Feel no distress, my dear Catherine, over what is to become of Lady Vernon and her daughter—recall that the house in town will be Lady Vernon’s outright, and that the sum settled upon her at the time of her marriage (to which my brother had added some three thousand pounds) will give her something to live on. If she wants anything more, I am certain that she need only apply to the Martins, as they are very rich.

My sister talks of placing Miss Vernon at school—yet while her education has certainly been neglected, I must think that such a place can do her no good. A temperament that is already weak will only fall prey to the giddy imaginations of those about her, and rather than attaining some measure of education, she will only incur permanent defects in understanding. She would greatly benefit from your example, and might be of some use to you in looking after the children and providing something of companionship to you when I am obliged to be in town. If you are at leisure to write, therefore, I would hope that you will send a few lines to Lady Vernon and encourage her to leave Miss Vernon with us.

Prepare our children for the change that they are to undergo and console your dear parents as far as you can. Sir Reginald and Lady deCourcy will be sorry to see us leave Parklands, but it is only a good day’s journey to Churchill, and when Sir Reginald’s health allows, I have every confidence that they will attempt it.

Our Uncle deCourcy is of the party assembled here, and I took the liberty of giving him your warmest regards, and those of your father and mother.

We shall need to purchase our own silver, as the service used at Churchill, as well as some other effects, were bequeathed to Lady Vernon and I am sure that she will take them away with her when she goes.

Your devoted husband,

Charles Vernon

chapter eleven

The following morning the party assembled at breakfast, but Lady Vernon rose feeling so ill that she was obliged to return to her bed and send Wilson down with apologies to her guests. In their presence, Vernon made a great show of concern and gave orders that everything was to be done to make Lady Vernon comfortable and that the servants need not defer to him before offering her any small amenity or service that her situation warranted. He then expressed his hope that the guests might remain at least long enough to see Lady Vernon once more, but if they were compelled to go sooner, he would convey to his sister-in-law their sincere apologies and regrets. This declaration could only make his company acutely conscious of their host’s desire for them to be off and so they all agreed that orders should be given for their carriages to be ready at two o’clock.

Vernon then went to his sister-in-law’s apartments, where she was sitting with Frederica and Wilson. Frederica avoided his gaze and looked as if she would like to run away, but her mother answered his inquiries after her health with as much composure as she could summon.

He then assured them that they were welcome to remain at Churchill Manor as long as they liked, and they were not to think for a moment that they might be in anybody’s way. Mrs. Vernon would not take it amiss if they were there still when she arrived. “I am certain that your kind friends have all quarreled over who is to take you away, and I know that you will not wish to be in a household with four active children, but if my niece is of the opposite opinion, she is very welcome to remain with us. You find yourself very low now, Frederica, but I think that the company of your cousins and the comfort of familiar surroundings will raise your spirits, will they not?”

Frederica would make no answer, and Lady Vernon replied, “My dear brother, Frederica and I are grateful for your kindness, but it would be too great a sacrifice for me to be deprived of both husband and daughter. I know that Mrs. Vernon, who is said to be the best of mothers, will understand why we would not wish to be separated just now. As for our removal, I do not think that more than two or three weeks will be necessary. I must beg you and Mrs. Vernon for your forbearance until then.”

Vernon did not believe that it was of any consequence to Lady Vernon whether her daughter remained at Churchill or was sent to a school in town. But he bowed and murmured, “Mrs. Vernon and I will always be happy to receive you at Churchill, should you find yourself left with no better place to go,” and took his leave, saying that he must see that all had been made ready for their visitors’ departure.

“My uncle talks as though our visitors leave today!” cried Frederica. “Surely they will remain a week at least! The Clarkes have had a long journey, and it will be very difficult for Mr. deCourcy to return so immediately to Bath.”

Lady Vernon dispatched Wilson to the servants’ quarters, and she returned in a matter of minutes, declaring, “So it is! They are all to leave this afternoon! Mr. Vernon has ordered the carriages for two o’clock.”

Frederica was shocked into silence at her uncle’s selfish inhospitality. Lady Vernon rose immediately. “Help me with my dress, Wilson. I must go down. I hope that they do not hasten their departure on our account. They cannot think that it is we who want them gone.” Quickly submitting to the arranging of her hair and her gown, she accompanied Frederica to the drawing room, where the party had assembled.

Sir James approached as soon as they were seated. “My dear Susan,” he began in a low voice, “my situation here is tenuous, for Vernon wants us gone, and I cannot impose myself upon him. Come away with us to Ealing Park. You may stay as long as you like, and you will not be hurried into a decision as to where you will settle.”

Eliza Manwaring spied a vacant chair beside Sir James and hurried Maria into it. (For she had brought the girl to the unhappy gathering expressly to throw her at the gentleman.) “My dear Lady Vernon, we hope that you and Miss Vernon will come to us at Langford. There may be some sport, but it will keep the men out of the way, and there will be some young people to keep Miss Vernon company. And you may be sure, Sir James, that you and Lady Martin will always be welcome to visit.” Mrs. Manwaring then solicited the support of Mr. Lewis deCourcy, who had drawn his chair up to the group. “Do you not think, sir, that it would be the best plan for Lady Vernon and her daughter to come to Somerset? I am sure that you would not have her open her house in town at this time of year.”

“Indeed, no, but I hope that you, Lady Vernon, and your daughter will give me a share of your time and come to Bath,” replied Mr. deCourcy. “I do nothing but ramble about in that large house upon the Crescent, with a barouche that sits idle while my footman and horses go to fat! The air and the waters would put some roses back into your cheeks, Miss Vernon, and you might help me determine what can be grown in my garden—I can do nothing with it.”

“I thank you for your offer, sir,” murmured Frederica.

“Will you not take a turn with me now?” continued the gentleman as he rose from his chair. “I have heard so much about the forcing gardens at Churchill and the groundsmen give you all the credit for it. I would be very sorry to be off without seeing what you have done. Come, I will take you both,” he added, offering one arm to Frederica and the other to Miss Manwaring. “I do not have the opportunity to parade about with two such elegant young ladies. I am sure that you can indulge an old gentleman for a quarter of an hour.”

The two girls exchanged shy smiles as they allowed themselves to be escorted from the room by Mr. deCourcy.

“My dear Susan, will you let me sit with you for a few minutes?” asked Mrs. Clarke, and Sir James yielded his chair to her and walked over to the window, where he gazed out with a look of sober concentration while Eliza Manwaring endeavored to determine whether Miss Vernon or Miss Manwaring was the object of his attention.

“How much time will it take you to settle your affairs here, my poor Susan?” inquired Mrs. Clarke.

“Much of that will depend upon Mr. and Mrs. Vernon.”

“I hope that you will think of coming to us—you would be put to no expense there, I assure you, and would it not be comforting to be in a place where you and Sir Frederick were once so happy? Unless the business of weddings will give you pain. It seems that neighborliness has done its work, and the sons of Colonel Edwards have asked for our girls. Anne is to marry Phillip and Mary will take Frank, and the Colonel only waits upon the weddings to be off to a more congenial climate, for he is very much afflicted with rheumatism and pleurisy.”

Lady Vernon knew that Colonel Edwards was the gentleman who had purchased Vernon Castle, and Mrs. Clarke had occasionally mentioned him in her letters as a genteel and solicitous neighbor.

“I believe he told Sir James that he means to be gone by January at the very latest, and then—why may Sir James not give Vernon Castle back to you?”

“How can my cousin give me Vernon Castle?” inquired Lady Vernon, puzzled.

“Oh, dear!” cried Mrs. Clarke. “I quite forgot! I was not to speak of it. Mr. Clarke will be so angry! But he knows that he ought not to tell me anything he does not want repeated! Yes, it is all his fault—oh, Mr. Clarke, see what you have done!” she called across the room, which caused that gentleman to duck his head in embarrassment, although he did not know why.

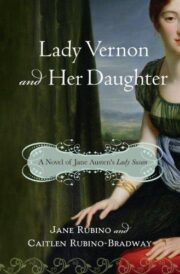

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.