She gave a choke of laughter. “I didn’t mean that! You know I didn’t! Of course, if you had a title it would be perfectly proper to call you by it, but only think what my aunt would say if she heard me calling you Oliver!”

“As it seems unlikely that she will hear it, that need not trouble you,” he said. “If you have any qualms, allay them with the reflection that Princess Charlotte addresses all her uncles—and, for anything I know, her aunts too—by their Christian names, and even the youngest of them is older than I am!”

Lucilla had little interest in Royalty and dismissed the Princess Charlotte summarily. “Oh, well, I daresay things are different for princesses!” she said. “But you said that it’s unlikely my aunt will ever hear me call you Oliver. W-what do you mean, Unc—sir?”

“I understand that she has washed her hands of you?”

“Yes!” breathed Lucilla, clasping her hands together, and keeping her eyes fixed on his face. “And so—?”

“It behoves me, of course, to find some other female willing to take charge of you.”

Her face fell. “But when am I to make my come-out?”

“Next year,” he replied.

“Next year? Oh, that’s too bad of you!” she cried. “I shall be past eighteen by then, and almost on the shelf! I want to come out this year!”

“I daresay, but it won’t harm you to wait for another year,” he answered unfeelingly. “In any event, you must, because Julia Trevisian, who is to present you at one of the Drawing-rooms, cannot undertake the very exhausting task of chaperoning you to all the functions to which she will see to it that you are invited, until your cousin Marianne is off her hands. Marianne is to be married in May, midway through the Season, and that would be far too late for you to make your first appearance—even if Julia were not, by that time, wholly done-up, which, from her conversation when I last saw her, I gather she expects to be.”

“Is Cousin Julia going to bring me out?” she asked, brightening perceptibly. “Well, I must say that if you arranged that, sir, it is quite the best thing you’ve ever done for me! In fact, it is the only good thing you’ve ever done for me, and I am truly grateful to you!”

“Handsomely said!”

“Yes, but it doesn’t settle the question of where I am to live, or what I am to do for a whole year,” she pointed out. “And I wish to make it plain to you that nothing—nothing!—will prevail upon me to return to Aunt Clara! If you force me to go back, I shall run away again!”

“Not if you have a particle of commonsense,” he said dryly. He looked her over, rather sardonically smiling. “You’ll do as you are bid, my girl, for if I have any more highty-tighty behaviour from you I promise you I shan’t permit you to come out next Season.”

She turned white with sheer rage, and stammered: “You—you—”

“Enough of this folly!” interposed Miss Wychwood, in blighting accents. “You are both talking arrant nonsense! I don’t know which of you is being the more childish, but I know which of you has the least excuse for behaving like a spoilt baby!”

A tinge of colour stole into Mr Carleton’s cheeks, but he shrugged, and said, with a short laugh: “I’ve no patience to waste on pert and disobedient schoolgirls.”

“I hate you!” said Lucilla, in a low and trembling voice.

“I daresay you do.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake come out of the mops, both of you!” said Miss Wychwood, quite exasperated. “This ridiculous quarrel has sprung up for no reason at all! There can be no question of your uncle’s sending you back to Mrs Amber, Lucilla, because she has made it abundantly clear that she doesn’t want you back.”

“She will change her mind,” said Lucilla despairingly. “She frequently says she washes her hands of me, but she never does so!”

“Well, it’s my belief your uncle wouldn’t send you to her even if she does change her mind.” She raised a quizzical eyebrow at Mr Carleton, and said: “Would you, sir?”

A reluctant smile just touched his lips. “As a matter of fact, no: I wouldn’t,” he admitted. “She seems to me to have exercised no control over Lucilla, and is demonstrably not a fit or proper person to have charge of her. So I am now faced with the unenviable task of finding another, and, it is to be hoped, a more resolute member of the family to fill her place.”

Very little of this speech gratified Lucilla, but she was so much relieved by the discovery that he had no intention of restoring her to Mrs Amber that she decided to ignore such parts of it which had grossly offended her. She said tentatively: “Wouldn’t it be possible for me to remain in my dear Miss Wychwood’s charge, sir?”

“No,” he replied uncompromisingly.

She choked back an unwise retort. “Pray tell me why not!” she begged.

“Because, in the first place, she is even less a fit and proper person to act as your guardian than is your aunt, being far too young to chaperon you, or anyone else, and wholly unrelated to you.”

“She is not too young!” cried Lucilla indignantly. “She is quite old!”

“... and in the second place,” he continued, betraying only by a quiver of the muscles beside his mouth that he had heard this hot interjection, “it would be the height of impropriety for me—or, indeed, you!—to impose so outrageously on her good nature.”

It was evident that this aspect had not previously occurred to Lucilla. She took a moment or two to digest it, and said, finally: “Oh! I hadn’t thought of that.” She looked imploringly at Miss Wychwood, and said: “I wouldn’t—I wouldn’t for the world impose on you, ma’am, but—but should I be an imposition? Pray tell me!”

Throwing a fulminating glance at Mr Carleton, Miss Wychwood replied: “No, but one of the objections your uncle has raised I realize to be just. I am not related to you, and it would be thought very odd if you were to be known to have been removed from Mrs Amber’s care, and put into mine. Such an extraordinary change must give rise to conjecture, and a great deal of poker-talk which I am persuaded you wouldn’t relish. Moreover, that sort of scandalbroth must inevitably reflect on Mrs Amber, and that, I know, you wouldn’t wish to happen. For however many tiresome restrictions she has subjected you to, and however boring you found them, you must surely acknowledge that she has acted always—however mistakenly—with nothing but your welfare in mind.”

“Yes,” Lucilla agreed reluctantly. “But not when she tried to make me accept an offer from Ninian!”

This, as Mr Carleton, cynically appreciative of this exchange, recognized to be (in his own phraseology) a leveller, did not prove to be a home-hit. Miss Wychwood rallied swiftly, and said: “I shouldn’t wonder at it if she thought she was promoting your welfare. Recollect, my love, that Ninian was quite your best friend when you were children! Mrs Amber may well have thought that you would find true happiness with him.”

“Are you—you, ma’am!—trying to persuade me to go back to Cheltenham?” Lucilla demanded, in sharp suspicion.

“Oh, no!” replied Miss Wychwood calmly. “I don’t think that would answer. What I am trying to do is to point out to you that if you, by some unlikely chance, could prevail upon your uncle to appoint me to be your guardian, in preference to any of your own relations, we should all three of us come under the gravest censure. Well, I shan’t attempt to conceal that I have no wish to incur such censure; and, in your case, it would be extremely damaging, for you may depend upon it that Mrs Amber would inform every one of her friends and acquaintances—and probably your paternal relatives as well—that you were quite beyond her control, and had left her to reside with a complete stranger, which—”

“.. . would have the merit of being true!” interpolated Mr Carleton.

“Which,” pursued Miss Wychwood, ignoring this unmannerly interruption, “would have a far more damaging effect on your future than you are yet aware of. Believe me, Lucilla, nothing is more fatal to a girl than to have earned (however unjustly) the reputation of being a hurly-burly female, wild to a fault, and so hot-at-hand as to be ready to tie her garter in public rather than to submit to authority.”

“That would be very bad, wouldn’t it?” said Lucilla, forcibly struck by this masterly representation of the evils attached to her situation.

“It would indeed,” Miss Wychwood assured her. “And it is why I am strongly of the opinion that your uncle should make arrangements for you to reside, until your come-out, with some other of your relations—preferably one who lives in London, and is in a position to introduce you into the proper ways of conducting yourself in Society before you actually enter it. He is the only member of your father’s family with whom I am acquainted, but I should suppose that he is not the only representative of it.” She turned her head, to direct a look of bland enquiry at Mr Carleton, and said: “Tell me, sir, has Lucilla no aunts or cousins, on your side of the family, with whom it would be quite unexceptionable for her to reside?”

“Well, there is my sister, of course,” he said thoughtfully.

“My Aunt Caroline?” said Lucilla, doubtfully. “But isn’t she a great invalid, sir?”

“Yes, being burnt to the socket is her favourite pastime,” he agreed. “She suffers from a mysterious complaint, undiscoverable, but apparently past cure. One of its strangest symptoms is to put her quite out of frame whenever she finds herself asked to do anything she doesn’t wish to do. She has been known to become prostrate at the mere thought of being obliged to attend some party which promised to be a very boring function. There’s no saying that she wouldn’t sink into a deep decline if I were to suggest to her that she should take charge of you, so I shan’t do it. I can’t have her death laid at my door.”

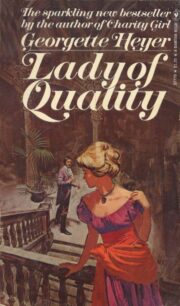

"Lady of Quality" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Quality". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Quality" друзьям в соцсетях.