She took his proffered hand and rose. Whatever she might have said was lost to Elijah when somebody tapped on the door.

He dropped her hand and stepped back. “Come in.”

“Greetings, you two.” Vim, Baron Sindal, stood in the door in all his blond, Viking glory. If he thought it odd the room held neither children nor nursemaid, he did not remark it. “I come with a summons from my baroness. Luncheon is served, and then we’re to hitch up the sleigh and invade Louisa and Joseph’s peace for the afternoon.”

Perhaps that was for the best. Perhaps breathing room was a good idea all around. “Lady Genevieve, enjoy your outing. I’ll make a start on a canvas of this morning’s sketch.”

Sindal winged his arm at Jenny. “There’s a letter waiting for you down in the library, Harrison, and your painting will have to wait. Sophie was very clear that you’re to join us on the outing. She was sure you’d enjoy renewing your acquaintance with Kesmore, and I wouldn’t dream of sparing you my sons’ company when they’re in high spirits.”

He sauntered out with Jenny on his arm, a gracious host about his daily quotient of mischief. When the door clicked shut, Elijah lowered himself to the floor beside the old hound.

“I am not a stupid man, I’ll have you know.”

The dog thumped its tail once.

“I understand what Sindal was saying. He was warning me that no footmen were allowed up here to interrupt our morning’s work with anything so distracting as delivery of the post.”

Another thump, and amid the dog’s wrinkles, two sad, sagacious brown eyes opened.

“He was telling me he’s on to us, which probably equates to a warning that he’ll break my fingers if I trifle with his wife’s sister. He did not ask about the portrait. Neither he nor his lady nor old Rothgreb himself have inquired once about the portrait.”

In which, according to Genevieve, Elijah had “caught the love.”

He picked up his sketch. “She adores me. Said almost as much in plain English.”

Saying the words out loud sent warmth cascading through Elijah’s chest. He studied his work more closely, relieved to find that even on a deliberate critical inspection, the sketch still struck him as having that ineffable something that made an image art, and an accurate likeness a portrait.

The boys were the dominant elements of the sketch, and yet, there was Genevieve Windham in all her beauty at the center of it.

Her words came back to him as he noted details he didn’t recall sketching. You’ve caught the love. Like he’d contracted a rare, untreatable condition.

Which… he… had. His first commission of a juvenile portrait was going to be a resounding success because he’d caught the love. Lady Genevieve adored his work, him, and the pleasure they could share, and looking at the image he’d rendered of her, Elijah realized he adored her right back.

Alas for him, she adored Paris more.

“You must tell me how my son goes on.” Lady Flint accepted a second cup of tea from Her Grace, the picture of a gracious caller enjoying her hostess’s company, and yet, Esther saw the shadow in her guest’s eyes.

“I will report faithfully, you may depend upon it, Charlotte, but doesn’t the boy correspond?”

If Esther’s sons failed to write regularly, they knew a visit from their mama might well result—and from their papa. Then, too, the duke was an excellent correspondent—like any competent commanding officer—and set his sons a good example in this regard.

Lady Flint grimaced at her teacup. “Elijah is nothing if not dutiful. He writes to his father at least quarterly, and by some tacit understanding among their men of business, each always knows where the other is, but the letters…”

Esther put a pair of tea cakes on a plate and set them in front of her guest. She’d received Lady Flint in her private parlor, an airy, gilded space done in blue, gold, and cream. Esther kept sketches of her children on the walls, and considered this, rather than any of the formal parlors, her Presence Chamber.

Or perhaps her confessional. “When our boys write, their letters are like dispatches, particularly St. Just’s. They report crops and calves and nothing of any importance. The ladies must keep me informed of what matters—is everybody in good health? Is the baby walking yet? What were the child’s first words? When might a visit be forthcoming?”

“Dispatches—yes. Elijah should hire out as a weather observer. I know the propensity for rainfall in nearly every shire, know when the first frost is likely, and when the lavender blooms. But I do not know…”

Esther pushed the tea cakes closer to her guest. Percival would have polished both off by now. “You do not know how your child fares.” And now came the delicate part. “Does he enjoy travel, your Elijah?”

Charlotte picked up the little plate with the tea cakes on it, and regarded the contents as if they might reveal the future. As a young woman, Charlotte had never wanted for beaus, and it was her hands they all wrote sonnets to. French hands, maybe, graceful even in repose, hands Esther had envied at the time but did not envy now.

“Of all my boys, Elijah was the one least inclined to leave Flint. He loved the place, knew it as only a boy can know his home. He would harangue his father about which field ought to fallow, which ought to be planted in hops, and he was often right.”

Esther took a nibble of a vanilla tea cake with lemon icing—the chocolate ones being reserved for His Grace. “And yet one hears your son hasn’t been home for quite some time.”

This was offered as a puzzled observation, and a mild judgment on the foolishness of young men. In no way did Esther intend her words as an accusation, though she knew they would be perceived as such.

“Elijah is as stubborn as Flint.” Charlotte set the cakes down uneaten. “They had words years ago as only a young man and his father can, and Elijah galloped off in high dudgeon, determined to pursue his art. Flint maintains our son will come home—that Elijah is too dutiful not to—but when, I ask you, will Elijah come home, if in ten years he’s not set foot on the property even once?”

Esther wanted to hug her guest, for this sorrow was something one mother might share only with another, and yet, Charlotte had her pride too.

“Shall I lecture your son, Charlotte? I’ve had some practice at it, and not just with my boys. You will sympathize with me, I know, when I say that dear Percival occasionally benefits from his wife’s gentle admonitions.”

The moment lightened, as Esther had hoped it would.

Charlotte picked up the plate of cakes and took a dainty nibble of an almond and cherry confection. That a woman who’d borne twelve children had any daintiness left in her was a testament to significant fortitude.

“Matters are likely to come to the sticking point here directly,” she said when she’d munched her cake. “Elijah is under consideration as a full member of the Royal Academy. He vowed—young men are so dramatic—he vowed he would not set foot on Flint soil again until he’d gained full membership, and he will not be voted in.”

“Flint would do such a thing to his own son?”

“Flint would dearly love to see Elijah gain Academician status, but it isn’t meant to be. The nominating committee includes old Fotheringale, and he will never allow it.”

The worst problems were those created by a confluence of stubbornness and pride. “Mortimer Fotheringale wouldn’t know a decent portrait if it fell off the wall and hit him on his fundament.”

They shared a look, a look possible only when two ladies had made their bow the same year, and that year was three-and-a-half decades past.

“His arse,” Charlotte rejoined, starting on the second tea cake. “Back in the day, Mortimer fancied me, and I chose Flint. Flint was a dab hand with the caricatures, and I preferred a fellow who could make me laugh to a man who’d lecture me. Mortimer was always going on about the proper helmet for this or that naked Roman god when portrayed at an obscure moment in some unhappy myth.”

“If the Roman were naked, and as a young woman you could focus on his helmet, I would worry for you, Charlotte.”

An impish, Gallic smile flitted over Charlotte’s face, then faded. “Worry for me anyway. Fotheringale is wealthy and respected now, and he will sway many votes. I cannot blame him for wanting a wife of good fortune and good standing—marriage was not a sentimental undertaking thirty-some years ago—but he very much holds it against Flint for turning my head.”

“Have some more cakes. My husband claims tea cakes can solve many ills, and Percival is considered a wise man.” By most, anyway. Hearing this tale of masculine stubbornness and grudges, Esther wasn’t at all sure Percival had been a wise papa where Jenny was concerned.

Charlotte accepted two more cakes, one vanilla with orange frosting, the other vanilla with lavender frosting. “We should serve tea cakes in the Lords.”

“We should lock your son and his father in a room and not let them have any cakes or let them out until they’ve reconciled.”

Thank God her own boys hadn’t gone haring off in a snit—except Bartholomew had to some extent, and the army had been the best thing for him, up to a point.

“You must not interfere, Esther. Flint claims Elijah will find his own way home, but their situation is complicated by Elijah’s art and Flint’s lack of recognition in artistic spheres. I’ve promised my husband I won’t intercede, though I’ve often regretted that promise.”

As well she should. When a man misstepped with his children, who was to set him back on a proper course if not his dear wife?

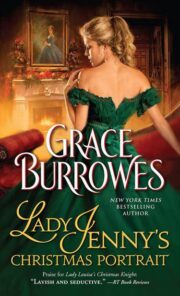

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.