“I agree. It isn’t time, and it may never be time, but I was thinking I might see Lavender Corner put a little more to rights.”

“You are speaking Female on me, Esther. Does this mean you want to double the size of the place or send the servants over to dust?”

“The servants already keep it in good order. I was thinking perhaps I’d make sure the flower gardens were getting proper attention, the linen aired, the sachets kept fresh. A mother sees things a housekeeper cannot.”

He grasped the agenda now. Dense of him not to see it earlier.

“This will require that you jaunt off to Kent posthaste, won’t it?”

“The Season hasn’t started. There’s no time like the present, and I wouldn’t be gone long enough for you to miss me.”

She carried off airy unconcern quite credibly. His Grace wasn’t fooled, but he also wasn’t the only one capable of dissembling in the interests of parental pride.

“I have another idea.” He brought her knuckles to his mouth for a warm kiss. “How about we get a leisurely start tomorrow and break our journey at The Queen’s Harebell?”

He had the satisfaction of seeing her eyes widen and that special smile bloom on her lips.

“Oh, Percy.” She cradled his jaw with her hand and kissed his cheek. “The Queen’s Harebell in spring, the scene of no less an occasion than Chocolate at Midnight. That is a splendid idea.”

Yes, it was, if he did say so himself. Esther rested her head on his shoulder, and the moment became one of a countless number His Grace would hoard up in his heart to treasure at his leisure.

Esther’s smile became a little satisfied—not smug; Her Grace was never smug—and His Grace recognized that once again, she’d achieved her ends without ever having to ask for them.

That she could—and that he almost always spotted it when she did—was just one more thing to adore about her.

Being an upstart, bogtrotting, climbing cit of a quarry nabob was hard work, which Jonathan Dolan minded not one bit.

He thrived on it, in fact, or he did when hard work meant long hours at the quarries, the building sites, and the supply yards. When it meant longer hours, haggling at the negotiation table, poring over ledgers, and hanging about in smoke-filled card rooms, the prospect was much less appealing.

Much, much less.

“If you can’t get your lazy damned crews to put in a full day’s work, that is not my affair. Damages will be assessed per the clause you negotiated, Sloane.”

Sloane paced the spacious confines of the Dolan offices, running a hand through thinning sandy hair while Dolan watched from behind a desk free of clutter.

“The damages will put me under, Dolan. I told you, it isn’t that the crews won’t move your stone, it’s that they can’t move your stone. The rain in Dorset this spring has been unbelievable. This is not bad faith. It’s commercial impossibility.”

The blather coming out of the idiot’s mouth was not to be borne.

“Is that so? The weather is responsible? So we’ve moved from liquidated damages to the commercial impossibility clause?” Dolan kept his tone thoughtful, though even posturing to that extent was distasteful.

Relief shone in Sloane’s squinty brown eyes. “Yes! An act of God, exactly. Torrential rain and no one able to manage. I knew you’d see reason. Hard but fair, that’s what they say about you.”

“Pleased to hear it. Do they also say I’m able to read and write in English?”

They probably speculated to the contrary, but Dolan took satisfaction in seeing Sloane’s gaze grow wary. “I beg your pardon?”

“I can read, Mr. Sloane. I’m sure you’ll be pleased for my sake to learn I can read in several languages. One of them English, though it’s by no means my favorite. And because I own the quarry in Dorset, I also maintain a subscription to the local paper nearest that quarry. Shall I read the weather reports to you?”

Dolan opened a drawer at the side of his desk and pulled out a single folded broadsheet dated about ten days past. “Plowing, planting, and grazing being of central import to much of the shire, the editor is assiduous in his record keeping and prognostication.”

Sloane had sense enough to stop babbling.

“Mr. Sloane, sit down.” Not an invitation, which also should have been a source of satisfaction, considering the man was English to his gloved, uncallused, manicured fingertips.

He dropped into a chair. “I just need a little more time.”

A little more time, a few more potatoes, a little more daylight… The laments were old and sincere, but useless.

“You are late on the deliveries because you do not pay a wage sufficient to attract men who can be relied upon. Because you skimp on wages, your wagons and teams are not properly maintained, and they break down. Knowing you are under scheduling constraints, the smiths, wainwrights, and jobbers take excessive advantage of you when their services are needed on an emergency basis, and once again, to save money, you turn to the most opportunistic and questionably skilled among them.”

He did not add: you are an idiot. He did not need to.

“I have a family.” This was said with quiet desperation, which was probably the very worst aspect of being a quarry nabob. Watching grown men literally sweat while their dignity was sacrificed to their shortsighted greed.

“You also have a mistress, who is likely more for show than anything else. You have too many hunters that you never ride, and you have daughters to launch upward lest your wife have unending revenge on you for your failures.”

Sloane nodded, and Dolan wondered if this was how the priests felt in the confessional: tired, disgusted, and… trapped in their ornate robes and elaborately carved little boxes.

And still Sloane sat there, quivering like a fat, beautifully attired hare waiting for the fox to pounce.

“Lie to me again, Sloane, and I will have your vowels. I will use them to discredit you from one end of the kingdom to the other. You will have no mistress, no stable at all, no fancy clothes, and very likely no family worth the name. You have two weeks before the damages will start to toll. Get out.”

Sloane’s relief was a rank, rancid thing. The odds of the man making a delivery in the next two weeks were not good, but Dolan built slack into every schedule he negotiated, then added more slack, because most of the time, it did rain like hell in Dorset in the spring.

When Dolan was sure Sloane had vacated the entire premises, he grabbed hat, gloves, and cane and left the office, locking the door behind him.

A clerk glanced up from his desk as Dolan passed. “I’m away until tomorrow’s meeting with Ruthven, Standish. Have the files on my desk first thing, send out for crumpets, and dust the damn place before I get here.”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Dolan.”

The day was glorious, almost warm, and brilliantly sunny because the trees weren’t leafed out yet. Dolan strode along in the direction of Mayfair, when what he wanted was to enjoy the day amid the graciousness and privacy of Whitley.

At home more work awaited, a short interlude with Georgina to tuck her in, then more work over a solitary dinner. How was it a quarry nabob felt just as much a slave as if he were still a five-year-old boy, his fingers perpetually cold and muddy from tending the tatties?

The memory was never far from his awareness, which explained in part why he almost plowed over a slight woman carrying some small parcels down the street in the oncoming direction. The parcels scattered, the woman stumbled, and Dolan grasped her by both of her upper arms as she pitched against him.

She righted herself with his assistance, and Dolan found himself looking into a pair of fine gray eyes. “Miss Ingraham. I beg your pardon.”

“Mr. Dolan. My apologies.”

She tried to draw away, but he held her steady. “The fault is mine. I wasn’t watching where I was going.”

Her slightly frayed collar and less-than-pristine gloves added to her usual air of constrained dignity. He let her go and bent to pick up her packages. “I gather today is your half day?”

“Yes, sir. If you’ll just pass me those boxes, I’ll be on my way.”

“Nonsense. Where are you going?”

Her ingrained manners wouldn’t allow her to entirely withhold the information, but she was a female. She could prevaricate, and he couldn’t stop her. Instead, she did the most peculiar thing: she blushed, and she smiled. “I was going to the park.”

The park, a monument to England’s democratic leanings, a place where anybody could enjoy fresh air and sunshine. Dolan cast back and could not recall seeing that quiet smile on any previous occasion. That smile went well with her fine gray eyes and exceptional figure. “Then we’ve a bit of a walk ahead of us.”

He tucked her packages under one arm and winged the opposite elbow at her, and damned if the infernal woman’s smile didn’t fade to be replaced by a look of reproach.

“Mother of God, it’s simply a courtesy, Miss Ingraham. It isn’t as if you’re the scullery maid.”

Her spine straightened, she wrapped her hand around his arm, and they moved off, leaving Dolan with a rare opportunity to observe his daughter’s governess outside the child’s presence.

“Have you been shopping?” Inane question, of course she had. Dolan wished again his late wife might have spent more time teaching him the difference between interrogation and small talk, for he’d yet to grasp the distinction.

“Just a few personal things. This really isn’t necessary, sir.”

He did not reply—let her be the one to demonstrate some conversational skills. He was sure she had them, though whether she’d take pity—

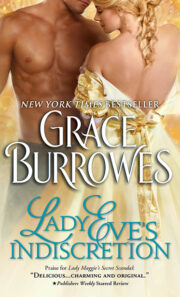

"Lady Eve’s Indiscretion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Eve’s Indiscretion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Eve’s Indiscretion" друзьям в соцсетях.