Elijah passed his host an empty glass. “My thanks, Your Grace. Perhaps we could focus first on the painting for Her Grace that you mentioned in your note?”

In his summons, more accurately. The epistle had been three sentences long, and every word had savored of imperatives.

His Grace handed Elijah back a half-full glass, topped up his own drink, and resumed a seat on a blue velvet sofa near the fire. The blue of the velvet brought out the blue of Moreland’s eyes, something Lady Jenny had probably often noted.

“I still managed to look distinguished,” His Grace said. He wasn’t smiling, and the words bore no humorous inflection, and yet Elijah had the sense the man was poking fun at himself. “I’d like to memorialize myself for Her Grace before old age transmogrifies dignity into stubbornness and ducal consequence into pomposity.”

A towering need to search the premises for Genevieve Windham receded—but did not disappear—as Elijah considered his host’s words. A portraitist often became a repository for confidences, a consequence of time spent in close proximity to people who could not camouflage their thoughts and emotions with activity.

“This is not a public portrait, then?” And how did one convey on canvas the essence of a man who could use the word transmogrify convincingly?

His Grace considered his drink. “This is a gift for my duchess, not a statement of Moreland power and influence. The woman I love deserves such a token, but it’s one I’ve neglected over the years. To sit for a portrait has always seemed… arrogant, to me. Her Grace would have it otherwise, and so you see before you a willing subject, as it were.”

To Elijah, His Grace’s casual use of the word “love” was more impressive than all the polysyllabic blather Moreland had at his command. “My recent work at Sidling notwithstanding, I do not make a credible holiday guest under your roof, Your Grace. Her Grace will have to know the portrait is being done.”

“Young man, do you think I’m going to sit still for hours with only your company to occupy me? Of course Her Grace will know. She will supervise the entire undertaking, making sure I behave myself adequately to see the painting completed. You will consult her on every detail of the composition, and thwart her wishes at your mortal peril.”

This was beyond an imperative; this was Moreland Holy Writ, perhaps Windham family Holy Writ as well.

“Of course, Your Grace, though to finish the portrait between now and the first of the year will be difficult. I haven’t yet completed Sindal’s commission, and I’m sure you’ll have holiday duties that interfere with your sittings.”

“You are a bachelor, so allowances must be made.” His Grace rose, took up the poker, and jabbed at the fire. Elijah studied the duke’s movement, the way he hunkered before the hearth, the confidence with which he wielded a substantial length of wrought iron.

His Grace was not merely spry, as that adjective was applied to old men who yet managed to dodder around unaided. The duke was limber, lithe, and strong, full of energy and… determination.

“When you wed,” Moreland said as he replaced the poker in its stand, “you will understand that he who fails to make proper gifts at the proper time where his lady is concerned risks disappointing that lady, and living with the shame of his failure well beyond the end of the occasion. Do you know why I maintain a conservatory here, Bernward?”

“To protect delicate plants over the winter and conserve them for the next year’s spring.”

“To give my duchess flowers when she’s in need of them. You’re here for the same purpose, to give my duchess a portrait when she’s in need of one.”

No, Elijah was at Morelands because he could not get out of his mind that sketch Genevieve had done of him when he’d been trying to write to his sister. The rendering had been accurate, but it had been another image of a lonely man—also a man bewildered by a simple bit of correspondence to a younger sibling.

And in some dim corner of his brain, Elijah perceived that the answer to his loneliness lay in Genevieve Windham’s hands—or at least the temporary relief of it.

“I’ll need some help if I’m to be done before Christmas, Your Grace. Perhaps Lady Jenny might again assist me?” He took the last sip of his drink in hopes that request might come across as casual.

“What says you have to be done before Christmas?”

Lady Jenny’s travel plans said it plainly enough. “The Academy announces its new members along with the honors list, Your Grace. I’d like to be back in London to congratulate the new Academicians.”

And he did not want to be here when Jenny went on her wrongheaded, misguided, unnecessary pilgrimage to Paris. For it was a pilgrimage, though Elijah had yet to determine what transgression on Jenny’s part necessitated such a penance.

“You will not disappoint my duchess, Bernward. The portrait will be done in time for our open house on Christmas Eve.”

“As you wish, Your Grace.”

“Then be off with you. Any footman can see you to your quarters. Jenny’s about somewhere, unless her sisters have impressed her into doting on their offspring again. Ask the footmen. Put off dwelling at the family seat as long as you can, Bernward. One loses track of one’s family in these old mausoleums.”

Bernward. The title didn’t feel as awkward coming from Moreland as it might from many others. “Thank you, Your Grace. Am I to join the family at meals?”

One could wait above stairs in evening attire for a summons that never came, or one could plainly ask.

“For God’s sake, of course you will dine with us. Her Grace would never forgive me if I suffered Charlotte Beauvais Harrison’s darling boy to shiver away his meals in a garret. And you have some correspondence.”

The duke stalked over to the mantel and swiped up no less than three letters, which he shoved at Elijah. “Your womenfolk are after you, and spying on my house, no doubt. Never underestimate the espionage of females, Bernward. You will tell your sisters Morelands is gracious, snug, and majestic—regardless of drafty corridors, tipsy maids, or footmen who linger near the mistletoe.”

The tone was gruff; the wink was charming. Elijah took the letters, feeling as if the Earl of Bernward had just been welcomed into some benevolent protective society of males who must endure the holidays without cursing before the womenfolk.

“My thanks, Your Grace.”

Elijah took his leave, and had spotted no less than eight fat sprigs of mistletoe before he paused to wonder how his family had known he’d be at Morelands, when four days past Elijah himself had been convinced his next destination was Northumbria.

Twelve

“So tell me, my lady, do you like it?”

Jenny looked up to see Elijah Harrison standing in the doorway of her newly christened studio. Had she not been studying his parting gift to her, she would no doubt have sensed his presence.

“You came back.” She could not help but smile as she spoke.

“One does not refuse a ducal commission. It’s said Moreland has influence in every corner of government, and his duchess in every corner of Society. Then, too, as the duke himself informed me, any number of juvenile subjects are expected here over the holidays, and I’m intrigued by that potential.”

These words constituted a credible, if wrong answer. The heat and tenderness in Elijah’s gaze as he prowled across the room gave Jenny far more cause for rejoicing. “You’ve closed the door, Mr. Harrison.”

“Elijah to you, though it seems I’m becoming Bernward to the rest of the world.” He stood very close to her, so close she could catch his sweet lavender scent. “Happy Christmas, my lady. Did you like the sketch?”

He did not kiss her, and the frustration of that was profound.

“I cannot show this sketch to anybody, Mr. Harrison. No one but my lady’s maid has seen my hair down for years.”

His eyebrows spoke volumes: he’d seen her hair down, her body naked, her face suffused with arousal. Thank God he’d sketched her in the grip of other emotions: pensiveness, a hint of humor, and something else she couldn’t name.

“You’ve caught a resemblance between me and His Grace. I can’t say I’ve noticed that before, but the likeness is genuine.”

“You have much of your father in you. Will you lend me your studio?”

He moved off, and Jenny wanted to grab him by the hand and drag him down to the carpet, there to renew his acquaintance with her unbound hair until spring.

“Who is to sit to you? I’m fond of my nieces and nephews. I assume you’ll allow me to assist again?”

He paced to the windows, which looked out over the stables and paddocks, toward Kesmore’s estate and Eve’s little manor at Lavender Corner. “My sitter is more fractious than any juvenile subject. His Grace has taken a notion to present his duchess with a portrait for the Christmas Eve open house. The light here is good.”

“I’m having a parlor stove brought up too. Her Grace will love a portrait of Himself.” Why haven’t you kissed me? Do you carry the lock of hair I gave you?

He turned and propped his backside against the windowsill, a pose Jenny’s brothers often adopted. “We never had a chance to paint together at Sidling, Genevieve. Would you enjoy that?”

Zhenevieve. “Yes. And you will critique my work.” Not better than kissing, but some consolation.

“And you will critique mine. I’ll have my equipment set up here.” He sauntered toward the door, and while that view was agreeable, his departure without even touching her was maddening.

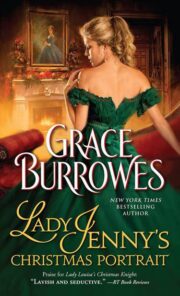

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.