“If you can give me your assurance of having no design beyond enjoying the conversation of a beautiful and clever woman, I may be restored to some measure of ease while you are away from us.

Lady Vernon met this insult with equanimity. “This is a very strange opinion of me, indeed, and I must confess that I cannot hope to do it justice. To be at once poor and extravagant, dissipated and clever, is more than I can manage, I assure you.”

“You make light of the situation?”

“Can I do otherwise? How would anger and hostility serve me, particularly when they are directed at a man of Sir Reginald deCourcy’s reputation? I would only appear the worse for expressing resentment against a gentleman who is so universally respected. But how can your father, a man to whom I have never even been introduced, have come to these conclusions, particularly if Charles has always represented me in the best light?”

“Something must come from my father’s sister, Lady Hamilton. It was she who informed him that you strongly objected to Mr. Vernon’s marriage to my sister, and that this opposition was widely known.”

“It cannot have been widely known if Sir Frederick and I were ignorant of it,” Lady Vernon replied. “We were not even aware that Charles was acquainted with your sister until we were informed of their engagement, and we learned of it then only when he made us an offer for Vernon Castle. Our only objection to anything was to that, for his offer was very low and our circumstances obliged us to get as fair a price as we could. We might have yielded, even at the expense to ourselves, had we not been confident that a marriage to Miss deCourcy would give Charles the ability to purchase wherever he liked and that he would not even have to depend upon coming in to Churchill Manor in order to be well settled. As for the rest of your father’s letter, I cannot account for it. I can only conclude that whenever an unmarried woman and a single gentleman are under the same roof, someone or other will have them at the altar. Still, your family cannot believe that, as you are engaged to Miss Hamilton.”

A troubled look passed over Reginald’s countenance. “There is no engagement. Since we were children, my parents and the Hamiltons intended us for each other, but I have made no proposal to my cousin.”

“When you do address her, your father will be more at ease.”

Reginald made no reply.

“But,” Lady Vernon added with great perception, “if you are not inclined to marry her, you only prolong your family’s groundless hopes and the expectations of Miss Hamilton when you do not make your wishes plain.”

“It is not an easy thing to disappoint one’s family.”

Lady Vernon smiled. “You must think better of your family. My family had settled on someone other than Sir Frederick for me, yet when inclination drew me to another, no estrangement from my parents resulted from it.”

“Because they yielded to your preference,” he remarked. “And perhaps my own would do the same if there was any young lady I preferred to my cousin, but alas, I cannot even argue that I am partial to another.”

“Still, you must not delay a response to your father. If you cannot bring yourself to disappoint him in his hopes just yet, you must at least tell him plainly that there is no foundation for his present fears. You must not allow gossip to injure his peace of mind.”

He admitted to the soundness of her advice, which was given without any of the attendant arguments and sermonizing that Catherine would have thought necessary. They returned to the house and parted in the hallway, he to write to his father, and she to reflect upon how different her opinion was of Reginald deCourcy than it had been only a fortnight earlier. As they advanced toward something like confidence, she discovered a thoughtfulness of manner and expression that she liked very much, and though he was not without faults, they were principally the faults of youth rather than understanding. If he was too quick to form an opinion, he was always ready to admit his error, and if he was often too inquisitive and demanding of particulars, he was never uncivil.

She could no longer disallow Alicia Johnson’s expectations—indeed, Lady Vernon now was thinking of Reginald and marriage together, but the partner she had chosen for him was not herself (however flattered by her friend’s conviction that it was in her power) but Frederica. Though little exposed to society, her daughter was Reginald’s equal in education and refinement, and though her fortune was insignificant, she was the daughter of Sir Frederick Vernon and the niece of Lady Martin. If Reginald was not bound by honor or promise to his cousin, and if his father asked only that he choose a woman of unexceptionable family and character, was not Frederica a worthy choice?

“He appears a willful young man,” declared Wilson, “but there is something to be said for a spirit that has borne up against Mrs. Vernon and Lady deCourcy. The right young lady might take away that last bit of conceit in his manner, and then I will like him almost as well as I do Sir James. But,” she added, “if he believes that Miss Frederica is intended for Sir James, he will not put himself forward.”

“I think he would put himself forward because he believes she is intended for another, and if he is persuaded that she is opposed to the match, so much the better. He has the deCourcy stubbornness after all, and will go after what he thinks he cannot get.”

chapter twenty-seven

Mrs. Johnson to Lady Vernon

Edward Street, London

My dear Susan,

I wish you the very best greetings of the season and suspect that this may be among the last letters in which I will address you in the name of “Vernon,” as, despite your protestations, you are likely to take up another name in the coming year. Until that time I caution you to be on your guard against Manwaring. He is so determined to avoid Eliza in town that he talks of accompanying Maria when she goes to Billingshurst in January—he will take any excuse that brings him down to Sussex, and if he comes as far as Billingshurst, he will be teasing you to get him admitted to Churchill. A little jealousy is a good thing, but Manwaring’s may lead him to press his suit in a manner that will strain your understanding with Mr. deCourcy.

Miss Vernon continues as obstinate as ever, and her opposition to marrying Sir James—which is talked of everywhere—ought to be very provoking to Maria Manwaring, who has tried to get him for so many years. And yet they are fast friends! What a perverse world it is!

Until that union can be accomplished, we are all diverted by a courtship of another sort. The youngest Miss Hamilton gave up her Christmas visit to Parklands Manor on purpose to stay in town and carry on a flirtation with Charles Smith! His wooing is copied out of the worst sort of romantic novel, but as she never can read two pages before she is overcome with boredom, she finds his flattery quite original and is silly enough to think that he would take her if she did not come with thirty thousand!

If nobody intervenes to prevent it, I suspect she will do something foolish. What a delicious scandal it would be to have the eldest Miss Hamilton cheated out of a match with deCourcy and the youngest throw herself away on Mr. Smith.

Adieu!

Your affectionate friend,

Alicia Johnson

Lady Vernon could only shake her head at her friend’s stubborn conviction that a marriage with Reginald deCourcy was her object.

“Is your letter from Miss Vernon?” inquired Reginald politely (as they were at the breakfast table).

“No, it is from my friend Mrs. Johnson.”

“I do not think that you have had one letter from Miss Vernon in all the time you have been with us,” observed Catherine. “Our mother writes to me that Lady Hamilton has had a half dozen letters from Lucy since she has been at school.”

“Perhaps,” Reginald said with a smile, “Miss Vernon does not possess our cousin’s freedom of expression and quantity of paper.”

“I am sure that anything Frederica would like to say will keep until I go to London,” said Lady Vernon.

“Oh, but it is too early to talk of your departure!” cried Charles, who did not wish her gone until she had got Reginald to make her an offer. “We will not think of your leaving us, do you not agree, my dear?”

Catherine did not agree. She looked eagerly toward the date when Lady Vernon and Reginald would be divided before any real harm was done. She said nothing until Lady Vernon left the room and then immediately exclaimed, “How very deficient our niece must be in her education! Not one letter all this month! Such a negligent correspondent! Such indifference to duty and decorum does not speak well for the manner in which she was brought up.”

“You judge the custom of all daughters by your own, Catherine,” said Reginald. “Perhaps it is not that Miss Vernon writes too seldom but that you write too often.”

Catherine favored him with a reproving glance. “Indeed, one cannot write too often,” she replied. “I begin to understand Lady Vernon’s eagerness to hurry along her daughter’s engagement. It is likely that Miss Vernon is so wanting in character that she is past reform, and Lady Vernon may want her married before Sir James can find it out.”

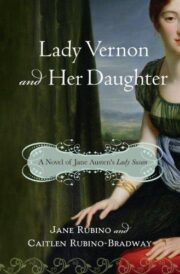

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.