“No, no, ma’am!” he said soothingly. “Merely a touch of influenza! I shall send you a saline draught, and you will very soon be more comfortable. I’ll look in tomorrow, to see how you go on. Meanwhile, you must stay quietly in your bed, and do as Miss Wychwood bids you.”

He then went out of the room with Annis, told her that there was no reason for her to be anxious, gave her some instructions, and, when he took his leave, looked rather narrowly at her, and said: “Now, don’t wear yourself out, ma’am, will you? You don’t look to be in such good point as when I saw you last: I suspect you have been trotting too hard!”

When Annis returned to the sickroom, she found Miss Farlow in a state of tearful agitation, the reason for this fresh flow of tears being her fear that poor little Tom might have taken the disease from her, for which she would never, never forgive herself.

“My dear Maria, it will be time enough to cry about it if he does contract influenza, which very likely he won’t,” said Annis cheerfully. “Betty will be bringing you some lemonade directly, and perhaps when you have drunk a little of it you will be able to go to sleep.”

But it soon became plain that Miss Farlow was not going to be an easy patient. She begged Miss Wychwood not to give her a thought, but to go away and on no account to feel she must stay at her side, because she had everything she wanted, and she couldn’t bear to be giving her so much trouble; but if Miss Wychwood absented herself for more than half-an-hour she fell into sad woe, because this showed her that nobody cared what became of her, least of all her dear Annis.

Lady Wychwood and Lucilla were both anxious to share the task of nursing Miss Farlow, but Annis would not permit either of them to go into the sickroom. Lucilla looked decidedly relieved, for she had never nursed anyone in her life, and was secretly scared that she might do the wrong things; and Lady Wychwood, when it was pointed out to her that she had her children to consider and owed it to them not to expose herself to the risk of infection, agreed reluctantly to stay away from Poor Maria. “But you must promise me to take care of yourself, Annis! You must let Jurby help you, and you mustn’t linger in the room, or approach Maria too closely! How shocking it would be if you were to become ill!”

“Very shocking—and very surprising too!” said Annis. “You know I am never ill! You can’t have forgotten all the occasions when an epidemic cold has laid everyone at Twynham low, except Nurse and me! If you will look after Lucilla for me I shall be very much obliged to you!”

Jurby, when asked if she would help to nurse Miss Farlow, said that Miss Annis might leave it entirely to her, and not bother her head any more; but as she apparently believed that Miss Farlow had contracted influenza on purpose to set them all by the ears Annis took care always to be at hand when she stalked into the room to measure out a dose of medicine, wash Miss Farlow’s face and hands, or shake up her pillows. Jurby disliked Miss Farlow, thought that she could be better if she wished, and in general behaved as if she had been a gaoler in charge of a troublesome prisoner. Miss Wychwood remonstrated with her in vain. “I’ve no patience with her, miss, making such a rout about nothing more than the influenza! Anyone would think she was in a confirmed consumption to hear the way she talks about her aches and ills! What’s more, Miss Annis, it puts me all on end when she says she don’t want you to be troubled with her, or to sit with her, and the next minute wonders what’s become of you, and why you haven’t been next or nigh her for hours!”

“Oh, Jurby, pray hush!” begged Miss Wychwood. “I know she—she is being tiresome, but one must remember that influenza does make people feel very ill so that it is no wonder she should be in—in rather bad skin! But you won’t have to bear with her for much longer, I hope: Dr Tidmarsh has told me that he sees no reason why she should not get up out of her bed for a little while tomorrow, and I think it will vastly improve her spirits if she does so, because it is what she has been wanting to do from the outset.”

Jurby gave a snort of disbelief, and said darkly: “That’s what she says,Miss Annis, but it’s my belief we shan’t see her out of her bed for a sennight!”

But in this prophecy she wronged Miss Farlow. Permitted to sit up in an armchair for an hour or two on the following day, her spirits revived; she began to enumerate all the tasks which she had been obliged to leave undone; and announced her conviction that by the next day she would be stout enough to resume all her duties; so that Miss Wychwood had difficulty in dissuading her from setting to work immediately on the careful darning of a damaged sheet. Fortunately, she discovered herself to be so sadly weakened by her brief but severe attack that after the exertion of dressing her hair she was glad to sit quietly in her armchair, with one shawl round her shoulders and another spread over her legs, and to engage in no more strenuous occupation than that of reading the Court News in the Morning Post.

However, she was certainly on the mend, and Miss Wychwood, in spite of feeling unaccountably exhausted, was looking forward to a period of calm when she received from Jurby, as that stern handmaid drew back the curtains from round her bed on the following morning, the sinister tidings that Nurse wished to have Dr Tidmarsh summoned to take a look at Master Tom.

Thus rudely awakened, Miss Wychwood sat up with a jerk, and said in horrified accents: “Oh, Jurby, no! You can’t mean that he has got the influenza?”

“There isn’t a doubt of it, miss,” said Jurby implacably. “Nurse suspicioned he was sickening for it last night, but she had the sense to take the baby’s crib into the dressing-room, so we must hope the poor little innocent won’t have caught the infection from Master Tom.”

“Indeed we must!” said Annis, flinging back the blankets, and sliding out of bed. “Help me to dress quickly, Jurby! I must send a message to Dr Tidmarsh at once, and warn Wardlow to lay in a stock of lemons, and some more pearl barley, and chickens for broth, and—oh, I don’t know, but no doubt she will!”

“You may be sure she will, miss; and as for the doctor, her ladyship sent down a message to him the instant Nurse told her Master Tom was taken ill. Of course,” she added gloomily, as she handed her stockings to Miss Wychwood, “the next thing we shall know is that her ladyship has caught the infection. Then we shall be in the suds!”

“Oh, pray don’t say so, Jurby!” begged Miss Wychwood.

“I shouldn’t be doing my duty by you, miss, if I didn’t warn you. In my experience, if you get one trouble coming on you which you didn’t expect you may look to get two more.”

Miss Wychwood might smile at this oracular pronouncement, but it was in a mood of considerable dismay that she went down, some minutes later, to the breakfast-parlour. Here she found Lady Wychwood eating bread-and-butter, with her infant daughter in her lap, and Lucilla watching this domestic picture with a kind of awed fascination. Miss Wychwood, knowing how anxious her sister-in-law was inclined to be whenever anything ailed her children, was much relieved to see her looking so calm. She said, as she bent to kiss her: “I am so sorry, Amabel, to hear that Tom is now a victim of this horrid influenza!”

“Yes, it is most unfortunate,” agreed her ladyship, sighing faintly. “But not unexpected! I thought he would be bound to take it from Maria, for she had been playing with him the very day she began to feel unwell. But Nurse doesn’t think it will prove to be a bad attack, and I am persuaded I may have complete faith in Dr Tidmarsh. I formed the opinion, when I was talking to him the other day, that he is a perfectly competent person, which, of course, one would expect a Bath doctor to be. The worst of it is,” she added, her eyes filling with tears, and her lips trembling a little, “that I must not take care of Tom myself. Whenever he has been ill he has always called for Mama,and never have I left him for more than a minute! However, I do see that it’s my duty to keep Baby out of the way of the infection, and I don’t mean to be silly about it. I have talked it over with Nurse, and we are agreed that she is to look after Tom, and I am to have sole charge of Baby. Which I shall like very much, shan’t I, my precious?”

Miss Susan Wychwood, who had been chortling to herself, responded to this by uttering a series of unintelligible remarks, which her mama interpreted as signifying agreement; and blew several bubbles.

“What a clever girl!” said Lady Wychwood, in a voice of doting fondness.

When the doctor arrived, he confirmed Nurse’s diagnosis; warned Lady Wychwood that Tom was unlikely to make such a quick recovery as Miss Farlow’s had been; and told her that she must not worry if he was still inclined to be feverish at the end of a sennight, because it was often so with obstreperous little boys whom it was almost impossible to keep quietly in their beds, since the instant their aches and pains subsided it was one person’s work—or, perhaps it would be more accurate to say two persons’ work, to prevent them from bouncing about, and even getting out of bed the instant one took one’s eye off them. “I have two little rascals of my own, my lady!” he told her, with ill-concealed pride. “Just such bits of quicksilver as your boy is, so you may believe I don’t speak without personal experience!” He then told her that she was very wise to preserve her baby from any risk of infection; complimented her on Miss Susan Wychwood’s sturdy limbs and powerful lungs; and went off leaving her to inform Annis that he was quite the most agreeable and sympathetic doctor she had ever known.

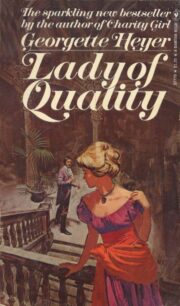

"Lady of Quality" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Quality". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Quality" друзьям в соцсетях.