"Perhaps," whispered the girl. She shut her eyes. Her mind formed no prayer, she importuned no saints nor even the Blessed Virgin for help, and yet it seemed that some new calm strength came to her.

The Princess rushed to the door. They went out together and down the newel stairs to the courtyard.

The Duke, in brass helmet and full armour, his hand resting on his sword, stood by the river gate shouting last instructions to Percy: "Then by dawn we'll have raised a thousand men between us, 'twill do for now. The Savoy - -"

He stopped and stared, as Katherine came up to him. "My lord - -"

So full was he of his new plans that at first it seemed he did not know her. Beneath his lifted visor his face was set and haggard, his eyes the sharp ice-blue she had always feared.

She looked at him softly, but she spoke with the force that had come to her. "My lord, I must see you alone now."

"Katrine!" he said bewildered. "What do you here? You were at the Savoy - nay, in Billingsgate - I remember Robin Beyvill said you sent him. 'Twas not well done, they were in no danger here at Kennington. I would have faced them down in London, they'd not have dared to touch me,"

"My dearest lord," said Katherine, looking steadily up into his face, "I wish to see you alone."

"What tiresome folly!" He jerked his mailed hand on his sword hilt. "I'm off to the Savoy. My men are gathering, and I've other work to do this night."

Katherine drew herself high, her chin lifted and she said inflexibly, "All this will wait until you've talked with me. I command it, my lord."

"Command!"

"Yes," she said unflinching. "By reason of this you gave me." From her purse she drew the sapphire ring and held it out to him on her palm. "And this is the first thing I have ever asked of you, my lord."

He looked at the ring, and then at Katherine.

He turned impatiently to Percy. "You go on ahead. I'll follow shortly. Now, Katrine, what do you wish of me?"

The Princess saw that the first battle had been won and came forward hastily. "There's a fire in the State Chamber, my lord, you can talk to Lady Swynford there. I'll send food and drink to you, for you've not eaten all this day - -" She saw his face darken, and added with the desperate guile she had often needed for her Edward, "Supper will give you more strength and a clearer head for whatever it is you plan to do tonight."

John frowned, but he walked over to the stairs without comment. The women followed, while the Princess pulled Katherine a little behind. "God help you, child," she whispered, "and Saint Venus help you too. You'll have need of every help to turn him from his purpose. Make him drink much - and - by Peter, I wish there were time to dress you in one of my silk chamber gowns, though 'twouldn't fit - no matter, you must know the ways to make him think of love. Woo him, cajole him, weep - -"

"Dear madam," whispered Katherine, "I'll do what I can." But not for you nor me, nor England, she thought, but because he is destroying his own soul.

She entered the State Chamber and the Duke turned sharply on her. "What would you say to me, Katrine - I've little time."

"Time enough to rest a bit though, my lord. And I can't talk to a man standing in full armour, 'tis frightening." She gave him a gay coaxing smile, though her heart beat fast.

He grunted and sat down on the wide oak chair where his brother had used to sit. She went to him and quickly unhooked the latchet of his brass helmet and lifted it off his head. "And you can't eat in these," she said, unbuckling the straps that fastened his mailed gauntlets. "Here comes Robin with wine - won't you let him take off the rest of your armour? 'Twill be quickly donned again when you wish to leave."

She gestured to Robin, for still John did not speak.

He was fighting a great weariness that had come on him when he sat down. He had not slept in two nights, the first at Percy's Inn, the second here. His head swam, and because it blunted his purpose, he fought off too the realisation of how strongly he had responded to Katherine's touch as she drew off his helmet.

He suffered Robin to unbuckle the other sections of his armour and hang them with his great sword from gilded wall pegs where the Prince of Wales' black tilting gear still hung. Then he took the cup of wine that Katherine brought him and drank quickly.

As he had hoped, it cleared his head. "What are you doing at Kennington?" he said scowling. "Why didn't you wait at the Savoy to see me?"

Katherine considered quickly. Robin and the server were gone and she was preparing a plate of food. She had never lied to him, nor would she, but she knew that she must choose all her words with care.

"It is not always so easy to see you at the Savoy, my lord," she said, pulling a corner of the table over so that he might eat in comfort, "nor for me to see you at all - of late." She smiled, with no hint of reproach, and sat down close to him on a stool. "You look very tired, won't you eat, please? Alas that 'tis only Lenten fare, but these oysters are well roasted."

He started to protest hotly, to say that if she had forced him to delay his start simply to babble of oysters, he would be gone this instant, but instead, and to his astonishment, he said a very different thing.

"Why don't you wear the ring I gave you, Katrine?" She had dropped it back into her purse as they left the courtyard.

She was startled too, but she answered evenly, "Because I thought that it had lost its meaning."

A quick dull flush mounted his thin cheeks. "Nay, how could you think that, lovedy?" The little pet name which he had so often called her slipped out as unawares as had his question, yet he felt aggrieved. Whether he saw her or not, he had known her ever there in the background - waiting, like his jewelled Order of the Garter, seldom worn, yet the possession of this most special badge of knighthood was of steady importance to his life. "I have had matters to think of," he said roughly, "but these matters had nothing to do with women."

"Yes," she said, filling his cup, "I believe that now, my lord."

She brushed against his shoulder as she put the flagon back on the table, and he smelled the warm fragrance of her skin. His arm lifted of its own accord to slip around her waist and pull her closer to him, but she moved away before he touched her and sat down again.

His arm dropped. He drank, and spooned up the oysters, eating fast, for he found that he was famished and this the first food in weeks that had had savour for him. While he ate, he felt another new factor, a quality of rest and lessening of strain. He resented the thought that this easing came somehow from Katherine, who sat beside him quietly, gazing into the fire. He had forgotten too how beautiful she was, nor did he wish to think of it now.

He picked up the gold-handled table knife and cut himself a slice from the bread loaf, while pulling his mind back towards his purpose. They were massing at the Savoy, men-at-arms from his nearby castles at Hertford and Hatfield. They'd be there by now since he had sent messengers off at dawn, and the King's guard from Sheen too. It would take a month to gather all his forces from the whole of England, but already' he had sufficient fighters to back the first move that he would make.

Pieter Neumann - he threw down the bread and his fingers gripped the hilt of the knife. This time he would kill Pieter with his own hand - no mercy.

Katherine had turned to look at him as he threw down the bread and gripped the knife and she forced a long steady breath to master her dismay. She saw that he had lost awareness of her, his skin had turned the colour of mould, he swallowed hard and painfully, and in his eyes as they stared at the knife the pupils had swollen so that there was no blue.

Katherine felt a shock of recognition. Somewhere there had been a child who looked like that, an uncomprehending terrified child. She searched hard for the memory, and when it came it seemed to her so incongruous that she rejected it. The reminder was of her little John. Last summer he had wandered into the cow-byre at Kenilworth, and a playful calf had galloped at him, knocking him down. The child had believed the calf to be a werewolf, fitting it somehow into a horrible tale a serving-maid had told him.

Katherine had reasoned with her boy, had made him pet the calf, and got him to laugh at his terror, yet a month afterwards the child had had a nightmare from which he awoke to scream that the calf was after him with the slobbering fangs and blood-red eyes of a werewolf, and still when he saw a calf he trembled and grew white.

It were folly indeed to make a comparison between the thirty-six-year-old Duke of Lancaster and a four-year-old child, and yet - in both she had seen the same intrinsic shape of fear.

The Duke stirred and put down the knife, he wiped his lips on the damask napkin. "I must go," he said in a voice that wavered. He stood up and glanced towards his armour.

Katherine rose too, and took his hand in hers. "Why must you go, John?" She looked up solemnly into his resistant face. "Is it to kill the man who is in sanctuary at Saint Paul's? Is it to do sacrilegious murder, that you must go?"

He snatched his hand from hers. "How do you know that? And if it were, what right have you to question me? Katrine, you've never before - get out of my way!" For she had backed so that she barred the way to the armour, and the door.

Her wide grey eyes fixed on him with compassion, but her tone was cool and searching as when she rebuked her children; "Of what, my dear lord, are you so afraid?"

He gasped and raised his hand as though to strike her.

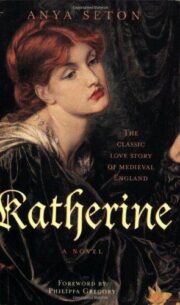

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.