“Sir, may I be of assistance?” She hovered in the door, a blond angel on a miserable winter night, not welcoming him inside and not refusing him entry—a succinct metaphor for Elijah’s dealings with Polite Society.

“I must beg your hospitality, my lady, for my horse has gone lame, and the weather is worsening. Elijah Harrison, at your service. I left the last posting inn some miles back and have seen no other hostelries along the way.”

He shivered in the wind and sleet and tried not to let his teeth chatter. He was ready for her to refuse him or tell him to go ’round back and seek entry of the cook. The very fingers by which he made his living—and a number of other parts—were long since numb, or he would not have knocked on even this door.

The lady stepped back and gestured him inside. “Gracious heavens, Mr. Harrison, come in this instant. I hope the grooms are seeing to your horse?”

Her green eyes were lit with concern, and not—bless her—for his horse.

“My thanks.” He passed into the warmth and quiet of the Earl of Kesmore’s country house as she closed the door behind him. “When last I saw him, the beast was being led into a cozy stall, his limp improving apace at the prospect of straw bedding and a ration of oats.”

“I’m Jenny Windham,” she said, and that she would eschew her title—as he had eschewed his—caught his curiosity. “The servants are quite done in, today being Stirring-Up Sunday. Let me take your coat.”

She hefted the sodden wool from his shoulders and hung it on a hook, spreading the capes and sleeves just so, the better for the garment to dry. This attention to Elijah’s outerwear gave him a moment to study her the way a portrait artist was doomed to study all others of his own species.

Her hands had a competence about them he would not have expected from a duke’s daughter. She dealt with wet fabric as any yeoman’s wife might, then held out a hand for Elijah’s scarf.

“I’ve never seen it rain ice,” she said. “An occasional sleety afternoon, yes, but not this… this”—she grimaced at his scarf—“unending mess. Nobody will be going anywhere if they have any sense. I hope you hadn’t far to go?”

Again the concern in her eyes, and for an uninvited guest who had no business inconveniencing her.

Elijah focused on peeling off damp wool and sopping gloves. “A few more miles yet, but I’m not familiar with the neighborhood, and nothing good ever comes of forcing a lame horse to soldier on.”

“Nothing good at all. You must accept our hospitality tonight, Mr. Harrison. You’ll come with me to the library.”

She did not explain to him that the earl and his countess would be down shortly to welcome him properly, though Elijah well knew this was Joseph Carrington’s house. He would not have presumed to knock otherwise.

And yet he followed Lady Genevieve down a dimly lit corridor without protest, watching the way her carrying candle and the mirrored sconces moved light and shadow across her feminine form. By the time they reached the library, Elijah’s feet were starting the diabolical itching that accompanied a thawing of limbs too long exposed to winter’s wrath.

“You can warm up in here, and we’ll have a room prepared for you,” Lady Genevieve said as she set her candle on a delicately scrolled chestnut sideboard. When his gaze fell upon an embroidery hoop left on the sofa, Elijah realized the lady herself had occupied the library earlier.

“You’re burning wood.” The sweet tang of wood smoke blended with other scents—beeswax, cinnamon, and something floral, an altogether lovely olfactory bouquet.

“Lord Kesmore prefers to burn wood, and his home wood is extensive. If you’ll give up those boots, Mr. Harrison, I’ll have somebody take them down to the kitchen for a polishing. Leave it any later, and the boot boy will have gone to bed.”

Stirring-Up Sunday saw the plum pudding tucked into its brandy bath. The kitchen had no doubt been a merry place for much of the day, and the help would need to sleep off the results of their exertions.

How he loathed Christmas in its every detail.

“I’ll wrestle my boots off, but please don’t put anybody to any trouble. I would not want to impose on his lordship’s staff unnecessarily.”

He did not elaborate, leaving her another opportunity to explain that his lordship wouldn’t find it any imposition, and would be told immediately of his visitor.

“I’ll see to some sustenance for you, Mr. Harrison. Please make yourself comfortable.”

She bobbed a curtsy; he bowed. The moment she left the room, Elijah picked up the embroidery hoop to study the gossamer-fine chemise it held. The itching was climbing from his feet to his calves, and would soon overtake his thighs, but he’d seen such needlework only on his mother’s very own hoop, and the artist in him had long grown used to ignoring all manner of bodily inconveniences and urges.

Jenny returned from the kitchen to find her guest standing before the fire in his stocking feet and shirtsleeves, her embroidery hoop in his hands.

Which would not do. It would not do at all.

“Come eat, Mr. Harrison. I gather the making of the plum pudding occasions something of a celebration among the staff, and so the larder boasted impressive offerings. They’ll be decorating the house tomorrow in anticipation of the Yule season.”

His dark brows lowered and, more importantly, he set her embroidery hoop on the mantel. “I apologize for my state of undress, but my coat was damp.”

Said coat—more sopping than damp—was now draped over the back of a chair set close to the fire, steam rising from the fabric.

Which accounted for the wet-wool scent accompanying the cozier fragrances wafting through the library. Jenny set the tray on the low table before the hearth just as the eight-day clock in the hallway chimed the hour.

“Don’t stand on ceremony, Mr. Harrison. You must be famished.”

And as for his state of undress… Jenny knew firsthand that for all his height, he was lean and hard, every muscle and sinew in evidence when he was naked. Every rib, every pale blue vein, every dark, curling hair on his chest… and elsewhere.

“May I pour for you, sir?”

“Please.”

She took a place on the sofa while he remained standing, which reminded her that whatever else was true about Mr. Elijah Harrison, he had the manners of a gentleman. “You must sit, or you will get crumbs all over the countess’s carpet, and she will not be pleased.”

He came down on the sofa, making the cushions bounce and shift with his weight. “I gather mine host and his countess have already retired?”

A maiden-aunt-in-training ought to expect such questions.

“I would not know. They are from home, and I am keeping my nieces company in their absence. How do you take your tea?”

He was given to silences, which Jenny should have expected from a man who painted for a living. Some artists were so mentally busy trafficking in images that words came to them only reluctantly—a sorry, second-rate form of communication.

“Lady Genevieve, if I know we are without chaperonage, then I will mount my lame horse and find other accommodations. I account Kesmore among my few friends and would not want to give him offense.”

To go with his beautiful body and his beautiful hands, he had a beautiful, masculine voice. She could have listened to that voice recite Scripture and still pictured him without his clothes.

“My aunt is abed on the next floor up.” She paused midreach for the teapot. “You used my title.”

His mouth didn’t shift, but something in his eyes suggested humor. “I make a habit out of attending many of the London social functions. Because I must work in all available daylight hours, I spend most of my evenings dozing in the card room. Even so, I have observed you often from a polite distance.”

Something about the way he used the word observed had Jenny fussing with the tea things. She was rattled by his disclosure, so rattled she fixed her own cup of tea first, with both sugar and cream.

Did he know she’d observed him as well, for hours, when he’d worn nothing but indolence and an offhand sensuality?

“You are prescient,” he said, lifting the full cup. “You know how I like my tea.”

The humor had found its way to his voice, which made Jenny curious to see what a smile would look like on that full, solemn mouth. For all the parts of him she had seen, she had never seen him smile.

“A lucky guess,” she said. “Just as finding your way to Kesmore’s doorstep tonight must have been good luck for you.”

“And for my horse.” He saluted with his teacup, his fingers red with returning circulation.

“Eat something.” Jenny passed him an empty plate. “Chasing the chill from your room will take some time, and you have to be hungry.”

As he filled a plate with as much buttered bread, ham, and cheddar as any one of Jenny’s brothers might have consumed at a sitting, Jenny indulged in closer study of her guest. His dark hair was damp, and around his eyes, fine lines gave him a world-weary air. He was not a boy, hadn’t been a boy for years.

She’d had particular occasion to admire his nose. The nose on Elijah Harrison’s face announced that no compromises would be made easily by its owner, no goal casually cast aside for costing too much effort. Had she not seen the entire rest of him, she would have chosen that nose as his best feature.

He paused between assembling his meal and consuming it. “You’re not eating with me, Lady Genevieve?”

He’d said her name with a little glide on the initial G—“Zhenevieve”—the way a Frenchman might have said it. He had studied in France. Somehow, despite the Corsican’s protracted nonsense, Elijah Harrison had managed to study in France. She envied him this to a point approaching bitterness. “I’ll nibble some cheese.”

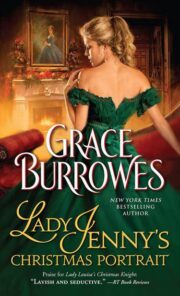

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.