“How can Lady Hamilton think that I decide whether Mr. deCourcy will come and go?” cried Lady Vernon. “I am wholly unacquainted with that young man!”

“They are all of the opinion that you objected to Miss deCourcy’s marriage to Mr. Vernon. Mr. deCourcy feels the insult on his sister’s behalf and so he stays away.”

“He must be a very foolish young man to take such offense at a rumor—and even if it were true that I objected to the Vernons’ marriage, Mr. deCourcy’s affection for Miss Hamilton ought to overrule his resentment against me.”

“Ah, well, his friend Mr. Smith will not be kept away—he takes offense at nothing if there is the promise of diversion.”

When they entered the house, Eliza Manwaring met them with a letter in her hand and proclaimed, with great delight, that they were to have an addition to their party. Lady Vernon supposed that Reginald deCourcy’s affection for his family had overcome his prejudice against her, but to her very great surprise, Eliza announced, “Sir James Martin comes to Taunton on a matter of business, and he will stop at Langford.”

The news affected the ladies very differently. Lady Vernon immediately withdrew to see if she had also received a letter from her cousin; Mrs. Johnson declared that Sir James must have a very particular reason for coming; and Lady Hamilton hurried off to write to her mantua maker, charging her to hurry up Miss Lucy’s white crepe gown, and then summoned the housekeeper to know where she might send for someone to dress Miss Claudia’s hair.

chapter sixteen

When Sir James arrived at Langford, he gave no indication of what interest had brought him from Ealing Park. He received no businesslike correspondence and never rode into town. He would as often sit with the ladies as go shooting with the gentlemen, attending them all with good humor and unfailing gallantry. Toward Lady Vernon, however, he was especially solicitous, and toward Miss Vernon so attentive and gentle that everyone at Langford was persuaded that his purpose in coming was to apply for Miss Vernon’s hand (a rumor started by Alicia Johnson). Having delayed so long until she came of age, Mrs. Johnson assured them all, Sir James was too impatient to wait out the customary term of bereavement and meant to entreat Lady Vernon’s consent to an immediate engagement.

The Hamilton girls and their mother were affronted; the elder girls maintained that Miss Vernon had no conversation, no style, and no fortune, and their mother was contemptuous of Lady Vernon for encouraging the suit when her own husband was not cold in the ground. “I must say, I do not think that she ought to partake of any company at all,” she remarked to Mrs. Manwaring and Mrs. Johnson one evening, after Lady Vernon had retired. “If Lord Hamilton died, I would not allow myself to be seen by anybody but my maid for a twelvemonth!”

“Lady Vernon,” declared Eliza Manwaring, “is the sort of person who will do everything in her own fashion.” She spoke with some bitterness, for Manwaring’s admiration of Lady Vernon had not been overlooked by his wife.

“That sort of fashion, which throws all propriety aside, I do not care for at all!” replied Lady Hamilton. “All of her smiles and leaning upon the family connection will not make Miss Vernon one whit less insipid and dull, nor add a penny to her fortune.” She lowered her voice and glanced toward Frederica Vernon, who sat at the instrument, while the other young people were dancing. “I have heard by way of my niece that Miss Vernon was left only two thousand by her mother’s parents and that Sir Frederick left her nothing at all. That sum might get her a clergyman—and indeed she would suit our Mr. Heywood. He is like to be a widower, as I do not believe that his wife can survive another lying-in, and it would be good to have someone at hand. I cannot bear a single clergyman. But to aim higher! Lady Martin! For Lady Vernon to grasp at that match is the sort of vulgar ambition that I do not like at all.”

Unfortunately, these last remarks were uttered at a break in the music and the pianoforte was near enough to allow Miss Vernon to overhear the latter part of Lady Hamilton’s speech. Her fingers stumbled upon the keys and she rose from the instrument, stammering an apology and begging to be excused. The young ladies pleaded with her to remain, but only for want of a musician. Sir James, fearing that she had been taken ill, went to her side and offered to fetch her some water or wine with great solicitation, which only added to Miss Vernon’s embarrassment.

“How very ill-mannered!” Lady Hamilton declared when Miss Vernon had left the room. “To stop before the young people have had a reel, when she must see how much the gentlemen were enjoying the dancing. Lavinia, my love!” she cried out. “You must sit down and continue the music. She does not play at all badly,” she told the others, “and since her future is settled, she cannot wish for her sisters’ partners.”

Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Manwaring congratulated Lady Hamilton, declaring what a fortunate thing it was for a girl when an early engagement relieved her of the tedious business of accomplishment.

chapter seventeen

Lady Vernon walked out the following morning with Frederica and heard her account of what had been said. “You must not trouble yourself,” she consoled her daughter. “I will not urge you upon Lady Hamilton’s clergyman. She is all presumption and vanity—she is persuaded that no gentleman of fortune can be content without a wife, and therefore marriage must be your cousin’s object. And if James does not court any of her daughters, she concludes that he means to address mine.”

“Yet they have only to look to their own family to see the error of their premise. What of Mr. Lewis deCourcy? He is wealthy and unmarried and as amiable and contented a gentleman as I have ever met.”

“Perhaps the example of Sir Reginald’s marriage persuaded his brother that a good character, an honorable occupation, and the pleasure of never having to give an account of himself to anyone were all the domestic comfort he wished for.”

“And yet,” said Frederica gravely, “a gentleman may seek comfort as readily with vice as with virtue, if he is never called to account for himself.”

“Not every gentleman can enjoy such liberty,” declared a masculine voice. “I must account to Mother for my vices and virtues as rigorously as a cook must account for the spoons.”

Sir James Martin had come up behind them. He stepped between the two ladies and offered an arm to each.

“And what account will you give my aunt for your time at Langford, cousin?” asked Frederica. “I have not seen you attend to anything like business since you arrived.”

“Nonsense, my dear Freddie. I have killed three dozen birds and danced as many dances, and I have read the newspaper every morning and played at billiards in the afternoon and at cards every night. I have admired Miss Claudia’s new spencer and Miss Lucy’s fashion plates and Lady Hamilton’s pug and Mrs. Manwaring’s geraniums. I have written letters to both my mother and my tailor every day. I do not think there is a gentleman at Langford who has been half so industrious.”

“Then perhaps you ought to go back to Ealing Park, where you might recover from your exertions,” declared Lady Vernon.

“I will go today, if you will both come with me.”

“It would please me very much to see my Aunt Martin,” Lady Vernon replied. “But the master of Ealing Park is the sort of deceitful, giddy person that I do not like at all.”

“And what do you say to that, Freddie?” inquired her cousin.

“I do not think that you are deceitful.”

“There!” Sir James laughed. “If a young lady of such sound and analytical mind cannot think me deceitful, then her mother must be mistaken. What is your opinion, Freddie?”

Frederica reflected upon the question. “In science, if our conclusions do not prove true, we must go back to the premise.”

“Very sound! So what is the foundation of your mother’s dis pleasure?”

“I can think of nothing that you have done to offend my mother. I am sure that the great kindness you have shown us both places us greatly in your debt.”

“And what is your reply to that?” Sir James asked Lady Vernon.

“That it is the very notion of indebtedness that offends me” was his cousin’s reply.

“I think that ‘indebtedness’ is a term for business or to be used among strangers,” observed Sir James. “Surely among relations there is only generosity and regard.”

“You did not regard my instructions concerning Vernon Castle. I had asked for advice and assistance, not for alms. I am grateful that it was not more generally known that you were the purchaser,” she added.

“It would have been very ungenerous indeed to have Sir Frederick exposed as the object of his relations’ charity.”

“You asked for assistance in finding a purchaser, which is precisely what I did. You did not ask that you approve the purchaser—you and Sir Frederick gave me leave to manage all. Come, my dear cousin, we must not quarrel. Give me your opinion, Freddie, for you are a very sensible girl. Was I wrong to buy Vernon Castle? If you tell me that I have done wrong, I will beg forgiveness.”

Frederica pondered his question. “I think that you deliberately withheld information from my mother that she ought to have had.”

“There!” Lady Vernon declared.

“But,” her daughter added, “my cousin’s motives were for the best, and he acted out of generosity, so as not to let dear Vernon Castle go to strangers. If he has offended you, I think he ought to have been forgiven.”

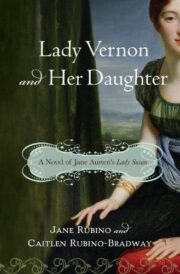

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.