She closed her eyes, trying to will some kind of warmth into the cold hardness beneath her hands. The church was completely silent. Tim did not move, watching the woman who, in her cool green linen dress, was as unmoving as the recumbent figure beside her, her tanned skin taking on the tones from the shadows of the nave. He found he was shivering and he fingered the top buttons of his shirt, drawing them together almost defensively.

Jo’s eyes were still closed. He stared at the dark lashes lying on her cheeks and fought the sudden urge to touch her shoulder.

“Oh, Christ! Why won’t it happen!” Jo cried suddenly. She slammed her fists down on the effigy. “I’ve got to know, Tim. I’ve got to. If it won’t happen here, where will it?” She stared around the church. “I’ll have to go back to Carl Bennet. I thought I could manage without him-I wanted to do it alone-”

“Perhaps that’s it, Jo,” Tim said quietly. “Perhaps you need to be alone. Perhaps its because I’m here.”

“Perhaps it is.” She swung to face him. “Perhaps it’s because I want to cash in on it. I wanted to follow Bet’s advice and do the articles for her. When she mentioned a book and even TV the idea excited me. I wanted to use all this, Tim. And it has spoiled it. It has made it contrived. Like you and your camera. You have no place here, Tim!”

“I have, Jo.” He turned away from her and sat down in one of the pews, staring up toward the dark triple-arched chancel, with his back to her. “I do have a place here.”

“I don’t believe you.” She glared at him. “I should never have asked you to come!” She scrambled to her feet and ran toward the door, pulling it open and disappearing out into the sunshine.

Behind her, Tim sat unmoving, listening to the echoing silence as the sound of the falling latch died beneath the church’s vaulted roof.

Jo walked swiftly across the grass, swinging her bag, seeing it scattering the seedheads of the dandelions as she headed toward the overgrown untended half of the churchyard that sloped down steeply around the north side of the church. Somewhere nearby she could hear the gurgling of a brook. It was very hot indeed. The morning haze had cleared away and the full heat of the sun beat down on the top of her head.

She could feel the sudden perspiration on her back and between her breasts as she stopped and looked around. The churchyard was deserted. There was no sign of Tim. With a sigh she pushed her way through knee-high wild grasses, threaded with meadowsweet and campion and buttercups, and sat down on one of the ancient lichen-covered tombs, beneath a yew tree, dropping her bag on the grass. She opened the top buttons of her shirtwaist and turned back the collar, lifting the hair off her neck as she stared up through the thick green of the tree toward the metallic blue of the sky. It was here, or somewhere very close to this spot, that Jeanne was buried. She could hear the drowsy cooing of a woodpigeon in a tree nearby.

Closing her eyes, she leaned back, letting the dappled sunlight play across her face.

The hall of the castle was crowded, wisped with smoke from the fires as the diners sat at the long tables. It was the autumn of 1187.

Matilda was seated at the high table, next to her husband, and on her right was Gerald, Archdeacon of Brecknock. Beyond William was Baldwin, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Gerald leaned toward her with a cheerful grin. “His Grace looks tired. He did not expect his preaching of the Third Crusade in Hay to be greeted by a riot!”

Matilda smiled. “The men of Hay so eager to follow the cross, their wives so eager to stop them! It was ever so, I fear.” She broke off, biting her lip. William had been conspicuous among the men of the Border March in not volunteering to go to rescue the Holy City from Saladin.

Gerald noticed her silence at once and guessed the reason for it. “The king has need of Sir William at home, my lady,” he said gently. “Your husband will give money to the cause, which is as welcome as his sword.”

“Even Lord Rhys and Einion of Elfael pledged their swords!” Matilda retorted. “And William dares to call them savages-” She broke off, glancing at William to see if he had heard, and hastily changed the subject. “Tell me about yourself, Archdeacon. Are you content? You seem to be high in the archbishop’s favor.”

His piercing eyes had lost none of their alertness and never ceased probing the men around him, but now they confronted her quietly as he wiped his lips on his napkin and reached for his wine. “I am never content, Lady Matilda. You should know that by now. I serve the king and I serve the archbishop, but I will confess to you a certain restlessness, a lack of fulfillment.” He put down his goblet so abruptly it slopped on the linen cloth. “God needs me as bishop of St. David’s!” he said vehemently. “Wales needs me there. And yet, still I wait!” He took a deep breath, steadying himself with an effort. “But I have continued with my work. And always I write. That has brought me much solace.” He glanced past her at the archbishop. “Tomorrow we go on to my house at Llanddeu. The archbishop has graciously consented to spend the night there before going on to Brecknock and I have decided to present him with my work on the topography of Ireland. Did you know I was there with Prince John three years ago?” He shook his head wearily. “A fiasco that expedition turned out and no mistake, but it showed me Ireland again. And my book has been well received.”

“You sound as though you dislike the king’s youngest son,” Matilda said cautiously, lowering her voice again.

Gerald shrugged. “One does not like or dislike. He offered me two bishoprics there. But I want St. David’s, so I declined them.” He smiled ruefully. “He is young yet, but he is spoiled. I think he is intelligent and shrewd, but he showed himself no campaigner in Ireland. Perhaps Normandy will teach him something.”

He turned and waved a page forward, holding out his cup to be refilled with wine. “But now, with two of his elder brothers dead, John becomes a man of importance. He is nearer the throne now than he might ever have hoped. His father is old, Geoffrey’s son is a child.” He shook his head mournfully. “And Prince Richard is not yet married, in spite of all. John may yet come to be a force to be reckoned with.”

Matilda shivered. “I don’t trust him.”

Gerald smiled at her shrewdly. “Nor I, my dear. We shall just have to hope that maturity will bring better counsel.” He folded his napkin and placed it on the table. “Now let us speak of pleasanter things. Tell me how your family are. What is the news here?”

Matilda frowned, troubled again. “There I need your advice. You spoke with the Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd yesterday. Is he a good man, do you think?”

Gerald frowned. “A strange question. As you said, he vowed to take up the cross.” He smiled at her. “And his son-in-law, Einion, too. I remember you feared him once, for your children’s sake.” He put his hand on hers as it lay on the table. “But it’s not just that, I can see. What troubles you, my lady?”

“He and William have been discussing an alliance.” She looked down at the white cloth, her mouth set in a hard line. “He wants my little Matilda as wife for his son Gruffydd. William has told me that whatever he thinks of the Welsh he will agree. It is the king’s wish.”

Gerald shrugged. “Gruffydd,” he mused, “is named his father’s heir. He’s not as handsome as his brother Cwnwrig, but he’s tall and strong and he’s able to cope with the quarrels with his brothers. They fight endlessly, you know, the sons of Rhys. They turn the poor man white-haired with worry. He’d probably make the child a good husband.”

“I’m afraid for her, Gerald. I have kept my children safe from Einion and from the rest of Seisyll’s kinsmen and now I’m to be asked to give her to Rhys with my own hands.” She turned to him, suddenly passionate. “Swear to me, Archdeacon. Will she be safe?”

Gerald raised his hand placatingly. “How can I swear? I know Rhys to be a man of excellent wit. He’s honest, discreet, I believe him to be sincere in his quest for peace. More than that I can’t say, although he is my cousin. He wants this marriage obviously to seal this uneasy peace we have on the borders, to make sure the galanas never reappears between your houses. I suspect the power of de Braose is the nearest challenge to his, so he is anxious to secure a peace with you. What better way than by marriage? But all you can have is his promise. It is more than many mothers get.”

He glanced down the hall to where ten-year-old Matilda ate at one of the lower tables with her nurse. Her two eldest brothers, William and Giles, were pages now in neighboring households, as was the custom, while Reginald, her third brother, hovered at a high table proudly serving the archbishop. Matilda’s two youngest children, Isobel and Margaret, were in the nursery lodgings in the west tower. They were a happy, healthy brood of children, some of whom Gerald himself had baptized. He glanced fondly at their mother. She was a young woman, still no more than twenty-six or seven, he guessed, as erect and slim as ever in spite of all the children. He watched her for a moment as she too gazed down the hall at Matilda. It was a miracle that she had not as yet had to bear the grief of the death of a child. He sent up a brief prayer that she would never be broken by such a loss.

Matilda’s gaze went down through the smoky torch-lit hall to fix on her daughter’s face and, as if feeling her mother’s scrutiny, little Tilly raised her eyes. They were clear, almost colorless gray. For a long moment mother and daughter looked at one another. Then Tilly turned away.

Matilda felt her heart tighten beneath her ribs. Always that indifference, that unspoken rejection.

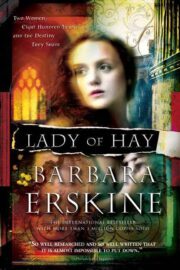

"Lady of Hay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Hay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Hay" друзьям в соцсетях.