She turned quickly from him, and recoiled as she saw the gibbet. Two rotting half-naked bodies dangled from the nooses. Katherine took one shrinking look and recognised - despite the bloated livid features - the long skull and jaw of Sim Tanner, the reeve. She gave a horrified cry and the steward said, "Ay, my lady. Sim took to thieving and poaching as soon as I turned him from his reeveship. Had got used to little luxuries no doubt, and wouldn't give 'em up."

So Sim had escaped Nirac's dagger so long ago, to end finally like this. The fog swirled thickly in from the Trent, Katherine's teeth chattered with another chill and she had hastened back to the dubious warmth of the Hall. Later she had ordered that Cob be freed from the stocks, and that his plot of land be restored to him, for she had been sickened by all the sights on the village green.

Dear Mother of God, how she had detested Kettlethorpe, and been in a frenzy to get away again.

But now she remembered that Blanchette had not. The girl had visited all the haunts of her childhood, the Broom hills, the mill, the river ford and a little pool where she had once played with village children. As though some inner sluice gate had been raised, Blanchette had asked a spate of eager, shy questions about her father. Was it here in the Hall that his armour had hung? What had been his favourite horse's name? And she had said, "How old was I, Mama, when Father kissed me good-bye here on the mounting b-block, the last d-day I ever saw him when he left for Aquitaine?"

Katherine had answered that Blanchette must have been about three and it was a wonder she remembered.

"I d-do remember," said Blanchette with a sad yet excited little smile. "God rest my dear brave father's soul."

Katherine, light-headed with her own illness and profoundly discomfited by all these sights and memories, had paid little attention. She realised that both children thought Hugh had died of wounds sustained in glorious battle, since no details had been given them. But it was true enough the dysentery had been a kind of battle wound. There was no falsehood in that.

"Ay - I remember now," said Katherine, finishing her thoughts aloud to Hawise, "that Blanchette wept when we left that odious place. But I feel 'tis morbid. She has everything to make her happy now in this new life the Duke has given her. I'll certainly take a firmer hand, as he wishes."

Katherine's face cleared and she waved away the huge gauzy gold-horned headdress that Hawise lifted up. "Let be, for now," she said, smiling. "One would think I'd no other children but that naughty little wench. I'll not frighten the babies with that foolish thing, and I'm off to the nurseries. How are Joan's gums, poor mite?"

"Sore as boils, I'll warrant, from the uproar she do make," answered Hawise dryly. "She yells louder'n any o' her brothers did."

Katherine laughed, and the two women walked down the passages to the nursery wing. John and Harry had long since gone out to play in the snow with other castle children, but her two latest-born were sitting on a bearskin rug by the fire.

Thomas, so christened because he had been born on St. Thomas a Becket's Day, but called Tamkin to differentiate him from his half-brother, Tom Swynford, was engaged in playing some private game with a set of silver chessmen the Duke had given him. Joan was solemnly chewing on a bone teething-ring. Both children squealed with delight when they saw their mother. Tamkin jumped up, and the baby held out her arms.

If anything should happen to John, what would become of the - Beaufort bastards? She crossed herself and sat staring into the fire, while the baby gurgled drowsily on her lap, Hawise and the nurses came and went at their tasks, and Tamkin, tiring of his game, ran off to find his greyhound puppies.

Even with the Duke's protection, what future did they have? The boys might be knighted in due course by their father, and make their own way as best they could with the appointments he could give them, but they might not aspire to honours. And the baby Joan - -

It would take a stupendous amount of dowry to get her married properly. Few worthy noblemen would overlook the stain of bastardy.

But if it should happen somehow - in terror, her mind veered from facing the actual thought again - that John could not see to their future, who would protect them then? Not the childish, self-centred Richard, nor the Princess. Certainly not the Earl of Buckingham. Edmund might make a feeble gesture, but when did Edmund's vacillating impulses ever persist for long? It was a treacherous marshy ground over which she had so blithely walked, thinking it firm as granite.

She looked at the baby in her lap, at Tamkin, who was trying to teach one of his puppies to beg. She thought of her two handsome gently bred older boys, who were being reared like young princes. But they were not. They had no legal name, no certain inheritance of any kind, and no sure future but herself. Blessed Mary, she thought, and what could I do for them, alone?

She stilled her panic and forced her mind to a practicality that was repugnant to it. Deliberately she scrutinised the total of her few possessions. The Duke from time to time had given her property, which she had accepted with reluctance, disliking the idea of payment for her love. The private income that these brought her she had scarcely heeded, it was but an insignificant trickle of pocket-money compared to the lavishness in which she lived.

She had the meagre Swynford inheritance, of course, though it was distasteful to her. Besides, it would belong eventually to Tom. She had a yearly hundred marks as governess's recompense, but that would shortly stop, since Elizabeth was married and Philippa beyond the age. She owned houses in Boston, which brought in a small rent. She had two wardships, including the Deyncourt one for Blanchette, some perquisites from the Duke's Nottingham manors, and that was all, except her jewels.

We could never live on that, thought Katherine, frightened. We'd have less than yeoman status. And she determined at least to accept the new wardship and "marriage of the heir" John had semi-humorously offered her.

" 'Twill be appropriate, Katrine. A neat turnabout for the insolence he showed you."

Ellis de Thoresby, Hugh's erstwhile squire, had been killed in a drunken brawl three months ago, leaving a two-year-old son. It was the fat annual fee for guardianship of this son that John offered her, and she refused sharply. She had neither seen nor heard of Ellis since he spat at her in the streets at Lincoln. She wanted no reminder of him.

Ah, but I must be practical, thought Katherine. I've been a soft fool. It was not mercenary to try and protect her children's future, and when the right moment came she would talk to John about it. The moment must be chosen, for though he was generous, he preferred to think of such things himself, and she knew that he might be angered that she should seem to question the provision he intended some day to make for all his children. And he would be right, she thought with sudden revulsion. She could not appear to grasp and scheme as though she had forebodings for him. There was no danger that could threaten them when she had the certainty of his love. She would go on as she had been, nor worry about the future.

Katherine picked up the baby and put her in the cradle, then looking around to find the source of an exceptionally wintry draught, saw that Tamkin had opened the leaded window and was hanging half-way out.

"Tam," she called, "what are you doing! Shut the window!"

The boy did not hear her, for there was much noise outside. The nursery windows looked down on Castle Street, where a cluster of rustics and townfolk had gathered, while a man in a long russet gown stood on a keg and harangued them.

" 'Tis only some Christmas mumming," said Katherine impatiently, shutting the window.

"Nay," said Hawise peering over the little boy's shoulder, " 'tis that Lollard preacher, John Ball, just come to Leicester, I hear. He's been jabbering and havering since Prime. I don't much like the look o' it."

"Why ever not?" said Katherine in surprise. "No harm in preaching."

"They keep singing something, Mama," said Tamkin, "over 'n' over, 'n' shaking their fists."

"They do," said Hawise grimly. "D'ye know what they sing?"

Katherine looked out again more curiously. She saw that the preacher had a fiery red face between a black beard and a crop of black hair on a round head, that he waved his arms violently and sometimes struck his russet-clad breast, pointing up to the sky, and then at the castle. Now and again he would stop with both arms wide outflung, when all the crowd of folk would stamp their feet and chant something that sounded like the rhythmic pound of a hammer on a smith's anvil.

"What do they sing?" Katherine said and opened the window wide. The hoarse pounding shouts gradually clarified themselves into words:

When Adam delved and Eva span,

Who was then the gentleman!

"What nonsense!" began Katherine - and checked herself. "What do they mean by that?"

"They mean trouble," said Hawise. "This last poll tax has really roiled 'em, and John Ball's doing his best to keep 'em roiled - throughout the land."

"Oh," said Katherine shrugging as she turned from the window. "The poll tax is hard on folk, no doubt, but wars must be paid for, Hawise. Why must they show so much hatred?"

" 'Tis easy to hate, lady dear, when you be poor and starving."

"But they're not!" cried Katherine, her eyes flashing. "Nobody starves in Leicester, or any of the Duke's domains. The kitchens often feed three hundred a day."

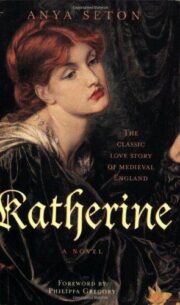

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.