She clung to Nick for a moment on the landing and stood watching him walk down the stairs, then slowly she turned back. “You really want coffee?”

“Please.” Sam had collected the plates. He carried them through to the kitchen, then he leaned against the wall, watching as Jo set about making some instant coffee. “Not the real thing?” he inquired lazily. There was a slight smile at the corners of his mouth.

“It takes too long,” Jo said over her shoulder. “I mean it, Sam. I really am too tired to talk.” She turned suddenly and looked at him. “Sam-”

He raised an eyebrow.

“Is Nick-” She hesitated. “Have you ever hypnotized Nick?”

Sam smiled. “That’s an odd thing to ask.”

“Have you?”

“Put down the kettle for a moment and look at me.”

“I’m making your coffee.”

“Put it down, Jo.”

She did so, slowly. Then she stared up at him. “Sam-”

“That’s right, Jo. Close your eyes for a moment. Relax. You can’t fight it. There is nothing you can do, is there? You are already asleep and traveling back into the past. That’s it.” Sam stood for a moment staring at her, then he moved forward and took her hand, leading her out into the apartment’s short hall. A right turn would take him toward the front of the apartment, the living room with its open balcony doors. To the left was the bedroom and next to it the bathroom.

He turned left. In the bedroom he pushed Jo into a seated position on the end of her bed, then he moved to the windows and closed the heavy curtains. He switched on the lamp. It cast strange synthetic shadows in a room where the evening sunlight was still struggling through between the folds of the heavy material, lighting up a dazzling wedge of gold on the dusty rose of the carpet.

Sam folded his arms. “So, my lady, do you know who I am?”

Jo shook her head dully.

“I am your husband, madam!”

“William?” She moved her head slightly as though trying to avoid some dazzling light.

“William.” He had not moved. “And you and I have a whole night, do we not, to remind you of your duties to your husband.”

Jo stared up at him, her gaze alarmingly direct. “My duties? Of what duties do you intend to remind me, my lord?” Her tone was scornful.

Sam smiled. “All in good time. But first I want to ask you a question. Wait. There is something I must fetch. Wait here until I return.”

Matilda stared at William’s retreating back. He slammed the heavy oak door of the bedchamber and she heard the ring of his spurs on the stone as his footsteps retreated. She shivered. The narrow windows of the chamber faced north and the shutters braced across them did nothing to keep out the cold. She went to stand near the huge hearth, drawing her fur mantle around her. Her bones had begun to ache now in the winter and she could feel her soul crying out for the balm of spring sunshine. She must be beginning to feel old! What had William gone to find? Wearily she bent and picked a dry mossy apple bough from the basket and threw it on the fire. It scented the room immediately and she closed her eyes, trying to imagine herself warm.

William returned almost at once. He flung back the door and stood before her, his face closed, his eyes hiding some new anger. She sighed, and forced herself to smile.

“What is it you wish to ask me, William? Let us speak of it quickly, then we can go down to the great hall where it is so much warmer.”

What was it he held behind his back? She stared at him curiously, feeling as she always did now for him a strange mixture of scorn and fear and tolerance and even perhaps a little affection. But he was so hard to like, this man to whom she had been married now for so many years.

William slowly held out the hand he had been keeping behind his back. In it was a carved ivory crucifix. She drew back, catching her breath, recognizing it as coming from a niche in the chapel, where it was kept in a jeweled reliquary. It was reputed to have been carved from the bone of some long-dead Celtic saint.

“Take it.”

“Why?” She clutched her cloak more tightly around her.

“Take it in your hand.”

Reluctantly she reached out and took the crucifix. It was unnaturally cold.

“Now,” he breathed. “Now I want you to swear an oath.”

She paled. “What oath?”

“An oath, madam, of the most sacred kind. I want you to swear on that crucifix in your hand that William, the eldest child of your body, is my son.”

She stared at him. “Of course he is your son.”

“Can you swear it?”

She stared down at the intricately carved ivory in her hand-the decorated cross, the tortured, twisted figure of the man hanging on it in his death agony. Slowly she raised it to her lips and kissed it.

“I swear it,” she whispered.

William drew a deep breath. “So,” he said. “You told the truth. He was not de Clare’s bastard.”

Her eyes flew to his face and he saw the paleness of her skin flood with color. For a moment only, then it was gone and she was as white as the crucifix she had pressed to her lips.

He narrowed his eyes. “You swore!”

“William is your son. I swear, before God and the Holy Virgin.”

“And the others? What of the others?” He took a step toward her and grabbed her wrist. He held the crucifix up before her eyes. “Swear. Swear for the others!”

“Giles and Reginald, they are yours. Can you not see it in their coloring and their demeanor? They are both their father’s sons.”

“And the girls?” His voice was frozen.

“Margaret is yours. And Isobel.” She looked down suddenly, unable to hold his gaze.

“But not Tilda?” His voice was barely audible. “My little Matilda is de Clare’s child?” He pressed her fingers around the crucifix until the carving bit into her flesh. “ Is she? ” he screamed suddenly.

Desperately she tried to push him away. “Yes!” she cried. “Yes, she was Richard’s child, God forgive me!”

Abruptly William let her go. She reeled back, and the crucifix fell between them in the dried herbs on the floor. They both stared at it in horror.

William laughed. It was a humorless, vicious sound. “So, the great alliance with Rhys is built on counterfeit goods! The descendants of Gruffydd ap Rhys will not be descendants of mine!”

“You must not tell him!” Matilda sprang forward and caught his arm. “For sweet Jesus’ sake, William, you must not tell him!” She gave a little sob. Dropping his arm, she whirled around, scrabbling on the floor until she found the crucifix. She grabbed it and thrust it at him. “Promise me. Promise me you won’t tell him! He would kill her!”

William smiled. “He would indeed-the fruit of your whoring with de Clare.”

She was trembling. The fur cloak had fallen open. “Please, promise me you won’t tell Lord Rhys, William! Promise!”

“At the moment it would be madness to tell him,” William said thoughtfully, “and I shall keep silent for all our sakes. For now it shall remain a secret between me and my wife.” He smiled coldly. “As for the future, we shall see.”

He stretched out and took the crucifix out of her hand. After kissing it, he put it reverently on the table, then he turned back to her and lifted the fur from her shoulders. “It is so seldom we are alone, my lady. I think it would be a good time, don’t you, to show me some of this passion you so readily give to others.” He carefully removed her blue surcoat and threw it after the cloak before he turned her numb body around and set about unlacing her gown.

She was shivering violently. “Please, William! Not now. It is so cold.”

“We shall warm each other soon enough.” He turned and shouted over his shoulder. “ Emrys! You remember Emrys,” he said softly. “My blind musician?”

She did not turn. Clutching her gown to her breasts, she heard the door open behind her then close again quietly. After a few moments’ silence the first breathy notes of the flute began to drift into the chamber, spiraling up into the dark, smoke-filled rafters.

She shuddered as William’s cold hands pulled the gown out of her clutches and stripped it down to the floor.

“So,” he whispered. “You stand, naked in body and naked in soul.” He took a deep, shaky breath. “Let down your hair.”

For some reason she could not disobey him. Unsteadily she raised her hands to her veil and pulled out the pins that held it. She uncoiled her braids, still long and richly auburn with only a few strands yet of silver, and began to unplait them slowly, conscious of the draft that swept under the door and toward the hearth, sending icy shivers over her skin. She still had not looked at the musician.

William watched in silence until her hair was free. It swung around her shoulders and over her pale breasts, rippled in the firelight into dancing bronzed life.

He took another deep breath and groped at last for the brooch that held his own mantle. “You have a girl’s body still, for all the children you have carried,” he said softly. ‘Trueborn or bastard, they haven’t marked you.” He put his hand on her belly.

She shrank back, her eyes silently spelling out her sudden hatred, and he laughed. “Oh, yes, you detest me-but you have to obey me, sweetheart! I am your husband.” He dropped his cotte after his mantle. “You have to obey me, Matilda, because I have the key to your mind.”

She swallowed. “You have gone mad, my lord!” As if breaking free of some spell, she found she could move suddenly. Turning, she picked up her fur cloak and swung it around her until she was covered in rich chestnut fur from chin to toe. “You hold no keys to my mind!”

“But I do.” Abruptly the music stopped. William raised his hand in front of her face. “Drop the cloak, Matilda. That’s right.” He smiled as, unnerved, she found herself obeying him. “Now, kneel.”

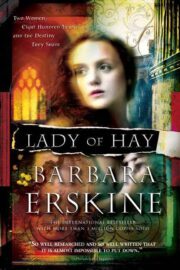

"Lady of Hay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Hay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Hay" друзьям в соцсетях.