“William, William…” Her voice rose to a scream as Will put his arm around her and pulled her away. “William, help us, please! Please, Please help us .”

But already his horse was trotting toward the portcullis as it slid upward into the darkness of the gateway. Seconds later the two figures had vanished into the night.

Matilda collapsed onto Will’s shoulder as Margaret and Mattie ran, consoling, to her side, and slowly they led her back to the tower as the first drops of rain began to fall on the cobbles.

Sam was standing looking out of the window across the square. There were tears on his cheeks as his hand clenched in the curtains. Slowly he turned. “So William left you, my lady,” he whispered, “to fetch the money.” He laughed bitterly. “Did you believe him? Did you wish that you had been a faithful and loving wife? Tell me how it happened, my lady. Tell me how it felt when finally you realized that William was never coming back.”

Jo’s fingers moved restlessly over the cushions on the chair, scratching harshly at the tapestry work, shredding the wool beneath her nails. Her eyes moved unseeing over the flickering TV screen.

“William,” she cried again. “William, for the love of the Holy Virgin, please, come back.”

Tim knocked on the door, easing the heavy camera bag on his shoulder. He was panting heavily after climbing the long flight of stairs.

Judy opened it at the third knock. She was wearing her painting smock and old jeans. She looked slightly harassed as she saw him standing there.

He grinned. “I hope I’m not too late. You did say any time after eight would be okay.”

“Oh, God, Tim, I’m sorry, I forgot. Come in, please.” She dragged the door wider. “I never meant you to go to so much trouble. When I asked you to do the catalogue, I didn’t realize you were going abroad.”

“It’s no trouble, Judy. You put quite a challenge to me. A catalogue of your inner thoughts, not just reproductions of your paintings. How could any photographer resist the temptation to photograph a lady’s inner thoughts!”

She laughed. “I shall obviously have to censor them heavily.” She closed the door behind him. “Can I get you a beer or something?”

Tim shook his head. “I think I’d rather get on. I want to look at the work that’s going to the gallery in Paris and the studio, and I want to look at you.” He smiled at her impishly. “You realize a lot of this will rely on the processing and I’m going to have to leave that to George, but he’ll do it well. I think you’ll be pleased with what he produces.” He put down the bag and pulled it open. “First I want a picture of you in front of that sunset before it fades.”

The back window of the studio was ablaze with crimson and orange. Judy glanced at it. “I’ll change-”

“No! Like that. Jeans, paint stains, everything.” He caught her shoulders and propelled her toward the window, turning her in profile to the light. “That’s it. You’ll be almost totally in silhouette. Just the slightest aura of color around your face and those streaks of red on your shirt. They look like overspill from the clouds.”

He photographed her dozens of times against the window as the light faded to gold and then to green, then at last he turned his attention to the pictures. One by one she brought them forward into the strong studio lights.

“Are you really leaving tomorrow?” She studied his thin, tired face as he raised the light meter in front of a huge, unframed canvas.

He nodded. “Tomorrow evening.”

“And you’ll be gone months?”

“At least three.” He squinted through the viewfinder and then retreated several paces before clicking the shutter.

“Are you going to see Jo before you go?”

He was suddenly very still. “I don’t know. Probably not.” He stepped away from the camera and helped her replace the canvas against the wall. “I had thought I might call in on my way back from here, but I’m not sure. Perhaps it would be better if I didn’t see her again.”

Judy raised an eyebrow. “You made that sound very final.”

Tim gave a harsh laugh. “Did I?” He helped her lift the next picture onto the easel. “Jo has plenty to occupy her without me intruding. I want you in this one, standing facing the painting, that’s it, back to the camera with your shadow cutting across that line of color.”

“It’s only a catalogue, Tim. You’re turning it into a work of art-”

“If you’d wanted anything less you’d have asked your boyfriend to bring his Brownie,” he retorted.

Judy colored. “My boyfriend?”

“Is Pete Leveson not the latest contender for the title?”

Judy stuck her hands in the seat pockets of her jeans. “I don’t know.” She sounded suddenly lost. “I like him a lot.”

“Enough anyway to dish the dirt on your ex-lovers into his lap.”

“Why not?” she flared suddenly. “Nick hasn’t been exactly nice to me. I hope he rots in hell!”

Tim laughed wryly. “I think he’s been doing that, Judy,” he said.

The king rode out of Bristol three days later, leaving his prisoners behind in the custody of the royal constable. They were allowed the use of several rooms in the tower and their babies and the nurses were lodged on the floor above them, but nothing hid the fact that there were guards at the doors of the lower rooms and two men on duty always at the door out into the ward.

Matilda spent long hours at the window of their sleeping chamber gazing out across the marshes toward the Severn and the mountains of Wales beyond. Slowly the last leaves dropped from the woods, whipped off the leaden branches by cutting, easterly winds that blew gusts of bitter smoke back down the chimney into the rooms, filling them with choking wood ash. In spite of the fires they were cold, and though clothes and blankets were brought for them, Matilda seldom stopped shivering. She could not bear to allow the northern window shuttered, watching through the short hours of daylight for the sight of her husband’s horse.

But he did not come.

The feast of St. Agnes passed and no word came, from William or the king. Then as the first snowdrops were pushing their way up through the iron-hard ground a detachment of men arrived escorting two of the king’s household. They were lawyers.

Matilda stood before them alone, wrapped in a mantle of beaver fur, watching their gray, bookish faces for any sign of human feeling or concern.

One, Edward, held out her signed agreement. “Your husband, Lady de Braose, has failed to produce the said sum of money by the agreed date. Are you able to produce the money in his stead?” He looked up at her, mildly curious, uninterested.

Matilda swallowed. “I have money hidden. It may be enough, I don’t know. I’m sure my husband is on his way. Can you not give him a little longer? I’m sure the king-”

“The king, my lady, has had word that your husband is fled to France.” It was the other man speaking. He was seated at the side of the table, idly paring his nails with a knife. “There is no mistake, I’m afraid.” He too was watching her now.

Matilda bit her lip. Now that it had happened she felt calm, almost relieved that the waiting was over.

“Then I must raise the money myself. I hid it with the help of my steward at Hay. There was some gold, jewelry, and coin. We put it in coffers and carried it up to the mountains.”

“This money.” Edward was tracing the writing of the document. “Would it amount to fifty thousand marks?”

“As your husband has defaulted we would require the full amount at once, you see.” The younger didn’t bother to look up this time. He was still working on his thumbnail.

“I was thinking in terms of the first installment,” Matilda groped for her words cautiously. “There would be ten at least, I should think. I could raise more if I were allowed to go to Wales to-”

“Out of the question, I’m sorry.” Edward drew a parchment toward him on the desk. “Did you make no note of the value of the money you hid, Lady de Braose? Perhaps your steward could be found to bring it. If I may have his name we can send riders.”

“There were about four thousand marks in coin, if you must know.” She shrugged. “Most of my jewelry was there. That must be worth a lot, and my husband’s rings and chains, and gold.” She glanced from one to the other, but both men were shaking their heads.

“I’m sorry. It’s not enough.” Edward rose, licking his lips nervously. “I must tell you, my lady, that His Grace has ordered that the judgment of the realm be carried out against your husband. He is now an outlaw in this land. The king has also decreed that unless you were able to meet to the last penny the amount required within three days of St. Agnes’ feast, the day stipulated in the agreement you yourself signed of your own free will, you should suffer the full penalties for your husband’s default.”

He paused as the other lawyer too rose to his feet and began to push the pile of parchments together into a heap. The gesture was somehow very final.

“What penalties?” Matilda heard her voice as a whisper in the silence of the room.

He shrugged. “I have letters for the constable. You and your son, William, are to be removed to the royal castle of Corfe. The other ladies and your grandchildren will remain here for the time being, I gather.”

Matilda looked from one to the other. She could feel her panic rising. “When must we go?”

“Today. As soon as an escort has been mounted.” The two men bowed together and made their way past her to the door. Then they had gone and for a moment she was alone, before the knight who had brought her from the tower was again at her side. “You’d best go and make your farewells, lady,” he murmured kindly. “The constable had an inkling of what the letters were going to say. The men are already summoned to escort you.”

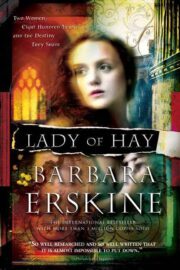

"Lady of Hay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Hay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Hay" друзьям в соцсетях.