“A very sound answer,” Sir James replied. “What goodness and compassion! Can you have acquired it without any encouragement from your parents? Surely something must be attributed to maternal influence.”

Lady Vernon found herself smiling and realized that she had believed that she ought to be angry with her cousin after all sensation of anger had gone. She had never been able to remain cross with him for very long. His liveliness, good humor, and wit were the sort that might test one’s patience but never provoke a permanent ill will.

“Come, Susan, sit down on this bench here in the sun—you are far too pale. Freddie, walk to the greenhouse and let me talk to your mother alone. Then I will come join you and cut one of the roses for you on purpose to vex the Misses Hamilton.”

“It is wrong to encourage discord, cousin.”

“It is worse to encourage hope.”

Frederica gave him a reproving smile and left them alone.

“It is good to see her smile,” Sir James remarked.

“She has had little enough to smile about.”

“Do you still mean to send her off to school?”

“Frederica can have no better opportunity to acquaint herself with the advantages and manners of London,” Lady Vernon replied. “She has seen too little of the world.”

“Perhaps she is all the better for it.” After a moment’s reflection, Sir James added, “Susan, I do ask you to forgive me and offer you Vernon Castle if you like. The Edwardses are very genteel, unimaginative folk who did not move a chair nor trim a hedge—it will all be as you remember it. They depart after the Christmas season. It can be yours on the first of January.”

“I do not wish to be as far from Freddie as Staffordshire. Not every mother can be like my Aunt, who looks to the first of the year when she can send you off to London and enjoy Derbyshire in peace and quiet.”

“Too much peace and quiet will dull the mind—think what Mother would be if she had no troublesome son to whet her better nature and to sharpen her wits upon! She might have sunk to an Eliza Manwaring or a Lady Hamilton. Every mother should have such a son, do you not agree?”

“We all have our share of maternal pride, cousin. I think as well of my daughter as any mother does of her son—I wish for nothing more, except perhaps some assurance that it will be in her power to attract a husband of consequence.”

“How can you say so when everyone whispers that she is being sent to London in order to be finished for me?”

“You may laugh as much as you like, but I cannot afford to be diverted where Freddie’s future is concerned.”

“I will not laugh, I cannot laugh, if you cannot afford to share my mirth. Come, Susan—we are not good at keeping secrets from one another—what allowance will you have for your diversion?”

“Per annum?” she returned with a renewal of spirit. “I think that it will be something more than you paid for the new mantelpiece at Cavendish Square and considerably less than the annual bill from your tailor. Now, do not look grim, cousin, and do not think of making us the object of your charity once more. We will not want for a roof over our heads.”

“I do not like that it is Manwaring’s roof,” replied he. “I like it even less than I did when I left you at Churchill. Manwaring’s attentions have made you the object of some very unpleasant talk—the gentlemen, of course, can say nothing offensive in my presence, but the ladies do not have to be so circumspect. They may cast as many winks and allusions as they like and have no fear of a calling-out.”

“I am not wounded, cousin. Lady Hamilton’s wit makes for a dull weapon.”

“She is not to be taken lightly, Susan. Her connection with the deCourcy family means that everything she sees here will find its way to Mrs. Charles Vernon.”

“I am convinced that Mrs. Vernon cannot dislike me more than she does already. I am grateful to Lady Hamilton for giving her niece some foundation for her aversion. I would not want to be hated for nothing.”

“My dear cousin, I beg you to bring your visit to an end when you take Freddie to London. That is my only business here. If you do not wish to come to Derbyshire and do not like to open your house in town, you may have mine on Cavendish Square, and I will take a set of rooms somewhere. Everyone will anticipate that we are planning my engagement to Freddie and she will become such an object of interest that some rich, headstrong young man will hurry to address her just for the fun of cutting me out. Every party will come out the winner.”

“Save for you. You will be as idle and giddy and single as ever. Go to Freddie, James, and let her tell you how many uses she has found for the Manwarings’ lovage leaf and archangelica. Let me sit and enjoy a few moments of tranquillity—that is such a rarity at Langford.”

He laughed and went off to walk with Frederica, while Lady Vernon sat down on a bench to reflect upon her cousin’s advice. She had erred in coming to Langford, not because she had encouraged Manwaring’s flirtation, but because she had removed from Charles Vernon’s consciousness the discomfort that her presence must have wrought. She could not dispute his right to deprive her and Frederica of all that Sir Frederick meant for them to have, but she might not have allowed him to be so easy.

Although Frederica, in her account of Sir Frederick’s injury, had suggested that her uncle had not acted as promptly as he might have, Lady Vernon was willing to concede that his hesitation may have come from shock and dismay rather than a malicious desire to see his brother perish. Yet, however pardonable his motives may have been then, his subsequent visits to Churchill Manor and his continual attendance upon his brother must now be seen as hopelessly, heartlessly mercenary. In persuading Sir Frederick against assigning any part of his fortune to Lady Vernon and her daughter, he had eased his brother into complacency and indefinite delay in the hope that it would be to his advantage, and with that as his object, could he do other than rejoice at its fulfillment?

The sound of horsemen aroused Lady Vernon from her reverie and she looked up to see Manwaring alight from his horse and hand the reins over to his groom.

“How fortunate that I should find you without a party of a half-dozen to act the chaperone! Which walk do you take? Do you prefer the park or a country lane?”

“I came out only to meet the post,” she replied, turning back toward the house. “I am expecting a letter from Miss Summers’s Academy—the arrangements for Frederica’s placement must be completed before we go to town.”

“But you go only to get Miss Vernon settled. You must give me your word that you will return to Langford, for we quite expected you to be with us for many weeks longer.”

“I may be obliged to stay on in London to attend to some business of my own. My housekeeper at Portland Place is anxious for some direction as to what I mean to do.”

“Oh, but you need not be in town for that—correspondence will do as well. Or you may send your instructions with Sir James, who goes to town from here. Something very particular must take him to town so early, and that interest will make him happy to oblige you.”

Manwaring viewed the prospect of an engagement between Miss Vernon and Sir James Martin with complaisance. He liked his sister well enough, but he was resigned to the fact that if Maria had not caught Sir James when she was seventeen, eighteen, or nineteen, she could have no hope of him at twenty-two. “And,” he continued, offering Lady Vernon his arm, “if it is money matters, you can leave it all to Charles Vernon, can you not? You are not left as Eliza was, with her fortune in the hands of one who regards her right to it as conditional only, and with no one to come forward and dispute it. Sir Frederick’s intentions were so well known that his brother must abide by them. It is excessively diverting to hear Lady Hamilton talk about Miss Vernon as though she were penniless. To be sure, Miss Vernon’s ten thousand pounds may be nothing when compared to the thirty thousand of her daughters, and I daresay Sir James will not even ask for that, so you will be all the richer! If I had been able to settle ten thousand upon Maria, I would have got her off my hands before now!”

“You have a very happy opinion of my prosperity, and my daughter’s fortune.”

“My opinions can only be drawn from Sir Frederick. Why, the very day we were all a-shooting at Churchill, he spoke of the matter, for Vernon had been trying to coax us both into some speculation. I quite forget what it was, something that involved a great deal of risk, I daresay, for Vernon always had a touch of the gamester about him. I could put nothing into the venture, and Sir Frederick would not and declared that he had learned his lesson from the last scheme and that he must be prudent for Miss Vernon’s sake. It was then that he said he meant to settle as much as ten thousand upon her and very likely more.”

“And was Charles disappointed?”

“I daresay he was—and I confess that I teased him a good deal about what a poor sort of banker he must be! How could he expect to coax strangers out of their money when he could not succeed with his own brother, said I! I am sorry to think what sport I made of him when the day ended so badly, but I understand that Vernon was often at Churchill while Sir Frederick was on the mend, so between them there was no ill feeling. You will not be left at the mercy of one who regards your claims as provisional or who will drag his feet where any money but his own is at stake—a brother will be conscientious out of family feeling.”

“I don’t believe that I ever gave Charles his due in regard to his family feeling,” Lady Vernon replied coolly.

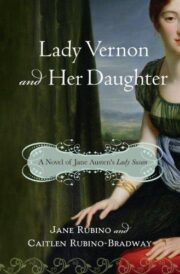

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.