His circuit of the room brought him back to her side. He blew out the taper and speared her with a look. “Will you be fine?”

She liked standing close to him, not only because he wore a pleasant scent, but also because something about his male presence, the grace and strength of it, appealed to her dormant femininity. If all men had his manners, competence, and sheer male beauty, being a woman would be a much more appetizing proposition.

Sophie took her courage in both hands and gazed up at him. “I’d like to hear about those travels, Mr. Charpentier. About the worst memories and best memories, the most beautiful places and the most unappealing. I’ve lived my entire life in the confines of England, and tales of your travels would give my imagination something to keep when you’ve left.”

He studied her for a moment then lifted one hand. Her breath seized in her lungs when she thought—hoped?—he was going to touch her. To touch her cheek or her hair, to lay his palm along her jaw.

He laid his hand over the baby’s head. “If My Lord Baby gives us a peaceful evening, I’ll tell you some of my stories, Miss Sophie. It’s hardly a night for going out on the Town, is it?”

It was better than if he’d touched her, to know he’d give her some tales of his travels, something of his own history and his own memories.

“After you’ve settled in, then. I’ll see you in the parlor downstairs. We’ll see you.”

Except the baby in her arms was seeing nothing at that moment but peaceful, happy baby dreams.

Three

Vim’s little trip through the ducal mansion revealed a few interesting facts about the household. For example, money was not a problem for this particular ducal family.

The servants’ parlor was a comfortable place for furniture, carpets, and curtains that had seen some use, but it was far from shabby. The bathing chamber was a gleaming little space of pipes and marble counters that spoke of both available coin and a willingness to enjoy the fruits of progress.

The main entrance was a testament to somebody’s appreciation for first impressions and appearances. The whole house was gracious, beautiful, and meticulously maintained.

Also festooned with all manner of seasonal decorations, which usually struck Vim as so much wasted effort. Pine boughs quickly wilted and dropped needles all over creation. Clove-studded oranges withered into ugly parodies of their original state. Wreaths soon turned brown, and Christmas trees had to be undecorated as carefully as they were decorated—assuming they didn’t catch fire and set the entire house ablaze.

A lot of bother for nothing, or so he would have said.

But in this house…

He finished his bath and found a clean pair of pajama trousers as well as a clean pair of winter wool socks. Though the vast canopied bed beckoned, Vim instead appropriated a brocade dressing gown from the store in the wardrobe and made his way back through the house to the little servants’ parlor.

He opened the door without knocking and found Miss Sophie within, on her feet, the baby fussing in her arms.

“I don’t know what’s wrong.” Sophie’s voice was laden with concern. “He keeps fussing and fretting but he isn’t… it isn’t his nappy, and he doesn’t want for cuddling. I don’t think he has to settle his stomach either.”

Vim sidled into the room, closing the door behind him. “He’s probably hungry again. Marvelous accommodations upstairs, by the way.” And a marvelously warm silk lining in the dressing gown.

The child quieted at the sound of his voice, turning great blue eyes on Vim. Vim peered down at the baby cradled against Sophie’s middle. “Are you hungry, young Kit, or simply rioting for the fun of it?”

The child slurped on his little left fist.

“Hungry it is. Have you any cold porridge in the kitchen, Miss Sophie?”

“No doubt we do, but he just ate not three hours ago. Are you sure he isn’t sickening for something?”

In those same three hours, Sophie had apparently gone from benevolent stranger to mother-at-large, capable of latching onto every parent’s single worst, most abiding fear.

Vim laid the back of his hand on the baby’s brow. “He’s only yelling-baby-warm, not fevered, so no, I don’t think he’s sickening. Often when they’re coming down with something, they grow a bit lethargic. He’s at the mercy of a very small belly and has to eat more often than he will later in life. This belly here.”

He poked the baby’s middle gently, which provoked a toothless grin.

“Why didn’t I know he’d like that?”

“Likely because you yourself would not react as cheerfully did I make the same overture to you. Why don’t I take him while you hunt him up some tucker? A bit of warm milk to mix the porridge very thin and a baby spoon will get us started.”

Sophie nodded and stepped in close. It took Vim a moment to comprehend that she was handing him the baby, and in that moment, his eyes fell on her hair. Some women thought an elaborate coiffure adorned with jewels and combs and all manner of intricacies would call attention to their beauty.

Others cut their hair short, attempting boyish ringlets and bangs and labeling themselves daring in the name of fashion.

Still others went for a half-tumbled look, presenting themselves as if caught in the act of rising from a bout of thorough lovemaking.

Sophie’s hair was a rich, dark brown, and she wore it pulled back into a tidy bun. For the space of a heartbeat, Vim was close enough to her to study her hair, to admire the simple, sleek curve of it sweeping back from her face to her nape. He could not see any pins or clasps, nothing to secure it in place, and the bun itself was some sort of figure of eight, twisting in on itself without apparent external support.

Which was quietly pretty, a little intriguing, and quite appropriate for Miss Sophie Windham. And if Vim’s fingers itched to undo that prim bun and his eyes longed for the sight of her unbound hair tumbling around her shoulders in intimate disarray, he was gentleman enough to ignore such inconvenient impulses entirely.

“I’ve got him,” Vim said, securing his hands around the baby. “Though I have to say, I think a certain baby has gained weight just since coming home from his outing.”

Sophie’s smile was hesitant. “You like to tease him.”

“He’s a wonderful, jolly baby.” Vim raised the child in his arms so they could touch noses. “Jolly babies are much better company than those other fellows, the ones who shriek and carry on at the drop of a hat.”

His nose was taken prisoner once more, which had been the objective of the exercise.

“I’ll see to the porridge.”

But she’d been smiling as she left the room, which had also been an objective. To be a mother was to worry, but a worried mama made for a worried baby.

“And we cannot have you worrying,” Vim informed the child. “Not like I’m worrying in any case. I was supposed to be at Sidling last week—much as I dread being there this time of year—and there will be hell to pay for my lingering here, though have you chanced a look out the window, My Lord Baby? See all that snow?”

Kit kicked both legs in response and gurgled happily, then slapped his fist back to his mouth.

“I last saw snow like this in Russia. Damned place specializes in cold, dark, snow, and vodka, which explains a lot about the Russian character. And because it’s just us fellows, I need not apologize for my language. Can you say damn? It’s a nice, tame curse, a good place to start. Nobody curses as effectively as a Russian. Nobody.”

And nobody could lament like a Russian either, to the point where Vim had left the country with a sense of relief to be going back to England. Long faces everywhere, sad tales, sad songs, sad prayers, and vodka.

“Nearly drove me to Bedlam, I tell you.”

Africa hadn’t been any better though, nor Tasmania. The Americas were reasonably cheerful places, provided a man didn’t venture too far north or south, nor too far inland.

Kit whimpered and swung his fist toward Vim’s nose again.

“You want your supper or your tea or whatever. Don’t worry, Miss Sophie will be stepping and fetching for you directly. You’re going to be a typical male, relying on the women for all the important things—though you’re a little small yet for that discussion.”

“Mr. Charpentier, are you having a conversation with that child?”

Sophie stood in the doorway, a tray in her hands and her head cocked at a curious angle.

“He won’t learn to speak if all he hears is silence.” Though Vim had to wonder how much Miss Sophie had heard. “Do you want that cat in here?”

An enormous, long-haired black animal was stropping itself against her skirts.

“That’s Elizabeth. He’s earned a little nap by the fire.” The cat continued to bob around her hems, its gait a far cry from a feline’s usual sinuous movement.

“What’s wrong with him?”

She nudged the door closed with her hip and set the tray down on a coffee table. “Nothing is wrong with him; he’s simply missing a front leg. How do we feed that child?”

Indeed, upon closer inspection, under all the hair, the cat was managing on only three legs, and that in addition to the burden of being a tom named Elizabeth. “Let’s use the sofa. I’ll demonstrate, and then you can take over.”

He settled with the baby then waited while Sophie took a seat just a few inches away. The cat—lucky beast—curled himself up against her other hip.

“This is a messy proposition, but it’s all in good fun,” Vim explained. “You can’t load up the spoon with too much—his mouth is quite small, and he’ll manage to get the excess all over creation. You also have to prop him up a bit to help him get the food down rather than up. When he starts batting at the spoon or using the spoon like a catapult, you know he’s through for the time being.”

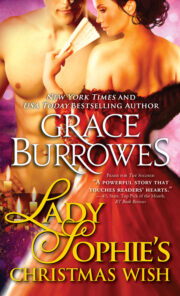

"Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" друзьям в соцсетях.