Here he paused and looked at her expression before deciding whether he should continue.

Lady Vernon was dumbfounded. She had always liked her cousin—nay, she loved him—with all of the warmth and affection of two people who have known each other since childhood. No match could suit either of them better, for she was inured to all of his faults and he was so in love as to be persuaded that she had almost none at all.

“I have forgot,” Sir James continued, “the fervent assurances that I love you beyond expression. You will forgive me if I have overlooked what ought to be said at the outset. Though I have been said to be on the verge of marriage with every eligible young lady in England, I am quite a novice at the business of proposing—nor do I have any ambition to become a proficient.”

Lady Vernon needed no such assurance. That Sir James loved her, she was certain. But would he have offered his hand if he knew that it would obligate him to Sir Frederick’s unborn child? “I am not yet out of mourning.”

“I am not proposing that we elope, Susan. That is for the likes of Charles Smith and Lucy Hamilton. I only ask for the permission to hope.”

“I would be very wrong to encourage such a hope. My own prospects are so uncertain that yours may be injured by affixing your fortunes to mine. Did you not pronounce marriage to be a business transaction that one should not enter without a promise of a return? I encourage you, as a cousin who has loved you all her life, to aspire to a happier and richer union than I can offer.”

“I do not look to be enriched by marriage, only to be happy. I entirely comprehend your hesitation, but you need have no anxiety on Freddie’s account,” he hastened to assure her. “Tomorrow I journey to London with deCourcy and I will impress upon him any of Freddie’s perfections that have escaped his notice—it will take far less than thirty miles to accomplish. They will be married in six months.”

“A great deal may change in six months,” Lady Vernon replied. “Your nature and inclinations are such that in half a year’s time you may regret your offer to me.”

Sir James was affronted and almost angry. “When have I ever wavered in my devotion to you? When have I ever given you cause to think that I would tender my proposals to anyone without sincerity? I do not deserve such censure.”

Lady Vernon had never seen him so carried away by emotion. “I beg your pardon, cousin. I do not censure you—indeed, I have always relied upon your devotion.”

“And you may continue to rely upon it. If six months’ time should bring about any change in me, it will be that of a more determined attachment.”

“If that is true, you will not object to postponing your addresses. In six months’ time, if your attachment is not what you declare it to be today—if some circumstance should arise that would make you unwilling to renew your proposals—you will suffer neither reproach nor blame from me.”

“I assure you that in six months the only regret I will feel is the loss of so much time to suspense and anxiety when I might have been happy and secure. But it is no sacrifice—indeed, as Frederick has been gone barely six months, it is no more than is due to his memory.”

Lady Vernon was resigned to her cousin’s determination to be happy and decided that it was better to let the passage of time, and the event that it would bring about, test the depth of his fidelity. She extended her hand and he kissed it, both perfectly satisfied that the matter was resolved.

Volume III

London and Kent

chapter forty-two

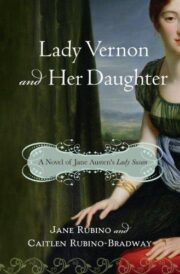

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.