse. You cannot be spared from your family for so long.”

Vernon struggled to conceal his chagrin. To endure days or weeks until his brother’s fate was known was a great hardship. If Sir Frederick was to succumb, would it not be better that it happened immediately, rather than eventually, and spare everyone the pain of agonized suspense?

Two days after Vernon’s departure, Lady Vernon and her daughter were sitting at Sir Frederick’s bedside when he opened his eyes and declared in a very weak voice, “Ah, what a fright you gave me. I thought at first that I had gone to the angels, but here it is my dear wife and little Freddie beside me.”

Lady Vernon wept with relief when she heard his words, and Frederica was so overcome that she began to sob and ran from the room. Sir James found her sitting in the garden, giving vent to her emotions, and he began to babble something about the grounds, mistaking a fir for a spruce and debating whether moss grew in the sun or the shade until Frederica was obliged to calm herself far enough to set him to rights.

Sir Frederick improved and soon was able to leave his chamber and sit with the family for part of each day. Sir James remained at Churchill, and his brilliant cheerfulness, when added to the gentle solicitation of Lady Vernon and her daughter, and the diversion of Alicia Johnson’s chatty missives, had a beneficial effect upon Sir Frederick’s health and spirits.

Mrs. Johnson to Lady Vernon

Edward Street, London

My dear Susan,

It grieves me immensely to think that Sir Frederick’s situation must keep you from coming to London at all. I cannot take pleasure in anything nor delight in going anywhere if there is not the possibility that we should meet. I dined with the Carrs two nights ago—they were very happy to take your house for the season, and I daresay they pay a generous rent, as they are come back from Antigua with a great deal of money! They had thirty at the table, but the conversation was exceedingly dull. She wore a gown of sarcenet beaded all over and pearls wrapped about her head—her gown was green, which did not suit her complexion at all, as she has gone very brown. Your husband’s brother was among the company and he was very attentive to Mr. Carr in the way that a banker will be toward anyone who has come into plenty of money. The evening was a very late one, with most of the gentlemen still at cards when I was obliged to leave. Bye the bye, Mr. Vernon was quite cool toward me, but I put that down to the fact that he was unsuccessful in getting Mr. Johnson to put money into some sort of scheme. Surely he cannot blame me if Mr. Johnson would not open his purse—it is all that I can do to get a few new gowns out of him every year.

I was obliged to drink tea with Colonel and Mrs. Beresford on account of their leaving London for Newcastle, and to go to the Millbankes’ on account of their son’s getting engaged to Miss Reed, and we had Mr. Lewis deCourcy to dine, as he was in town to direct some matters of business for the Parkers. They have got more money than is good for them, and I expect that they will soon look to purchasing something in the country. Mr. deCourcy has taken Sir James Martin’s house for part of the winter; he declares that Sir James does not mean to come to town at all for the season.

It is a great pity that Miss Vernon will miss her season in town, but if she would like some relief from the country, you may send her to me, and I will stand up with her. There are a fine crop of naval officers come through London, and they make for good husbands as they are like to spend much of their time at sea. How I wish that Mr. Johnson had gone into the Navy, though I cannot think that I would see any less of him than I do with him upon dry land.

There is a little something in the way of a dance at the Younges’ tomorrow night, but as they have taken a very cramped set of apartments on Argyll Street, I cannot think that I will take any pleasure in it.

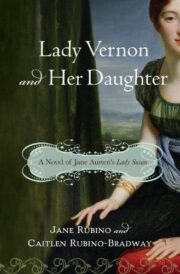

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.