“My love?”

“As much as I look forward to sharing a studio with you and arguing with you about the proper use of the color green, I suspect we’re going to have a very large family.”

Elijah’s smile was devilish and sweet. “I suspect we will too.”

They shared several wonderful studios thereafter—at Flint Hall, at Morelands, at their London residence, and in the homes of each of Jenny’s siblings, Elijah having developed a preference for juvenile portraits and subjects being available in quantity.

They also argued over the proper use of every color in the rainbow, and over many other things besides.

And they had a very large, happy family, the first child—Rembrandt Joshua Harrison—making his appearance exactly nine months after the wedding.

Read on for an excerpt from Grace Burrowes’s

bestselling Scottish Victorian series

The MacGregor’s Lady

Available February 2014

from Sourcebooks Casablanca

Hannah had been desperate to write to Gran, but three attempts at correspondence lay crumpled in the bottom of the waste bin, rather like Hannah’s spirits.

The first letter had degenerated into a description of their host the Earl of Balfour. Or Asher, Mr. Lord Balfour. Or whatever. Aunt had waited until after Hannah had met the fellow to pass along a whole taxonomy of ways to refer to a titled gentleman, depending on social standing and the situation.

The Englishmen favored by Step-papa were blond, skinny, pale, blue-eyed and possessed of narrow chests. They spoke in haughty accents, and weren’t the least concerned about surrendering rights to their monarch, be it a king who had lost his reason or a queen rumored to be more comfortable with German than English.

Balfour was neither blond, nor skinny, nor narrow-chested. He was quite tall, and as muscular and rangy as any backwoodsman. He did not declaim his pronouncements, but rather, his speech had a growl to it, as if he were part bear.

The second draft had made a valiant attempt to compare Boston’s docks with those of Edinburgh, but had then doubled back to observe that Hannah had never seen such a dramatic countenance done in such a dark palette as she had beheld on Balfour. She’d put the pen down before prosing on about his nose. No Englishman ever sported such a noble feature, or at least not the Englishmen whom Step-papa forever paraded through the parlor.

The third draft had nearly admitted that she’d wanted to hate everything about this journey, and yet, in his hospitality, and in his failure to measure down to Hannah’s expectations, Balfour and his household hinted that instead of banishment, a sojourn in Britain might have a bit of sanctuary about it too.

Rather than admit that in writing—even to Gran—that draft had followed its predecessors into the waste bin. What Hannah could convey was that Aunt had not fared well on the crossing. Confined and bored on the ship, Enid had been prone to frequent megrims and bellyaches and to absorbing her every waking hour with supervision of the care of her wardrobe.

Leaving Hannah no time to see to her own—not that she’d be trying to impress anybody with her wardrobe, her fashion sense, or her eligibility for the state of holy matrimony.

Her mission was, in fact, the very opposite.

Hannah sanded and sealed a short note mostly confirming their safe arrival, the earl having graciously given her the run of his library.

But how to post it?

Were she in Boston, she’d know such a simple thing as how to post a letter, where to fetch more tincture of opium for her aunt, what money was needful for which purchases.

“Excuse me.” The earl paused in the open doorway, then walked into the room. He had a sauntering quality to his gait, as if his hips were loose joints, his spine supple like a cat’s, and his time entirely his own. Even his walk lacked the military bearing of the Englishmen Hannah had met.

Which was both subtly unnerving and… attractive.

“I’m finished with your desk, sir.” My lord was probably the preferred form of address—though perhaps not preferred by him. “I’ve a letter to post to my grandmother, if you’ll tell me how to accomplish such a thing?”

“You have to give me permission to sit.” He did not smile, but something in his eyes suggested he was amused.

“You’re not a child to need an adult’s permission.” Though even as a boy, those green eyes of his would have been arresting.

“I’m a gentleman and you’re a lady, so I do need your permission.” He gestured to a chair on the other side of a desk. “May I?”

“Of course.”

“How are you faring here?”

He crossed an ankle over his knee and sat back, his big body filling the chair with long limbs and excellent tailoring.

“Your household has done a great deal to make us comfortable and welcome, for which you have my thanks.” His maids in particular had Hannah’s gratitude, for much of Aunt’s carping and fretting had landed on their uncomplaining shoulders.

“Is there anything you need?” His gaze no longer reflected amusement. The question was polite, but the man was studying her, and Hannah felt herself bristle at his scrutiny. She’d come here to get away from the looks, the whispers, the gossip.

“I need to post my letter. When do we depart for London?”

He picked up an old-fashioned quill pen, making his big hands look curiously elegant, as if he might render art with them, or music, or delicate surgeries.

“Give me your letter, Miss Hannah. I’ve business interests in Boston and correspond frequently with my offices there. As for London, we’ll give Miss Enid Cooper another week or so to recuperate, and if the weather is promising, strike out for London then.” He paused and the humor was again lurking in his eyes. “If that suits?”

She left off studying his hands, hands which sported neither a wedding ring nor a signet ring. What exactly was he asking?

“I am appreciative of your generosity, but I was not asking you to mail my letter for me. I was asking how one goes about mailing a letter, any letter, bound for Boston.” Hannah did not like revealing her ignorance to Balfour, but if she was to go on with him as she intended, then his role was not to make her dependent upon him for something as simple as mailing letters, but rather, to show her how to manage for herself.

He laughed, a low warm sound that crinkled his eyes and had him uncrossing his leg to sit forward.

“Put up your guns, Boston. I know what it is to be a stranger in a strange land. I’ll walk you to the nearest posting inn and show you how we shuffle our mail around here. If you still want to wait for the HMS Next-to-Sail, you are welcome to, but I can assure you my ships will see your correspondence delivered sooner by a margin of days if not weeks.”

“Your ships?” Plural. Hannah made a surreptitious inspection of the library, seeing hundreds of books, a dozen fragrant beeswax candles in addition to gas lamps, and thick, spotless Turkey carpets.

“When one is in trade with the New World, one should be in control of the means of distribution as well as the products, though you aren’t to mention to a soul that you know I’ve mercantile interests. Shall we find that posting inn?” He rose, something that apparently did not require her permission, and came around the desk to take her hand.

“I can stand without assistance,” she said, getting to her feet. “But thank you, some fresh air would be appreciated.”

They’d had a dusting of snow the night before, though the sun had come out and the eaves were dripping. Just like in Boston, the new snow and the sunshine created a winter brightness more piercing than the summer sun.

“We should tell your aunt we’re leaving the premises.”

This was perhaps another rule, or his idea of what manners required. “She’s resting.” Aunt was sleeping off her latest headache remedy.

His earlship peered down at her—he was even taller up close—but Hannah did not return his gaze lest she see contempt—or worse, pity—in his eyes.

“We’ll leave a note, then. Fetch your cape and bonnet while I write the note.”

How easily he gave orders. Too easily, but Hannah wanted to be out of this quiet, cozy house of stout gray granite, and into the sunshine and fresh air. She met him in the vestibule, her half boots snugly laced, her gloves clutched in her hand.

“Perhaps you’ll want to wear your bonnet,” he said as a footman swung a greatcoat over his shoulders. Hannah counted multiple capes, which made his wide shoulders even more impressive. Though how such a robust fellow tolerated being fussed over was what Gran would call a fair puzzlement.

The bonnet had spontaneously migrated from whatever dark closet it deserved to rot in to the sideboard in the house’s entryway. “Why would I want to be seen in such an ugly thing?”

“I don’t know. Why would you?”

Propriety alone required a bonnet for most occasions, but she wouldn’t concede that, not when the only bonnet she’d packed was a milliner’s abomination. And yet, when they gained the street, she wished she had worn her ugly bonnet, so bright was the sun. Sun meant spring was coming—not a cheering thought.

“A gentleman would not comment on this,” her escort said as he tucked her hand over his arm, “but I notice you limp.”

That arm was not a mere courtesy, as it might have been from Hannah’s beaus in Boston, but rather, a masculine bulwark against losses of balance of the physical kind.

“A blind man could tell I limped from the cadence of my steps. You needn’t apologize.” The only people in Boston solicitous of Hannah’s limp were fellows equally solicitous of her unmarried state and private fortune, but the earl could not know that.

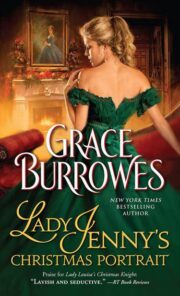

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.