“Captain Corder, you’re a caution, that’s what you are!” So said Tom Entwhistle many a time to Uncle Dick.

I had discovered that Uncle Dick wanted me to grow up exactly like himself; and as that was exactly what I wanted to do we were in accord.

My mind was wandering back to the old days. Tomorrow, I thought, I’ll ride out on to the moors . this time alone.

How long the first day seemed! I went round the house into all the rooms—the dark rooms with the sun shut out. We had two middle-aged servants, Janet and Mary, who were like pale shadows of Fanny. That was natural perhaps because she had chosen them and trained them.

Jemmy Bell had two lads to help him in the stables and they managed our garden too. My father had no profession. He was what was known as a gentleman. He had come down from Oxford with honours, had taught for a while, had had a keen interest in archaeology, which had taken him to Greece and Egypt; when he had married, my mother had travelled with him, but when I was about to be born they had settled in Yorkshire, he intending to write works on archaeology and philosophy; he was also something of an artist. Uncle Dick used to say that the trouble with my father was that he was too talented; whereas he. Uncle Dick, having no talents at all, had become a mere sailor.

How often had I wished that Uncle Dick had been my father!

My uncle lived with us in between voyages; it was Uncle Dick who had come to see me at school. I pictured him as he had looked, standing in the cool white-walled reception room whither he had been conducted by Madame la Directrice, legs apart, hands in pockets, looking as though everything belonged to him. We were much alike and I was sure that beneath that luxuriant beard was a chin as sharp as my own.

He had lifted me in his arms as he used to when I was a child. I believed he would do the same when I was an old woman. It was his way of telling me that I was his special person . as he. was mine. ” Are they treating you well?” he said, his eyes fierce suddenly, ready to do battle with any who were not doing so.

He had taken me out; we had clip-clopped through the town in the carriage he had hired; we had visited the shops and bought new clothes for me, because he had seen some of the girls who were being educated with me and had imagined they were more elegantly clad than I. Dear Uncle Dick! He had seen that I had a very good allowance after that, and it was for this reason that I had come home with a trunk full of clothes all of a style which, the Dijon couturiers had assured me, came straight from Paris.

But as I stood looking out on the moor I knew that clothes could have little effect on the character. I was myself, even in fine clothes from Paris, and that was somebody quite different from the girls with whom I had lived intimately during my years in Dijon. Dilys Heston-Browne would have a London season; Marie de Freece would be introduced into Paris Society. These two had been my special friends; and before we parted we had sworn that our friendship would last as long as we lived. Already I doubted that I should ever see them again.

That was the influence of Glen House and the moors. Here one faced stark truth, however unromantic, however unpleasant.

That first day seemed as though it would never end. The journey had been so eventful, and here in the brooding quietness of the house it was as though nothing had changed since I had left. If there appeared to be any change, that could only be due to the fact that I was looking at life here through the eyes of an adult instead of those of a child.

I could not sleep that night. I lay in bed thinking of Uncle Dick, my father. Fanny, everyone in this house. I thought how strange it was that my father should have married and had a daughter, and Uncle Dick should have remained a bachelor. Then I remembered the quirk of Fanny’s mouth when she mentioned Uncle Dick, and I knew that meant that she disapproved of his way of life and that she was secretly satisfied that one day he would come to a bad end. I understood now. Uncle Dick had had no wife, but that did not mean he had not had a host of mistresses. I thought of the sly gleam I had seen in his eyes when they rested on Tom Entwhistle’s daughter who, I had heard, was ” no better than she should be.” I thought of many glances I had intercepted between Uncle Dick and women.

But he had no children, so it was characteristic of him, greedy for life as he was, to cast his predatory eyes on his brother’s daughter and treat her as his own.

I had studied my reflection at the dressing-table before I got into bed that night. The light from the candles had softened my face so that it seemed—though not beautiful nor even pretty—arresting. My eyes were green, my hair black and straight; it felt heavy above my shoulders when I loosened it. If I could wear it so, instead of in two plaits wound about my head, how much more attractive I should be. My face was pale, my cheek-bones high, my chin sharp and aggressive. I thought then that what happens to us leaves its mark upon our faces.

Mine was the face of a person who had had to do battle. I had been fighting all my life. I looked back over my childhood to those days when Uncle Dick was not at home; and the greater part of the time he was away from me. I saw a sturdy child with two thick black plaits and defiant eyes. I knew now that I had taken an aggressive stand in that quiet household; subconsciously I had felt myself to be missing something, and because I had been away at school, because I had heard accounts of other people’s homes, I had learned what it was that young child had sought and that she had been angry and defiant because she could not find it. I had wanted love.

It came to me in a certain form only when Uncle Dick was home. Then I was treated to his possessive exuberant affection; but the gentle love of a parent was lacking.

Perhaps I did not know this on that first night; perhaps it came later; perhaps it was the explanation I gave myself for plunging as recklessly as I did into my relationship with Gabriel.

But I did learn something that night. Although it was long before I slept I eventually dozed to be wakened by a voice, If and I was not sure in that moment whether I had really heard that voice or whether it came to me from my dreams.

“Cathy!” said the voice, full of pleading, full of anguish. ” Cathy, come back.”

I was startled—not because I had heard my name, but because of all the sadness and yearning with which it was spoken.

My heart was pounding; it was the only sound in that silent house.

I sat up in bed, listening. Then I remembered a similar incident from the days before I had gone to France. The sudden waking in the night because I had thought I heard someone calling my name!

For some reason I was shivering; I did not believe I had been dreaming.

Someone had called my name.

I got out of bed and lighted one of the candles. I went to the window which I had opened wide at the bottom before going to bed. It was believed that the night air was dangerous and that windows should be tightly closed while one slept; but I had been so eager to take in that fresh moorland air that I had defied the old custom. I leaned out and glanced dowr at the window immediately below. It was still, as it had always been, that of my father’s room.

I felt sobered because I knew what I had heard this night, and on that other night of my childhood, was my father’s voice calling out in his sleep. And he called for Cathy.

My mother had been Catherine too. I remembered her vaguely—not as a person but a presence. Or did I imagine it?

I. seemed to remember being held tightly in her arms, so tightly that I cried out because I could not breathe. Then it was over, and I had a strange feeling that I never saw her again, that no one else ever cuddled me because when my mother did so I had cried out in protest.

Was that the reason for my father’s sadness? Did he, after all those years, still dream of the dead? Perhaps there was something about me which reminded him or her; that would be natural enough and was almost certainly the case. Perhaps my homecoming had revived old memories, old griefs which would have been best forgotten.

How long were the days; how silent the house! Ours was a household of old people, people whose lives belonged to the past. I felt the old rebellion stirring. / did not belong to this house.

I saw my father at meals; after that he retired into his study to write the book which would never be completed. Fanny went about the house giving orders with hands and eyes; she was a woman of few words but a click of her tongue, a puff of her lips, could be eloquent. The servants were in fear of her: she had the power to dismiss them; I knew that she held over them the threat of encroaching age to remind them that if she turned them out, there would be few ready to employ them.

There was never a spot of dust on the furniture; the kitchen was twice weekly filled with the fragrant smell of baking bread; the household was run smoothly. I almost longed for chaos.

I missed my school life which, in comparison with that in my father’s house, seemed to have been filled with exciting adventures. I thought of the room I had shared with Dilys Heston-Browne; the courtyard below from which came the continual sound of girls’ voices; the periodic ringing of bells which made one feel part of a lively community; the secrets, the laughter shared; the dramas and comedies of a way of life which in retrospect appeared desirably lighthearted.

There had been several occasions during those four years when I had been taken on holiday trips by people who pitied my loneliness. Once I went to Geneva with Dilys and her family, and at another time to Cannes. It was not the beauties of the Lake which I remembered, nor that bluest of seas with the background of Maritime Alps; it was the close family feeling between Dilys and her parents, which she took for granted and which filled me with envy.

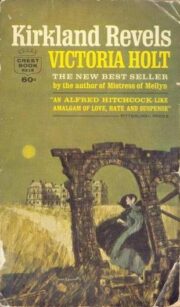

"Kirkland Revels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Kirkland Revels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Kirkland Revels" друзьям в соцсетях.