chapter fifty-two

Mr. Vernon to Mrs. Vernon

Bond Street, London

My dear wife,

If I have not been a very regular correspondent, it is because I must suppose that anything of note has already been communicated by Reginald, whose range of acquaintance affords him society and engagements more extensive and varied than my own—even those invitations that come to a gentleman in my profession must often be declined as my modest rooms put it out of my power to reciprocate in the same style. I often think it a great pity that your parents had never thought it prudent to take a house in town, if not for their own pleasure, then for the pleasure and convenience of Reginald and ourselves. Even if I were to leave the banking house (as it is no longer necessary for me to have an occupation), my new situation must require that part of the year be spent in town. To do otherwise would be to deprive our children of the society from which the very best matches will proceed. How such an establishment is to be managed must wait upon a better understanding of how far the income of Churchill Manor will allow it—and yet it would be a great pity not to have an establishment sooner.

I am very glad to hear that my father-in-law is in improved health, and it occurs to me that if he is fit enough to travel, he may well wish to consult with one of the superior physicians in town. There are several very fine houses to let, and I am certain that I could find one that would suit Sir Reginald in every way. I know that my uncle goes to Parklands very soon to fetch your two young visitors back to London, and I think very little persuasion on your part will be wanted to have your father return with them. Lady deCourcy, I know, does not like London and will wish to continue with you and the children at Parklands—you may both be assured that if Sir Reginald does come to town, I will be very happy to attend him in any way he likes.

I think that our Uncle deCourcy would also like to have his brother in town for a reason that will come as a very great surprise to you—here is a bit of news! It is being said that he has come to an understanding with Lady Martin! I have this from Mrs. Johnson—I dined with the Carrs two nights ago and she was of the party—and it was declared to be a settled thing that our uncle is to marry. As this is news that cannot be withheld indefinitely from his family, I believe that Mr. deCourcy means to surprise you all with the news when he comes to Kent—you may have the advantage of him now, as I now know that we are both of the opinion that such surprises are very disagreeable things. Indeed, this news would be a most unpleasant surprise if it were to have an injurious effect upon our own fortunes—the deCourcy family can only benefit, however, as it is said that Lady Martin has something in her own right, which, if it does not come to a husband, would likely be settled upon Lady Vernon or her daughter. Indeed, the house in town that Lady Vernon now occupies was settled upon her by Lady Martin, thus putting it out of Sir Frederick’s power to direct that all of his property pass to his heir (which, I am certain, would have been his wish). Indeed, I think it is Lady Vernon who could do well with a comfortable set of rooms more easily than I, as she does not give any parties or dinners and leaves it entirely to her aunt to repay all of their calls.

I have, on occasion, stopped at Portland Place, but spoken only to Lady Martin, who said that Lady Vernon was unwell and could not receive visitors. I have heard that she is visited very regularly by a prominent physician, and, my dear wife, though I would not indulge your hopes prematurely, who is to say what may come of that? The influenza is not nearly so widespread as it is rumored—nobody of consequence has died of it—but if she were to be the first, we can hope for no better outcome of her inevitable marriage to Reginald, as it might leave him in possession of the Portland Place residence yet without the encumbrance of such a wife. The loss would, of course, take its toll upon such a sensitive nature as Reginald’s and likely keep him from ever marrying imprudently again. I must write no more, for to do so would unreasonably excite our hopes by fixing them upon an event that may not come to pass.

Of Reginald, I can write very little. In town our obligations and associates take us into very different circles. I see him occasionally at White’s.

I have taken your rings to Rundell’s, and the stones have all been reset as you have directed.

Your devoted husband,

Charles Vernon

Catherine Vernon read this letter more certain than ever of her husband’s solicitous and accommodating nature. To think of Sir Reginald’s health, to offer to attend to him in town, and even to offer her the hope that the wretchedness of Reginald’s union with Lady Vernon might be short-lived, exceeded all of her former notions of her husband’s benevolence.

She was very surprised, however, to hear that her Uncle deCourcy might think of marrying at so comfortable and settled a stage of his life, a feeling that was shared by Lady deCourcy, to whom she read her letter.

“I am quite shocked,” she declared. “There were one or two very eligible young ladies whom he might have married, though I do not think that Elinor Metcalfe was ever among them. Well, I cannot blame your uncle. If an opportunity to increase his wealth should come his way, it is his duty to take it, for the sake of you and Reginald, who inherit his money and property when he goes. Her motives are more incomprehensible to me, for being so comfortable a widow, what reason can she have to marry again? Could she be so fond of your uncle that she would sacrifice every worldly advantage to feeling? Your father will be quite shocked—I daresay it will set him back a great deal. He does not bear anything like a surprise as well as you and I do.”

Lady deCourcy was very soon called upon to suffer a surprise, however, when, from her dressing-room window, she saw her son alight from Lewis deCourcy’s carriage. She ran straightaway to Catherine’s apartments, crying out, “Reginald is come! What can have compelled him to come away from town with his uncle? Can it be that he and Lady Vernon have parted? It is too much to hope for! I must go down directly—you must hurry and dress. Miss Vernon is somewhere about the grounds with your father! Call Miss Manwaring to help with the children.”

She then ran downstairs and out the door to meet the two gentlemen. “My dear boy! You have come back again! Oh, how will your father bear the pleasure of seeing you home again so soon! I fear it will send him back to his bed! But how long do you stay—you must not hurry back to town.”

“I am afraid that we stay only a very short time, Mother. We are charged to bring Miss Vernon and Miss Manwaring back to town.” He then inquired after Sir Reginald and was told that he was somewhere on the grounds with Miss Vernon, whereupon Reginald walked out to find them while Lady deCourcy hurried back upstairs to Catherine.

“How does Reginald appear?” inquired Catherine. “How are his spirits? Is he very low? Can Lady Vernon’s spell over him be broken?”

“It is almost too much to hope for—and yet there was no need for him to accompany your uncle unless he wished to get away from London. Your uncle’s prudent decision to marry Lady Martin must have awakened Reginald to the necessity of choosing dispassionately and with regard to his family—perhaps I may write to my dear sister Hamilton that all is not lost.”

Reginald, meanwhile, had been directed by the groundskeepers toward the summerhouse. There he spied his father and Miss Vernon examining some of the water plants upon one of the ornamental ponds. He was delighted to see his father in such improved health, for his color was robust and when he spoke his voice was clear and strong.

The elder gentleman was attending to Miss Vernon as she pronounced one of the plants to be a water hawthorn, “as there are very few pond plants that will show any bloom this early—the scent of vanilla, too, pronounces it most certainly to be water hawthorn.”

Sir Reginald began to inquire whether the plant was known to have any curative properties when he spied his son. He greeted him warmly and said, “I trust that your journey was easy and that I will find my brother well.”

“In health and in spirit, I have never seen him better,” replied Reginald. “And,” he added, addressing Miss Vernon with a knowing smile, “I hope the same may be said for your friend, Miss Manwaring?”

“I think that the very same may be said for her, sir.”

Mr. deCourcy then told Miss Vernon that he had seen her mother and aunt only the day before and was gratified to hear his father inquire, “I hope that you left them both in very good health—and I hope that you, Miss Vernon, will convey my thanks to them for giving up your company these four weeks so that you might study the curiosities of Kent.”

They found the rest of the party in the sitting room, and for half an hour Lady deCourcy kept them from anything like conversation by declaring again and again that the month had gone by very fast and that if the young ladies were of a mind to stay another fortnight, they would not at all be in the way. “Lady Vernon can certainly spare her daughter, and Miss Manwaring has only her brother and Mrs. Manwaring in town—and sisters and brothers are more often apart unless some unfortunate circumstance of economy should compel them to live together.”

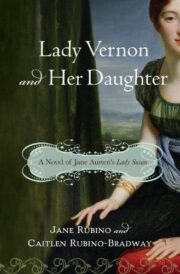

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.