“I cannot be at peace while you are in town—I will imagine you in all sorts of mischief!”

“Then at least you will never want for something to think about.”

“I would rather you stayed with us in Kent—then I would not have to think about anything at all!”

“I would not for anything deprive you of the pleasures of imagination. As for mischief, I can only promise to get in as little as any gentleman can when in town, and to assure you that there will be those who put their mothers’ imaginations to the task, and with far greater cause than I.”

This was no consolation for Lady deCourcy, however, and she passed the rest of the evening in grievances and whist.

chapter fifty-five

Mrs. Johnson to Lady Vernon

Edward Street, London

My dear creature,

How unlucky that you should have been from home when I last called at Portland Place—it is so provoking, for I have had such a tale to tell! The rumors of Miss Manwaring and Mr. Lewis deCourcy marrying are quite true, but it was not until just now that I have learned that they are to be married to each other! This I have on the indisputable authority of Eliza Manwaring, who has this moment left us.

I had gone to Bedford Square, to call upon Lady Hamilton and her daughters. Miss Hamilton and Miss Claudia were with their mantua maker, having their gowns for Sir James’s ball finished, but Lady Hamilton was sitting with her youngest daughter and her husband. Mr. Smith has learned that forgiveness for his conduct is very easily come by—he has only to flatter Lady Hamilton and agree with her every opinion and pronouncement to be declared “a very agreeable sort of young man.”

I returned to find Eliza sitting with Mr. Johnson, and I had no sooner stepped into the room when Eliza demanded my congratulations upon Maria’s engagement and added, “They have both been so cautious—I do not call it a real courtship at all! Mr. Johnson has already heard the news, as he and Mr. deCourcy are such good friends, but you must confess yourself surprised, Alicia.”

“Mr. deCourcy!” I cried. I quite naturally supposed that she spoke of Mr. Reginald deCourcy—for he and Mr. Johnson are the greatest friends in the world since their introduction—and yet I could not believe that he would desert you for Maria Manwaring.

I cannot describe my shock when I was undeceived, and I shall never forgive Mr. Johnson, for he must have known this for a fortnight at least! Maria Manwaring and Lewis deCourcy! He must be thirty or more years her senior! He is very rich, of course, and Manwaring will be very happy to have her off his hands—indeed, you will have to be very prudent, as this is likely to make Manwaring more indiscreet than ever in his attentions toward you. I fear he is capable of some great imprudence and may act in such a way as to excite deCourcy’s jealousy and to make you miserable. I advise you, therefore, not to put off your marriage until Miss Vernon’s is a settled thing. You must think more of yourself and less of your daughter.

Mr. Johnson has reconciled himself to Eliza so far as to invite her and Maria to stay with us at Edward Street for the present. Such a reversal in feeling, such goodwill where there was once censure! Men are such inconstant creatures!

I am not disinclined to have Maria here. She will want a great deal of looking after now that she is to be married, and Eliza has been so little in town that she will not know where the best shops and warehouses are. And while she and Manwaring will not see each other, I am on such terms with Manwaring that I must necessarily be the proxy—I am certain that I can get him to spend more than he will be inclined to for Maria’s wedding clothes.

It is my understanding that Mr. deCourcy and his nephew have gone to Parklands to bring Maria and Miss Vernon back to town, and perhaps when they are settled, we may all make a little party of going around to the warehouses together?

Yours, &c.,

Alicia Johnson

Lady Vernon had received a note from her daughter announcing the day and time when she might be expected back at Portland Place. She was very surprised, however, when Lady Martin ran into her dressing room at the appointed hour, crying out, “My dear, the whole party from Kent has just this minute drawn up to the house in a barouche, and Frederica rides in the box with Reginald deCourcy! And what do you think? His father is among them!”

“He will not come in.”

“I daresay not, but it is a great compliment to Miss Manwaring and Frederica that he should accompany them.”

The eager footstep of Frederica was heard upon the stair and a moment later, she was in her mother’s embrace and then gave an equally affectionate greeting to her aunt and Wilson. “But you must come down to the drawing room, for Sir Reginald deCourcy most particularly wishes to be introduced to you.”

Lady Vernon was all astonishment—that the gentleman who only months earlier had written of her in such critical terms should call upon her immediately upon his arrival in town was a great compliment—and sending her aunt and daughter down to their guests, she asked Wilson to arrange her gown and shawls in order to conceal her condition as well as possible, before she joined the party.

The formidable introduction was made, and Reginald, who had watched with some apprehension as his father was presented to Lady Vernon, was relieved to see that the gentleman’s conduct was courteous and civil and that the lady’s every word revealed her superiority of taste and manner. Her warmth toward his brother and Miss Manwaring, her unreserved happiness in their engagement, advanced Sir Reginald’s good opinion of her.

For her part, Lady Vernon was pleased that Frederica was the subject of so much of Sir Reginald’s discourse (and with very little prodding from Lady Martin upon her niece’s looks and accomplishments); in recalling the many pleasant hours they had spent at Parklands, the old gentleman gave every indication of his regard for Frederica, and Lady Vernon was convinced that when Reginald did ask for her hand (as his looks and words toward Frederica gave every indication that he would) his father would not object to the match.

Their visitors stayed with them above half an hour, and when they walked out to their carriage, the shades upon many upper windows fluttered, and it was whispered in several drawing rooms that the appearance of Sir Reginald deCourcy at Portland Place must mean that he had relented and given his consent to his son’s marrying Lady Vernon at last.

chapter fifty-six

Charles Vernon had not been pleased when he learned of Lewis deCourcy’s engagement to Maria Manwaring. Although it was not likely that the union would produce any future claimants upon Parklands, it was hard to think that the considerable fortune of his uncle would go to a penniless girl, for Lewis deCourcy was the sort of gentleman who would not think of marrying anybody without first settling how she was to be provided for upon his demise. His sympathies might still be played upon—he might be persuaded to settle something upon the children—but Charles must give over all hope of having any of Lewis deCourcy’s fortune come to him.

His disappointment was offset, to some degree, by the satisfying news that Sir Reginald had come to town. Charles rehearsed a proposal to relinquish his rooms in order to reside with his father-in-law, an offer that began with an earnest desire to be of use to Sir Reginald and concluded with a list of residences that were suitably quiet, convenient, and grand. He determined that the arrangement would entail no more than occasionally writing letters of business or performing some commission in the city, a small sacrifice for securing a handsome address in town.

Charles received word of his father-in-law’s arrival and immediately waited upon him at Reginald’s address in very sanguine spirits, which supported him until he was ushered into the gentleman’s presence. Then his confidence weakened, for Sir Reginald’s appearance and demeanor were no longer fragile and retiring; instead of losing ground since they had last parted, Sir Reginald now appeared to be in very good health—his complexion was ruddy, his eye sharp, and his voice clear and resolute.

Charles stammered out a greeting and could not help adding, “I am surprised to see you looking so well, sir.”

“I am well, which I must attribute to the advantage of good company—of Miss Vernon and Miss Manwaring I cannot speak too highly, and I am always happy to see Catherine and the children. But you appear more surprised to see me in health than pleased about it.”

Charles’s protests were cut short by Sir Reginald, who added, “You can, however, be no more displeased than I, as I hear accounts of your conduct that disappoint me exceedingly.”

“I cannot imagine. What can you allude to?”

“Churchill. Churchill—that word should be sufficient.”

Charles first went white and then colored deeply. “Churchill?” he stammered. “How can the single word ‘Churchill’ be interpreted to my discredit?”

Sir Reginald needed nothing more than the look of guilty apprehension upon his son-in-law’s countenance to confirm that his suspicions, which he hoped had imputed too much to Charles, had instead assigned too little. “Do you require particulars?”

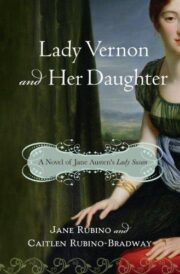

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.