He had listened to her in staring silence, and he did not immediately answer her. But after a moment or two, he pronounced in pompous accents that he was no advocate for the license granted to the modern generation. Embroidering this theme, he said: “I hold that parents must be the best judges of such matters. They must, of necessity, know better than their children—”

“Fiddle!” said Miss Wychwood, bringing this dissertation to a summary closure. “Did Papa arrange your marriage to Amabel?” She saw that she had discomfited him, and added, with her lovely smile: “Trying it on too rare and thick, Geoffrey! You fell in love with Amabel, and proposed to her before Papa had ever set eyes on her! Didn’t you?”

He flushed darkly, tried to meet the challenge in her eyes, looked away, and replied, with a sheepish grin: “Well—yes! But,” he said, making another recover, “I knew Papa would approve of my choice, and he did!”

“To be sure he did!” agreed Miss Wychwood affably. “And if he had not approved of it, no doubt you would have cried off, and offered for a lady he did approve of!”

“I should have done no such thing!” he declared hotly. He met her laughing eyes, seethed impotently for a moment, and then capitulated, saying in the voice of one goaded to extremity: “Oh, damn you, Annis! My case was—was different!”

“Of course it was!” she said, patting his hand. “No one in the possession of his senses could have raised the least objection to your marriage to Amabel!”

His hand, turning under hers, grasped it warmly, and he said, with all the embarrassment of an inarticulate man: “She—she is past price, Annis—isn’t she?”

She nodded, dropped a light kiss on his brow, and said: “Indeed she is! Now, in a little while you will see Lucilla for yourself: Maria is going to go with her, and Ninian, to the theatre this evening, which will leave us to enjoy a comfortable cose.”

He blinked at her. “What, is the young man here too?”

“Yes, he is putting up at the Pelican, but he will be here to dine with us.”

“I don’t understand any of it!” he complained.

“No, it’s the most absurd situation,” she agreed mischievously. “And the cream of the jest is that now no one is trying to prevail upon them to become engaged they are going on together perfectly harmoniously—except, of course, for a few breezes! Schoolroom stuff!”

She went away then, to change her walking habit for an evening gown, and when she returned she brought Lucilla with her. Lucilla was looking very pretty and very youthful, and when she curtsied, and said how-do-you-do, with her enchantingly shy smile, Sir Geoffrey’s disapproving expression relaxed a little, and by the time Ninian presented himself he was regarding Lucilla indulgently, and drawing her out in a paternal way to talk to him. His sister was not surprised, for being himself a great stickler he was always predisposed to favour girls whose manners showed them to be well-taught and well-bred. He was at first a trifle stiff with Ninian, but Ninian’s manners were very good too, so that by the time they rose from the dinner-table Sir Geoffrey had forgiven him for such signs of incipient dandyism as his uncomfortably high shirt-points, and his not entirely felicitous attempt to arrange his neckcloth in the style known as the Waterfall, and had decided that there was no harm in the boy: no doubt he would outgrow his desire to ape the dandy-set; and the deference he showed to his elders showed that he too had been strictly reared. Sir Geoffrey noted, with approval, that both he and Lucilla treated Annis with affectionate respect; but when the theatre-party had left the house, Annis saw that he was frowning. After waiting for a few moments, she said: “Well, Geoffrey? Is she the sort of hurly-burly girl you expected?”

He did not answer immediately, and when he did speak it was to say, with a hard look at her from under his lowered brows: “I wish you may not have got yourself into a scrape, Annis!”

“Why, how should I?” she asked, surprised.

“Good God, have you windmills in your head? That child you’ve chosen to befriend is no orphan lifted out of the gutter, but a member of a distinguished family, heiress to what I judge to be, from what she told me, a considerable fortune, and brought up by an aunt who may be as foolish as you say she is but who has lavished every care, attention, and luxury on her! What, I ask you, must be her sentiments upon this occasion? To all intents and purposes you have kidnapped the girl!”

“Oh, gammon, Geoffrey! I did no such thing!”

“Try if you can to persuade the Carletons to believe that!” he said grimly. “They can hardly blame you for having taken her up into your carriage when you found her stranded on the road, but they must blame you—as I do!—for not having restored her to her aunt when you discovered what were the rights of the case! You had not even the excuse of believing that she had been ill-treated!”

She was shaken, but made a push to defend herself. “Oh, no, but when she told me of the sort of pressure Mrs Amber was bringing to bear on her—and not only Mrs Amber but the Iverleys too!—I realized, which I daresay you don’t, that she felt herself to be caught in a trap, and I pitied her from the bottom of my heart! If Ninian had had enough resolution to have told his father that he had no wish to marry Lucilla the case might have been different, but it seems that no member of Iverley’s family dares thwart him, because they are all of them afraid that if he flies into a passion he will suffer a heart-attack, and very likely die of it. A contemptible form of tyranny, isn’t it? But I fancy Ninian has begun to recognize it as such, for when he returned to Chartley, having left Lucilla in my charge, he found the whole house in an uproar, not one of his loving family, as it appears, having made the smallest attempt either to conceal the fact of Lucilla’s flight from Lord Iverley, or to point out to him that since Ninian was with her it was extremely unlikely that she had run into any kind of danger. I collect that he had put himself into a rare passion, but so far from its having prostrated him he was in high force, and rattled Ninian off in fine style, without doing himself the least harm. So Ninian lost his temper, packed up his gear, and came back to Bath—to protect Lucilla from the machinations of ‘a complete stranger’! And I can’t say I blame him! Poor boy! He had had the very deuce of a time with Lucilla, and to find himself the target for recriminations and abuse was rather too much for him. He had done his best to persuade her to go back with him to Chartley, but, short of taking her back by main force, there was no way of doing it. And I don’t think he could have done that, for she would certainly have fought him tooth and nail, and nothing, you know, could revolt him more than the sort of public scene that would have created!”

“But this becomes even worse than I had supposed!” exclaimed Sir Geoffrey, deeply shocked. “Not content with having embroiled yourself with the Carletons you have created a breach between young Elmore and his parents! It was wrong of you, Annis, very wrong! I might have guessed you would do something freakish if I permitted you to leave home! Elmore, too! I had not thought it possible that such a well-mannered lad could be guilty of the impropriety of quarrelling with his father!”

“My dear Geoffrey, you’re quite out!” she replied, rather amused. “I haven’t embroiled myself with anyone, and I had nothing to do with Ninian’s quarrel with Lord Iverley. Indeed, I carefully refrained from advising him not to be quite so docile a son, though I was strongly inclined to do so! To own the truth, I was astonished when I discovered that the worm had turned at last, for although he is in many respects an excellent young man I did think him lacking in pluck. I shouldn’t wonder at it if this episode makes Iverley hold him in respect as well as affection. The best of it is that having accused Ninian of having ‘abandoned’ Lucilla to a complete stranger he can’t now rake him down for having come back to protect her. As for Mrs Amber, I wrote her a polite letter, explaining the circumstances of my meeting with Lucilla, and begging her to grant the child leave to stay with me for a few weeks. According to Ninian, she was enjoying a prolonged fit of spasms and hysterics, but although she has not yet done me the honour of replying to my letter she has signified consent by sending Lucilla’s trunks to Bath.”

He could not be satisfied, but continued to enumerate and to discuss all the evil consequences which might result from what he termed her rash action until, in desperation, she induced him to talk instead about his children, with particular reference to little Tom’s tendency to croup, and what were the best methods of dealing with it. Since he was a fond father, it was not difficult to divert his mind from matters of less importance to him, and he was still talking about his children when Lucilla and Miss Farlow came in. Lucilla was in raptures over the play she had seen. She thanked Annis over and over again for having given her such a splendid treat, and disclosed that it was the very first time she had visited a grown-up theatre. “For I don’t count the time Papa took me to Astley’s, because I was only six years old, and I can only just remember it. But this I shall never forget! Oh, and Mr Beckenham was there, and he came up to our box, and made the box-attendant bring us tea and lemonade in the interval, which I thought so very kind of him! What an excessively agreeable man he is, isn’t he?”

“Excessively,” said Miss Wychwood rather dryly. “Where, by the way, is Ninian?”

“Oh, when he had handed us into the carriage he said he would walk back to the Pelican! I fancy he had a headache, for he became stupidly mumpish, and didn’t seem to be enjoying the play nearly as much as I did. But perhaps he was affected by the heat in the theatre,” she added charitably.

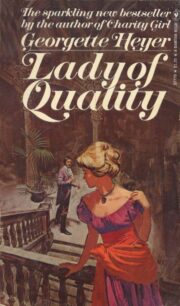

"Lady of Quality" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Quality". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Quality" друзьям в соцсетях.