The lady, for her part, took a sip of her tea, looking not the least discomposed.

“Best eat quickly,” Vim said, settling the child in his arms. “You never know when My Lord Baby will rouse, and then the needs of everyone else can go hang. It was a very good omelet.”

“Is there such a thing as a bad omelet?” She ate daintily but steadily, not even glancing up at him while she spoke.

“Yes, there is, but we won’t discuss it further while you eat.” He resumed his seat across from her, the weight of the baby a warm comfort against his middle. Avis and Alex could both be carrying already, a thought that sent another pang of that unnameable sentiment through him.

“What else can you tell me about caring for Kit, Mr. Char—” She paused and smiled slightly. “Vim. What else can you tell me, Vim?”

“I can tell you it’s fairly simple, Miss Sophie: you feed him when he’s hungry, change him when he’s wet, and cuddle him when he’s fretful.”

She set down her utensils and gazed at the baby. “But how do you tell the difference between hungry and fretful?”

Her expression was so earnest, Vim had to smile. “You cuddle him, and if his fussing subsides, then he wasn’t hungry, he was just lonely. If he keeps fussing, you offer him some nourishment, and so on. He’ll tell you what’s amiss.”

“But that other business, at the coaching inn. You knew he was uncomfortable, and to me it wasn’t in the least obvious what the trouble was.”

“And now you know he needs to be burped when he’s filled his tummy. Your tea will get cold.”

She took a sip, but he didn’t think she tasted it, so fixed was she on the mystery of communicating with a baby. She continued to pepper him with questions as she finished her meal and tended to the dishes, not untying her apron until the kitchen was once again spotless.

By that point, Vim had been making slow circuits of the kitchen with the child in his arms. He had less than an hour of light left, and it really was time to be going.

“I thank you for the meal, Miss Sophie, and I will recall your cooking with fondness as I continue my travels. If you’ll take Kit, I’ll fetch my coat from the parlor and wish you good day.”

He passed her the baby, making very sure that this time his hand came nowhere near her person.

He was leaving.

This realization provoked something close to panic in Sophie’s usually composed mind. She told herself she was merely concerned for the baby, being left in the care of a woman who had still—still!—never changed a single nappy.

But there was a little more to it than that. More she was not about to dwell on. Mature women of nearly seven-and-twenty did not need to belabor the obvious when they fell prey to unbecoming infatuations and fancies.

“I wish you’d stay.” The words were out before she could censor herself.

“I beg your pardon?” He paused in the act of rolling his cuffs down muscular forearms dusted with sandy, golden hair. How could a man have beautiful forearms?

She bent her head to kiss the baby on his soft, fuzzy little crown. “I have no notion how to go on with this child, Mr. Charpentier, and those old fellows in the carriage house likely have even less. I realize I ought not to ask it of you, but I am quite alone in this house.”

“Which is the very reason I cannot stay, madam. Surely you comprehend that?”

He spoke gently, quietly, and Sophie understood the point he was making. Gentlemen and ladies never stayed under the same roof unchaperoned.

Except with him—with Vim Charpentier—she wasn’t Lady Sophia Windham. She’d made that decision at the coaching inn, where announcing her titled status would have served no point except to get her pocket picked. Higgins was old enough to address her as Miss Sophie, and being Miss Sophie was proving oddly appealing. A housekeeper or companion could be Miss Sophie; a duke’s daughter could not.

“This weather will be making all manner of strange bedfellows, Mr. Charpentier. And if we’re alone, who is to know if propriety hasn’t been strictly observed?”

“This is not a good idea, Miss Windham.”

“Going out in that storm is a better idea?”

She let the question dangle between his gentlemanly concerns about propriety and the commonsense needs of a woman newly burdened with a small baby. When he turned to stand near the window, Sophie sent up a little prayer that common sense was going win out over gentlemanly scruples. The baby whimpered in his sleep, which had Mr. Charpentier sending her a thoughtful look.

“I can stay, but just for one night, and I’ll be off at first light. There is some urgency about the balance of my journey.”

“Thank you. Kit and I both thank you.” She had the oddest urge to kiss his cheek.

She kissed the baby instead. “Come along, and I can show you to a guest room.”

He retrieved his haversack from the back hallway and followed along behind her, a big, silent presence. She could feel him taking in the trappings of a duke’s Town residence but hoped he saw the little things that made it a home too.

The servants had decorated before leaving for the season—pine boughs scented the mantels, red ribbons decorated tall beeswax candles that would have been lit at the New Year and on Twelfth Night were the family in residence. Cinnamon sachets and clove-studded oranges hung in the hallways, and wreaths graced the windows facing the street.

“Their Graces must take their holidays seriously,” Mr. Charpentier observed. “Is that a Christmas tree?”

Sophie paused outside the half-open door of one of the smaller parlors. “Her Grace’s mother was German, like much of the old king’s court. The Christmas trees were originally for Oma, so she wouldn’t be as lonely for her homeland.”

She wondered what he’d say if he knew he was peering around at a duchess’s personal sitting room. Mama served her daughters and sons tea and scoldings in this room, also wisdom, sympathy, and love.

Always love.

Sophie stood for a moment, the baby cradled on her shoulder, Mr. Charpentier close by her side in the doorway. She was going to associate bergamot with this moment for a long while to come, the first time she’d shown a visitor of her own around the house—a visitor of hers and Kit’s.

She waited for Vim to step back then continued their progress. “Your room is on the first floor. The servants’ stair goes right to the back hallway, though the main staircase is the prettier route.”

She took him through the front entrance with its presentation staircase of carved oak. The whole foyer was a forest of polished wood—the walls and ceiling both paneled, the banisters lathe turned, and half columns with fanciful pediments and capitals standing in each corner of the octagonal space. The wood was maintained with such a high shine of beeswax and lemon oil that sunny days saw more light bouncing around the foyer than in practically any other part of the house.

“I take it Their Graces entertain a fair amount?” He was coming up the stairs behind her, as a gentleman would.

“His Grace is quite active in the Lords, so yes.”

“And Her Grace?”

“She keeps her hand in. They also have the occasional summer house party at the family seat. This room ought to serve for the night.”

She’d taken him not to a guest room but to her brother Valentine’s old room in the family wing. The wood box would be full, the coal bucket filled, a fire laid, and the bed made up in anticipation of his lordship’s visit to Town to collect his sister.

“I’m sorry it’s so chilly. I’ll bring you up some water for the room. Let me show you the bathing chamber. As far as I know, the fire under the boiler should still have some coals.”

The bathing chamber was across the hall, a renovated dressing room having had the ideal location between cisterns and chimneys.

“This is quite modern,” Mr. Charpentier said. “You’re sure Their Graces would not mind your sharing such accommodations with a virtual stranger?”

They’d mind. They wouldn’t begrudge him the best comforts the mansion could offer, but they’d mind mightily that he had Sophie’s exclusive company.

“A duke’s household doesn’t skimp on hospitality, Mr. Charpentier, though by rights we should be providing you a valet and footmen to step and fetch.”

“I’m used to doing for myself, though where will I find you should the need arise?”

“I’m just down the hallway, last door on the right.”

And it was time to leave him, but she hesitated, casting around for something more to say. The idea of spending another long, cold evening reading by firelight seemed like a criminal waste when she could be sharing those hours with Mr. Charpentier. The baby let out a little sigh in her arms, maybe an indication of some happy baby dream—or her own unfulfilled wishes.

“Shall I bring the cradle up from the servants’ parlor, Miss Sophie?”

The cradle?

“Yes. The cradle. That would be helpful. I suppose I should get some nappies from the laundry and clean dresses and so forth.”

He smiled, as if he knew her mind had gone somewhere besides the need to care for the baby, but he said nothing. Just set his bag down, went to the hearth to light the fire, and left Sophie standing in the door with the child cradled in her arms.

“You’ll find your way to the bathing chamber if you need it?”

He rose and began using a taper to add candlelight to the meager gloom coming from the windows. “I’ve made do with so much less than you’re offering me, Miss Sophie. Travel makes a man realize what little he needs to be comfortable and how easily he can mistake a mere want for a need. I’ll be fine.”

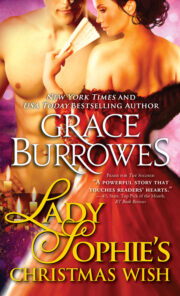

"Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" друзьям в соцсетях.