“There’s one that has more hair than wit, and a mouthful of pap besides,” Jurby said grimly. “It’s a good thing I didn’t go to bed myself, which I never meant to do, not for a moment, for I guessed she’d come fretting you to death! As though you hadn’t had enough trouble this day!”

“Oh, Jurby, hush! You shouldn’t speak of her like that!” said Annis weakly.

“Nor I wouldn’t to anyone but you, miss, but it’s coming to something, after all the years I’ve looked after you, if I can’t speak my mind to you. Next you’ll be telling me I’d no right to send her packing!”

“No, I shan’t,” sighed Annis. “I’m too thankful to you for having rescued me! I haven’t had anything to trouble me, but from some cause or another I’m out of temper—probably because my accounts wouldn’t come right!”

“And probably for quite another reason, miss!” said Jurby. “I haven’t said anything, and nor I don’t mean to, for you know your own business best.” She tucked in the blankets, and began to draw the curtains round the bed. “Which isn’t to say I don’t know which way the wind is blowing, for I’m not a cabbage-head, and I haven’t lived next and nigh you ever since the day you came out of the nursery without getting to know you better than you think, Miss Annis! Now, you shut your eyes, and go to sleep!”

Miss Wychwood was left wondering how many members of her domestic staff also knew which way the wind was blowing; and fell asleep wishing that she did know her own business best.

The night brought no counsel, but it did restore her to something not too far removed from her usual cheerful calm, and enabled her to support with creditable equanimity the spate of conversation which enlivened (or made hideous) the breakfast-table. For this, Lucilla and Miss Farlow were responsible, Miss Farlow being determined to show that she bore Lucilla no ill-will by chatting to her in a very sprightly way, and Lucilla being anxious to atone for her pert back-answer, by responding to these amiable overtures with equal amiability and the appearance of great interest.

In the middle of one of Miss Farlow’s reminiscent anecdotes, a note addressed to Lucilla was brought in by James, who told her that Mrs Stinchcombe’s man had been instructed to wait for an answer. It had been written in haste by Corisande, and no sooner had Lucilla read it than she gave a squeak of delight, and turned eagerly to Miss Wychwood. “Oh, ma’am, Corisande invites me to join a riding-party to Badminton! May I do so? Pray don’t say I mustn’t! I won’t tease you—but I want to visit Badminton above all places, and Mrs Stinchcombe sees no objection to die scheme, and it is such a fine day—”

“Stop, stop!” begged Miss Wychwood, laughing at her. “Who am I to object to what Mrs Stinchcombe approves of? Of course you may go, goose! Who is to be of your party?”

Lucilla jumped up, and ran round the table to embrace her. “Oh, thank you, dear, dear Miss Wychwood!” she said ecstatically. “And will you send someone down to the stables to desire them to bring Lovely Lady up to the house immediately? Corisande writes that if I am permitted to join the party they will pick me up here, on the way, you know! It is Mr Beckenham’s party, and Corisande says there will be no more than six of us: just her, and me, and Miss Tenbury, and Ninian, and Mr Hawkesbury! Besides Mr Beckenham himself, of course.”

“Unexceptionable!” said Miss Wychwood, with becoming gravity.

“I made sure you would say so! And I think Mr Beckenham is one of the most obliging people imaginable! Only fancy, ma’am! He arranged this expedition merely because he heard me telling someone in the Pump Room yesterday—I forgot who it was, and it doesn’t signify!—that I had not visited Badminton, but hoped very much to do so. And the best of it is,” she added exultantly, “that he will be able to take us inside the house, even if this doesn’t chance to be a day when it is open to visitors, because he has frequently been staying there, being a friend of Lord Worcester’s, Corisande says!”

She then sped away to hurry into her riding-habit, and before she reappeared Ninian arrived in Camden Place, and, leaving James to take charge of his borrowed hack, came in to tell Miss Wychwood that although he did not above half wish to join Mr Beckenham’s party he had consented to do so because he thought it his duty to see that Lucilla came to no harm. “Which I thought you would wish to be assured of, ma’am!” he said grandly.

It was difficult to imagine what possible harm could threaten Lucilla in such elegant company, but Miss Wychwood thanked him, said that she could now be easy, and that she hoped he would contrive to derive some enjoyment from the expedition. She was perfectly aware that he regarded Harry Beckenham with a jealous eye; and guessed, shrewdly, that seeing Lucilla came to no harm was his excuse for accepting an invitation too tempting to be refused. The guess became a certainty when he said, in an off-hand way: “Oh, well, yes! I daresay I shall! I own, I should like to get a glimpse of the Heythrop country! And it isn’t everyone who gets the chance to see the house in a private way, so it would be a pity to miss it. I believe it is very well worth a visit!”

Miss Wychwood agreed to this, without the glimmer of a smile to betray her amusement at the instant picture this airy speech conjured up of young Mr Elmore’s dazzling his family and his acquaintances with casual references to the elegance and the various amenities of a ducal seat, which he had happened to visit, quite privately, of course, during his sojourn at Bath.

She saw the party off, a few minutes later, confident that Mr Carleton in his most censorious mood would be hard put to it to find fault with her for having done so. And if he did find fault with her, she would take great pleasure in reminding him that when he had so abruptly left her rout-party he had said that since Ninian and Harry Beckenham were taking good care of Lucilla there was no need for him to keep an eye on her.

The rest of the morning passed without incident, but shortly after Lady Wychwood had retired for her customary rest, Miss Wychwood, again wrestling with accounts in her book-room, received a most unexpected visitor.

“A Lady Iverley has called to see you, miss,” said Limbury, proffering a salver, on which lay a visiting-card. “I understand she is Mr Elmore’s respected parent, so I have conducted her to the drawing-room, feeling that you would not wish me to say you was not at home.”

“Lady Iverley?” exclaimed Miss Wychwood. “What in the world—No, of course I don’t wish you to tell her I’m not at home! I will come up directly!”

She thrust her accounts aside, satisfied herself, by a brief glance at the antique mirror which hung above the fireplace that her hair was perfectly tidy, and mounted the stairs to the drawing-room.

Here she was confronted by a willowy lady dressed in a clinging robe of lavender silk, and a heavily veiled hat. The gown had a demi-train, a shawl drooped from Lady Iverley’s shoulders, and a reticule from her hand. Even the ostrich plumes in her hat drooped, and there was a strong suggestion of drooping in her carriage.

Miss Wychwood came towards her, saying, with a friendly smile: “Lady Iverley? How do you do?”

Lady Iverley put back her veil, and revealed to her hostess the face of a haggard beauty, dominated by a pair of huge, deeply sunken eyes. “Are you Miss Wychwood?” she asked, anxiously staring at Annis.

“Yes, ma’am,” replied Annis. “And you, I fancy, are Ninian’s mama. I am very happy to make your acquaintance.”

“I knew it!” declared her ladyship throbbingly. “Alas, alas!”

“I beg your pardon?” said Annis, considerably startled.

“You are so beautiful!” said Lady Iverley, covering her face with her gloved hands.

An alarming suspicion that she was entertaining a lunatic crossed Miss Wychwood’s mind. She said, in what she hoped was a soothing voice: “I am afraid you are not quite well, ma’am; pray won’t you be seated? Can I do anything for you? A—a glass of water, perhaps, or—or some tea?”

Lady Iverley reared up her head, and straightened her sagging shoulders. Her hands fell, her eyes flashed, and she uttered, in impassioned accents: “Yes, Miss Wychwood! You may give me back my son!”

“Give you back your son?” said Miss Wychwood blankly.

“You cannot be expected to enter into a mother’s feelings, but surely, surely you cannot be so heartless as to remain deaf to her pleadings!”

Miss Wychwood now realized that she was not entertaining a lunatic, but a lady of exaggerated sensibility, and a marked predilection for melodrama. She had never any sympathy for persons who indulged in such ridiculous displays: she considered Lady Iverley to be both stupid and lacking in conduct; but she tried to conceal her contempt, and said kindly: “I collect that you are labouring under a misapprehension, ma’am. Let me hasten to assure you that Ninian isn’t in Bath on my account! Do you imagine him to be in love with me? He would stare to hear you say so! Good God, he regards me in the light of an aunt!”

“Do you take me for a fool?” demanded her ladyship. “If I had not seen you, I might have been deceived into believing you, but I have seen you, and it is very plain to me that you have ensnared him with your fatal beauty!”

“Oh, fiddle!” said Miss Wychwood, exasperated. “Ensnared him, indeed! I make all allowances for a parent’s partiality, but of what interest do you imagine a green boy of Ninian’s age can possibly be to me? As for his having fallen a victim to my fatal beauty,as you choose to call it, such a notion has never, I am very sure, entered his head! Now, do, pray, sit down, and try to calm yourself!”

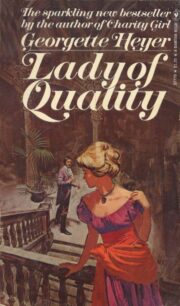

"Lady of Quality" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Quality". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Quality" друзьям в соцсетях.