Sir James, however, was too impetuous—upon receiving her letter, he immediately dashed off a reply full of astonishment and anger; Lady Vernon found herself smiling at his excessive expressions, certain that the next day’s post would bring a retraction that was equally immoderate in its remorse and affection. Lady Martin’s letter was more resigned.

I am excessively disappointed that you did not come to us. I shall have to put up with James until the new year, with nobody to relieve me of his company. But do not be alarmed for me—if he becomes too troublesome, I have only to remark upon the shabbiness of his attire to get him off to his tailor in London. That is always sure to get me a fortnight of peace and quiet.

The next letter had her address penned with all of the loops and flourishes of a female hand, but when Lady Vernon opened the sheet, she saw that it was from Manwaring. She read, not without amusement, his dismal accounts of the tedium of Langford and his eagerness to quit it for London.

And when I get to town, you may write to me under the cover of our mutual friend, Alicia Johnson. You need have no fear of our correspondence being intercepted, as Alicia tells me that Mr. Johnson has accepted an invitation from Mr. Lewis deCourcy to pass a few weeks at Bath. Mr. Johnson continues to hate me for taking away his ward when he was so opposed to the match, and I confess that I begin to be on his side. Alicia, however, likes to be on the side of whoever gives her the greater share of participation in a romance. We must not disappoint her.

The last letter was from Mrs. Johnson.

Mrs. Johnson to Lady Vernon

Edward Street, London

My dear friend,

We have been very dull here, but it promises to be more exciting, as Manwaring (who has contrived, in spite of Mr. Johnson, to get a letter to me) will come to town before Christmas. He is in a deplorable state and laments over your premature departure from Langford as fervently as Eliza delights in it. I advise you to be as firm with him as you can, lest he commit the grave impudence of attempting to come to you at Churchill. It is said that he will take rooms on Bond Street, and leave Maria and Eliza to shift for themselves. Everything points to a strong desire on both sides to part, and it is only the mutual ambition to get Maria married that keeps them from acting upon it.

Mr. Johnson leaves London next Tuesday. He is going for his health to Bath. He will stay with Mr. Lewis deCourcy, and during his absence I will be able to choose my own society and receive Manwaring without Mr. Johnson reminding me that I had once made some sort of promise never to invite him to our home. Nothing but my being in the utmost distress for a new gown and some ready money could have extorted such a pledge from me, but I consider my promise to Mr. Johnson as comprehending only that I do not invite Manwaring to sleep in the house or to eat anything beyond a cold luncheon or tea.

Poor Manwaring! In his letter, he gives me such histories of his wife’s jealousy! Silly woman, to expect constancy from so charming a man! But she was always silly; intolerably so, in marrying him at all. She was the heiress to a large fortune and nothing else—neither looks, nor good humor, nor sense—she might have had a title and instead settled for a man without a shilling to his name!

I do not in general share the feelings of Mr. Johnson, but when I heard of what she threw away, I quite understand his resolve never to forgive her.

I have had Miss Vernon twice to tea and once to dine—a difficult enterprise, as the conditions under which Miss Summers’s charges are permitted to leave the premises are very strict. Your daughter bade me to send you her love and says that she has directed a letter to you by way of the parsonage.

Your affectionate friend,

Alicia Johnson

Lady Vernon had been anxious that she had received no word from Frederica, and rising from the table, she announced her intention to walk to the parsonage and call upon Mrs. Chapman.

Charles Vernon seemed very much alarmed. Though he was not comfortable in his sister-in-law’s presence, he did not like to think of her running all over the county and engaging the sympathy of the neighbors. “But see how dark the sky is!” he protested. “It will surely rain.”

“It is only a passing cloud or two.”

“Then perhaps Catherine will accompany you. Do you not wish to call upon Mrs. Chapman, Catherine?”

“Indeed, no,” replied his wife. “I called upon her only last week—my mother does not call upon the parsonage at Parklands Manor above twice a month.”

“I would not take Mrs. Vernon away from her more pressing obligations,” said Lady Vernon mildly. “I will take Wilson with me.”

“If you will wait, I will call for the gig and drive you myself,” Charles offered.

“That will not accommodate three of us,” Lady Vernon reminded him. “But you are most welcome to walk with us, brother, and we may stop at the churchyard on the way. I ought to have visited Frederick’s gravesite upon my arrival. I must not neglect it any longer.”

Charles immediately recollected some urgent letters of business that must be written that morning, and stammering an apology for withdrawing his offer, he hurried from the room.

Lady Vernon and Wilson made their way along the neglected road, where it was passable, and crossed lawns and fields, where it was not, until the white fence surrounding the graveyard was in view, and when Lady Vernon saw the stone marker, with nothing upon it but a few humble blossoms, tokens that must have been left by some kindly tenant or villager, she began to weep. Wilson waited patiently while her mistress had her cry and then helped Lady Vernon to wipe her eyes and adjust her veil before they continued on to the parsonage.

Mrs. Chapman was delighted to see them both but declared that she was very surprised to hear that they had walked from Churchill Manor. “For Mrs. Barrett and I called at Churchill Manor not two days ago, and Mr. Vernon informed us that you were too fatigued from your parting from Miss Vernon and your travels for any visiting at all.”

Lady Vernon did her best to conceal her astonishment. “I am sure that you misunderstood—I will always be happy to see my old friends while I am at Churchill. I quite depend upon it.”

Mrs. Chapman then produced a letter from Miss Vernon. “I got a very pretty note from Frederica—how handsomely she expresses herself—and she enclosed this sheet for you. How I do miss her! Only last year she got my little hothouse going so well that Mr. Chapman and I shall have strawberries into January. What a pity Mr. Vernon has lost most of your groundsmen—I am afraid that Miss Vernon’s gardens and greenhouses have quite gone down since your departure.”

Lady Vernon took her leave soon after this exchange, but not before she had got Mrs. Chapman’s promise to wait upon her at Churchill Manor.

As they walked back, Lady Vernon opened her letter and read it aloud to Wilson.

Miss Vernon to Lady Vernon

Wigmore Street, London

My dear Madam,

You will forgive this expedient for sending my letter, but I do not know who takes in the post at my uncle’s house—I do not think that he would scruple to open my letters.

I am getting along well enough here. Each morning we are tutored in deportment and elocution, French, arithmetic, and music, and in the afternoon it is needlework, drawing, and handwriting, after which we are left alone until tea. The other girls employ this time in gossip or trimming bonnets or filigree work, or practicing the new steps taught by the dancing master, who visits once a week. The library is a very poor one, and I do not think I have seen any of the girls take up a book unless it is one of their own novels, which they read aloud and exchange among one another.

We may receive visitors in the open salon but may not go out on our own, and if we are invited anywhere, a carriage must be sent for us. I have been to the theater once with several of the other young ladies, and have gone to Edward Street twice to drink tea and once to dine tête-à-tête with Mrs. Johnson. She laid down a good many hints about Sir James and myself and asked questions that I did not know how to answer. I turned the conversation aside as well as I could, and fortunately there is enough going on at Miss Summers’s to supply the diversion.

Lucy Hamilton is immensely popular and receives many invitations, but the only ones she accepts are those where she expects to meet with Mr. Charles Smith, who, it is said, has come to London on purpose to pursue her. It seems that Mr. Smith has been very much in the company of Mr. Reginald deCourcy, which cannot speak well for that gentleman—at Langford, Mr. Smith was so artificial and vain that his friends must be equally so. I do not envy Miss Lavinia Hamilton her prospective husband.

Lucy teases me a great deal about my “beau,” and will call me “Lady Martin,” and the other girls follow suit. They are all convinced that I have been sent here because I have refused Sir James and think that I am a great fool to set myself against someone who is so handsome and rich.

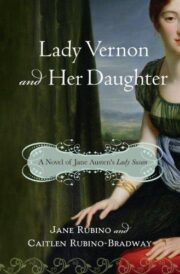

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.