She pointed to the hearth beside Her Grace’s seat in his drawing. “That is a gesture, not a rendering. The light sources in any painting are of a paramount importance, and you’ve barely hinted at the dimensions of the fireplace.”

His hands went to his hips, and he seemed to grow not just taller, but larger. “I know that, Genevieve, but having painted several hundred portraits, I also know that wasting my time in pencil on an object that can be rendered accurately only with paint is dithering.”

She closed the space between them. “And your carping on my perishing, damned shadows is the same!”

That felt good. The consternation in his eyes when she used foul language felt very good indeed, almost as good as kissing him.

“We’re tired,” he said, his gaze on their sketches. “All of this will be here in the morning. We can shout at each other further then. Better still we’ll get out the paints and inspire you to more cursing. Please promise me, however, that you won’t curse in front of your parents.”

As if she could.

She was tired, tired from spending most of the day in this room with Elijah Harrison, being close enough to catch his lavender scent, to see the way he studied his sketch as if composing a sermon for its betterment, to watch how his beautiful lips firmed when he was concentrating most closely on his work.

Jenny was also tired from trying to see her parents not as the people she’d known and loved since birth, but as subjects for portraits.

Mostly, she was tired of exercising the discipline necessary to not touch him.

“I don’t want to shout at you, Elijah.” She wanted to put her arms around him and feel his arms around her. With him in his shirtsleeves and waistcoat, his cuffs turned back to reveal his wrists and forearms, she wanted very much to touch him.

He moved the sketches aside and used the table as a bench, scooting back to sit on it. “The French shout, Genevieve. They are a pugnacious, articulate people, and not without prejudices where women are concerned, for all their talk to the contrary.”

She took the place beside him. “You are telling me Paris will not be a bed of roses. I know that. Are you hungry?”

Clearly, the question surprised him. “I am. It’s late, though. Shall I escort you to your room?”

This was not an offer to accompany her to bed. This was Elijah being proper, and Jenny nearly hated him for it.

“Come with me.” She hopped off the table and grabbed him by the wrist. “Papa is always testy when he’s peckish, and I’m no different.”

She didn’t turn loose of his wrist, but towed him along through the darkened house. The cloved oranges lent the corridors a holiday fragrance, while mistletoe dangled from the rafters.

“Is there a reason you’re not having a late-night tea tray sent up to your room?” Elijah asked.

“The staff is exhausted from the preparations for all the arrivals tomorrow. The larder is full to bursting though, and nobody will miss what we help ourselves to now.”

The kitchen was in a lower corner of the house, where access to water was assured by an ancient well in the cellars, and where the pantries and gardens were close by.

“I have always liked kitchens,” Elijah said as they gained the darkened main kitchen. “They are warm in winter, and they say a lot about a family.”

“I should have pried you loose from that studio earlier.” Jenny dropped his wrist and took a candle into the cook’s pantry. She appropriated butter, bread, an apple, and a wedge of cheese.

“You can slice us some ham,” she said when she emerged with her platter. “I’m going to make chocolate.”

She expected an argument, because for the past three days, they’d mostly argued. Twice she’d caught Elijah regarding her with an expression she could not fathom, but both times, he’d dropped right back into his art.

His damnable, excellent art.

“Who were today’s letters from?” She fetched the pitcher of milk from the window box and stirred up the coals in the hearth.

“My two middle brothers. There’s an epistolary siege underway. Is this enough ham?”

“You could eat twice that amount yourself. What is the objective of the siege?”

The knife came down on the cutting board loud enough to make a “thwack!” in the shadowed kitchen. “My pride is being besieged. I made a vow I would not return to Flint Hall until I’d gained entry into the Royal Academy. My dear siblings”—Thwack!—“would have me violate that oath.”

Jenny snitched a bite of ham. “So would I.”

“Watch your fingers, Genevieve. What do you mean?”

She held up a bite of cheese, wanting him to nibble it from those fingers. He instead took it from her and held it, his posture expectant.

“How old were you when you made your infernal vow?”

He popped the cheese in his mouth and chewed slowly. “I’d gone up to university. I wasn’t a child.”

She moved away, to the hearth, where the pan of milk was beginning to steam over the coals. “The chocolate is in that tin on the counter and the grater is right beside it.”

Elijah had made hot chocolate before, apparently. He ground off an appropriate portion of chocolate and sprinkled it into the heated milk while Jenny stirred briskly. Next came a dash of salt, some spices, and a bit of sugar.

“I’ve never had it with cinnamon before,” Elijah said, setting two mugs on the table near the fire. “Why do you think I should go home this Christmas, Genevieve?”

She followed with the tray, thinking this was a meal designed to nourish more than the belly.

“You know what folly I got up to at an age when most boys go off to university. I wanted to marry Denby.”

He took the tray from her, pausing for a moment so they were both holding it. “You wanted to marry him?” His tone suggested that a desire to contract the plague and pass it along to the regent would have been easier to fathom.

“I was sixteen, Elijah. I was even younger when I sent my brother Bartholomew off to war.”

He gestured with the tray. “Sit and explain yourself before the chocolate gets cold. You did not send your brother off to war.”

She sat at the head of the table, so they would be neither beside each other nor directly across. “I love the scent of cinnamon. Bart liked it in his chocolate too.”

“He would be your late older brother?”

Late—a euphemism for dead, but not much of a euphemism. “One of my late older brothers.”

Elijah slathered butter on a piece of bread, added ham and cheese, and passed it to her. “And you sent him off to war?”

She studied the food, studied her mug, and took a fortifying whiff of cinnamon and nutmeg. Elijah ought to go home; she knew this as clearly as she knew her destiny lay in Paris.

“Adolescents are prone to righteousness. Bart made the mistake of teasing me about my drawing once too often, and I—I suspect my female humors were in part to blame—I came at him with guns blazing.”

“You could not aim a gun at a living creature to save yourself.” He made himself a sandwich twice the thickness of Jenny’s.

“I have a temper.”

He munched a bite of sandwich. “You are passionate where your art is concerned.”

Only her art? Jenny’s hands tightened around her mug, because the idiot man was humoring her. “I appropriated my mother’s tactics. His Grace rants and blusters when he’s in a temper, but his words are not intended as weapons. Her Grace’s artillery is much quieter. She sniffs, she frowns, she mentions, she lets a quiet question hang in the air, and one is devastated.”

Elijah took up a knife and the apple. “What did you mention to your brother?”

Jenny set her mug aside, the scent of spices no longer appealing. “I mentioned that I was ashamed of him. He’d finished his studies and was idling about, getting his younger brothers into trouble, making Mama worry, and starting up horrible rows with His Grace. He drank excessively, at least by my juvenile standards, and he terrorized the maids.”

“If you knew that and you were his lady sister and little more than a child, then he should have been ashamed. Have a bite of apple.”

Elijah held out his hand with four eighths of an apple in his palm. She took two.

“You aren’t going to tell me young men are full of high spirits? That a young man needs to learn to hold his drink? That a ducal heir should have lived long enough to outgrow those high spirits? To produce the next heir?”

Elijah crunched off a bite of apple, the sound healthy and… reassuring. “If he’d finished his education, Genevieve, Lord Bart had had three years in that expensive conservatory of spoiled young manhood known as Oxford. He’d had years to lark about, chase the tavern wenches, learn to hold his liquor, and acquire the knack of living within an allowance. By the end of my first year there, I was serving as banker to the older boys, and had taught one of the chambermaids the rudiments of reading.”

The notion that not all heirs to titles had a misspent youth was novel. “Why?”

He passed her sandwich to her. “Because I am the oldest of twelve. I could not do otherwise. The cost of educating six boys and launching six girls is substantial, even for a man as wealthy as my father. I could not countenance squandering my education or setting an example that would allow any of my brothers to squander theirs. Eat your sandwich.”

She took a bite and chewed, finding both the food and the conversation fortifying. “Bart was not the oldest, not really.”

“He was the heir to a much-respected dukedom, which is responsibility enough. He was also likely at or near his majority by the time you took him to task, and I say it was high time somebody did.”

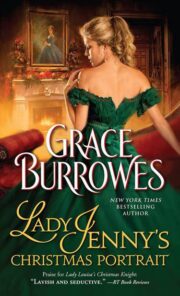

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.