“I’ll show you what a visage is, if you’ll challenge your aunt at Patience.”

At Kit’s age, Patience was an exercise in flipping cards face up, making quite the fuss over any random matches. Nobody won, nobody lost, and nobody tried to keep track of where any cards might lie.

Jenny, however, kept track of Mr. Harrison. He sat against the hearthstone, legs splayed before him. William contentedly straddled one muscular thigh, while the sketch pad was propped on the other. Mr. Harrison’s left hand absently braced William against his body as the right moved the colored chalk across the page.

Both of them, man and boy, looked at ease. William was examining a red pastel, dashing it against Mr. Harrison’s dark wool trousers and leaving jots of red powder. Mr. Harrison was dashing his colors against the page in more fluid motions, though his expression bore the same concentration as William’s.

“Your turn, Aunt Jen.”

Jenny flipped over two cards, the queen of hearts and the queen of spades. “A match. Where shall we put their highnesses?”

“Give them to me!” Kit propped the queens face out against Mr. Harrison’s outstretched leg and soon had a family of royal spectators aligned there.

Mr. Harrison suggested that the twos might also enjoy the view from the gallery and could serve as footmen to the royal family. He offered this casually, an aside murmured between glances at Kit, glances at the page, and glances at Jenny.

When William started bouncing on Mr. Harrison’s thigh, Mr. Harrison passed the child another color and put the red aside. “Nobody stays with the monochrome studies for long, but five minutes must be a record,” he muttered to the child.

While Kit flipped over one card after another in search of a match, Jenny’s heart turned over in her chest. The sensation was physical, painful and sweet, also entirely the fault of the man casually holding one of her nephews and sketching the other.

She’d resigned herself to never having children, and her art, paltry and amateurish though it was, was some consolation. Watching Elijah Harrison casually tuck William closer and retrieve the blue pastel from its trajectory toward the child’s mouth, her resignation came into sharper focus.

The children she’d never have might have been Elijah Harrison’s, or belonged to somebody like him—a talented, handsome man, capable of whimsy and patience. A man willing to sit on the floor and see his trousers attacked by a ferocious, pastel-wielding infant, even as he kept that infant safe and content.

“I found a match, Aunt Jen!” Kit waved the six of clubs and the nine of clubs around. “They can be coachmen!”

It was on the tip of Jenny’s tongue to point out the child’s error. A six and a nine were not a match, not even if they were of the same suit.

“Let me see those.” Mr. Harrison set aside his sketch to pluck the cards from Kit’s hand. While Jenny watched, the artist launched into another little homily about reflections—symmetry by any other name—and Kit forgot all about playing the matching game with his aunt.

Jenny picked up the discarded sketch pad, slid the box of pastels closer, and began to sketch, while William enthusiastically drew green streaks on Mr. Harrison’s trousers.

Six

The Earl of Westhaven steered his horse around a frozen mud puddle, while the Duke of Moreland’s bay gelding splashed right through, indifferent to the breaking ice or cold, muddy water. Westhaven, like his horse, was more of a Town fellow, while the duke longed for the countryside.

“Her Grace is growing restless, sir. I trust you are aware of this?”

Meddling adult children were a loving father’s cross to bear. The duke glanced over at the handsome fellow who was his son and heir. “How is your wife, Westhaven?”

Westhaven rode bareheaded, so His Grace could see his son’s expression take on the sweet, distracted air of a man contemplating the woman about whom he was head over ears. “Anna thrives. She is completely over the birth of our second son, and completely in love with the boy. He’s a quiet little fellow, but sturdy and very alert. Anna says he takes after me.”

“She’s in good health then?”

“As good health as a woman can be when she’s the sole sustenance of a growing boy. It helps that this is not our first. We’re no longer raw recruits to the ranks of parenting.”

With two children still in dresses, Westhaven could wax parental, as if he’d invented the occupation himself upon the birth of his firstborn.

“How many siblings do you have, Westhaven?”

“Seven extant, two deceased, an increasing variety of siblings by marriage. What has this to do with my mother’s discontent, Your Grace?”

Westhaven was a plodder, not given to leaps of intuition but incapable of missing a detail or failing to notice a pattern. When he took his seat in Parliament, England would be the better for it.

Though as a son, he could try the patience of a far more saintly papa than His Grace.

“I have raised ten children with Her Grace and been privileged to partner her in holy matrimony for more than three decades. Do you think I wouldn’t know if the woman were growing restless?”

Westhaven’s lips quirked up in a smile his lady likely found irresistible. As a young husband, His Grace had possessed such a smile, though ten children had rather dimmed its efficacy with their mother.

“I suppose not, sir. I could escort her to Morelands, if that would help.”

“You will do no such thing, Westhaven, nor will you intimate to my duchess that you’ll spirit her away from my side. You will caution your brothers and brothers-in-law not to make any such offer either.”

A rabbit nibbling on a patch of brown winter grass looked up as the horses ambled along the path. Nose twitching, the little beast seemed to weigh the pleasures of filling its belly against the danger of remaining in sight of humans. It snatched another few bites then loped away.

“I confess myself puzzled, Your Grace. You are usually Mama’s slave in all things, and the entire family is to gather at Morelands for the holidays. I don’t know why you’d deny her the pleasure of preparing for our arrival, when she’s so anxious to quit Town and return to Morelands.”

His Grace was not above dissembling when it came to his family, though he’d learned that dissembling was a fraught undertaking where his duchess was concerned. So with his firstborn, he dissembled only a little.

“I haven’t found Her Grace’s Christmas present yet.”

Westhaven’s expression softened. “Your Christmas presents put the rest of us fellows in the shade, you know. Anna won’t even hint what I might give her. If His Grace can come up with such inspired gifts, then surely a small token shouldn’t be beyond me?”

Balderdash. Anna, Countess of Westhaven, was likely already hinting about a little sister for her pair of boys.

“Each year, it becomes more difficult to find something original, something unique. The challenge is to think of a gift your mother hasn’t even admitted to herself she longs for.”

Though she longed to have her family gathered together for the holidays. His Grace could be stone-blind and still see that.

“So you’ll tarry in Town until inspiration strikes?”

“If I must.” And because Westhaven would be Moreland someday, His Grace went on in the most casual of tones. “I don’t think Jenny minds keeping Sophie company while your mother and I are in Town, particularly not when Harrison also bides at Sidling, doing portraits of the little ones.”

Westhaven brought his horse to a halt at a fork in the bridle path. “Harrison? Elijah Harrison? The painter?”

His Grace’s bay came to a halt as well. “Harrison is Flint’s oldest boy, though he’s likely close to your age by now. Fancies himself a portraitist, and when old Rothgreb was grumbling about children growing up too soon, I might have mentioned Harrison to him.”

“Elijah Harrison served as Kesmore’s second at last year’s duel,” Westhaven said. He stroked a hand over his horse’s crest. Westhaven had inherited shrewdness from both sire and dam lines, so His Grace said no more but let his son ponder the puzzle pieces. “Seemed a decent sort. There’s been no gossip about the duel, in any case.”

“I wouldn’t know anything about that, just as I have no idea what I’ll get your mother for Christmas, though I’m scouring the shops until something comes to mind. I trust you’ll pass along any worthy ideas?”

“Of course.” Westhaven looked like he might have a question brewing in his handsome head.

His Grace lifted a hand in parting accordingly. “My regards to your family, Westhaven, and I’ll look forward to seeing you out at Morelands ere long.”

Westhaven saluted with his riding crop and trotted off in the direction of that wife and family, while His Grace considered whether and how best to explain this latest parental gambit to his dear wife. Perhaps she’d have some idea how long two artists might be thrust into each other’s company before the creative passions took over.

Reading Reynolds’s Discourses was getting Elijah nowhere. The grand old style of portraiture—an approach that flattered subjects, carefully posed them, and surrounded them with heroic symbols of great deeds—was fading.

Children had no heroic deeds, in any case. They had sticky fingers, silky curls, and a particular scent, of soap and innocence, that Elijah had forgotten.

The door to Elijah’s sitting room creaked open. His first thought was that a footman, presuming the occupant to be abed, had come to douse the lights and bank the fire.

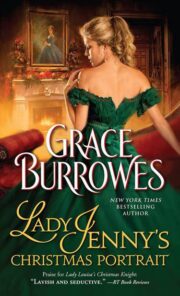

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.