He flung himself on to his horse and pursued by two of his squires galloped along the Strand to Westminster.

After the day's session, he dined in the Hall with many of the lords. Percy of Northumberland sat on his right. They had much to discuss about Wyclif's trial tomorrow at St. Paul's, and the showdown with Bishop Courtenay.

"But," said the Duke, sipping without relish some very fine malmsey, "we must be temperate, Percy. Wyclif should be his own best advocate."

Northumberland irritably hunched his massive shoulders, while he speared himself a gobbet of smoking sturgeon from the platter offered him by his kneeling son, who was acting as his squire. The baron crammed his mouth full, sputtered with pain and spewed the fish out on to the rushes.

"Sweet Christ! M'tongue's burned off!" He clouted young Percy violently on the ear.

His thirteen-year-old son had a temper to match. " 'Tis not my fault, my lord, an you gobble like a swine!" he cried, throwing down the platter.

Father and son glared at each other. The blue Percy lions on their sutcotes jigged in and out with their fierce breathings. Then the baron thwacked his heir across the shoulder, upsetting him into the filthy rushes. "Hotspur, Hotspur!" he roared, slapping his thigh. He turned to the Duke, "Saw you ever such a game cockerel - dares flout its own sire!"

"Certainly your young Hotspur shows a spirit which will be useful to keep the Scots in order," said the Duke dryly, thinking of his own Henry's excellent manners.

"Ay - the Scots-" said Northumberland, rinsing his blistered mouth with wine. "First we must keep London in order."

"You cannot tamper with the City's liberties," said the Duke firmly. They had been through this before. Percy, as new Marshal of England, was continuously annoyed that the City did not admit his jurisdiction.

"Hen piddle!" cried Percy. "That pack of baseborn tradesmen - what right have they to liberties? Let the mayor stick to his needles and threads, 'tis all he's fit for."

"If you abolish the mayoralty and take to yourself the ruling of the City, do you think the Londoners'll submit?"

"By the rood, they'd have to! Jam the bill through Parliament, through their own Commons. They've awe enough of that!"

The Duke turned away. His ally's loud voice rasped on him. The headache which had plagued him all morning began to throb. He longed for sleep, and roused himself with an effort.

Later that afternoon as London church bells were ringing for vespers the Duke and Lord Percy rode into the City bound for the tatter's town residence at Aldersgate. This mansion was but a few hundred yards beyond St. Paul's, and it had been decided to use it for headquarters.

En route from Westminster to the City, the Duke had stopped at the Savoy to pick up certain of his men and Brother William Appleton. The Franciscan, now fully reinstated in the Duke's favour, was to be one of Wyclif s advocates. The other three - a Carmelite, a Dominican and an Austin - were to meet them at Percy's "inn".

They crossed the wide market-place at West Chepe. All the booths and stalls were battened down now, and only the lowing of penned cattle from the shambles disturbed the quiet. They entered St. Martin's Lane, and at the bend where it narrowed by the Goldsmiths' Hall the Grey Friar suddenly saw three figures in the gloom ahead. Startled, he stood up in his stirrups and peered over the Duke's shoulder. There was still light enough to recognise two black-habited monks and a third shorter man in a dark cleric's robe. The three figures paused and wavered in a moment of obvious confusion, when they saw the horsemen approaching. Brother William caught the flash of something white and stiff being thrust into the clerk's sleeve.

"My lord!" cried the Grey Friar, "we must catch that man!" He kicked his mule and clattered past the astonished Duke, the two monks swivelled and, hiking up their robes, pelted as fast as their legs would take them towards Aldersgate. The clerk limped frantically behind, while his head jerked this way and that searching for cover.

The friar overtook the hobbling figure as it was about to dart into an alley, and swooping down with a long arm, collared a handful of cloth.

The Duke galloped up as the struggling clerk had nearly freed himself and, leaning from the saddle, grabbed the man's wrist. "What's this, Brother William?" cried the Duke with some amusement, his powerful grip tightening on the plunging wrist. "What games do we play with this wriggling little whelp? I never knew you so sportive."

The friar had flung himself off his mule, and plunged his hand into the clerk's sleeve. He brought out a roll of white parchment and squinted down quickly in the waning light.

"This is the man, my lord, who wrote the placard on Saint Paul's door," he cried.

The Duke started, his grip loosened, and the clerk, twisting suddenly free, would have made off but a score of retainers had come up, and he was surrounded. He stood still in the central gutter and pulled his hood down over his face.

"Bind him," said the Duke in a deadly quiet voice. A squire jumped forward with a leather thong and tied the clerk's wrists behind his back.

"Take him to my inn!" cried Lord Percy. "We'll deal with him there."

The clerk suddenly found his voice. "You can't," he shrilled. "You haf no right to touch me! I know my rights. I claim the City's protection!"

"Hark at him!" roared Percy. "Hark who speaks to the Marshal of England. Take him, men!"

The clerk was picked up and rushed down the street to Percy's gate. The Duke and Percy followed. The courtyard gate closed behind them. They dragged the clerk into the house and flung him down on the floor of the Hall. He hitched himself slowly to his knees, then to his feet. He stood swaying; his chin sunk on his chest, his bound hands opening and closing spasmodically behind his back.

The retainers of both lords crowded around, staring curiously, eager to inflict more punishment. As it was, blood dripped from the long ferrety nose, and a lump big as a chestnut rose from the bald spot on the tonsure.

"We'd best flog him, afore he's put in the stocks," said Percy with relish. "What's he done, by the way?" He looked at the Duke, who was standing six feet from the clerk and regarding him fixedly.

The Duke held his hand towards the friar without answering, and Brother William gave over the large square of parchment.

"Bring me a light," said the Duke. A varlet ran up with a torch. The rustlings and murmurings ceased, the Hall grew still while they watched the Duke read, until he raised his head and said, "This time it seems that I - John of Gaunt - for reason of my base birth am therefore without honour, so have made secret treaty with King Charles of France to sell him England."

There were a few gasps, Percy's red face grew redder, but nobody moved. The Duke took the torch from the varlet and bending down held it near to the prisoner.

"Let me see your face!"

The clerk's knees began to quiver, he hunched his shoulders higher around his ears and the sound of his breath was like tearing silk.

The Duke knocked his head up with a blow of the fist beneath the chin and stared down by the torchlight. Suddenly he reached out and yanked the clerk's collar from his stringy throat. A jagged white scar ran from the jaw to the Adam's apple.

"And so it is you, Pieter Neumann," said the Duke softly. He handed the torch back to the varlet. "You still bear the mark a boy made on you thirty years ago at Windsor."

"I don't know what you mean, Your Grace. I am Johan, Johan Prenting of Norvich. This scar is from a wound I got in France, I fought well in France for England, Your Grace. I know not what is on the parchment, it vas the monks at St. Bart's wrote it. I've done no harm - -"

"He lies, my lord," interrupted Brother William solemnly. "For I myself saw him writing on the parchment."

"He lies - -" said the Duke. "As he always lied - lied - -" he repeated, but in the repetition of the word, the friar heard a wavering. He noted this with astonishment. What could it be that the Duke doubted, what uncertainty had caused that stumbling inflexion, and what earlier association could there have been between these two?

"We'll hang him!" cried Lord Percy, who had finally comprehended the situation. "Haul him out to the courtyard!" Four of his men sprang forward.

"Wait - -" The Duke held up his hand. "Take him to some privy place, put him in the stocks. I would talk to him alone first."

Percy's men hustled the clerk through the kitchens and below stairs to the cellars, where in the darkness there was a small dungeon. The clerk's wrists and ankles were clamped into the holes in the wooden stocks, and the men pulled savagely on his twisted leg to make it fit in the hole.

The Duke had followed them. He watched impassively while the prisoner groaned and cursed and tried to ease his dangling rump on the dungeon paving-stones. Then he said, "Leave a torch in the bracket and go." Percy's men obeyed. The Duke, clanging shut the iron door, leaned against the wall.

"You suffer now, Pieter Neumann," he said, "but you will suffer far more than this before you die, if you don't speak truth to me. Where have you been since that day at Windsor Castle when you did steal your mother's purse and ran away?"

Pieter's eyes slithered to a heap of rusty chains and fetters and he said sulkily, "In Flanders."

"Where?"

"In Ghent jail and at the Abbaye de Saint Bavon vere you were born, Your Grace. The monks taught me to write." A sly hope came to him as he noted a change in the Duke's face when he mentioned the abbey. He rested his chin on the rough plank-top of the stocks and waited.

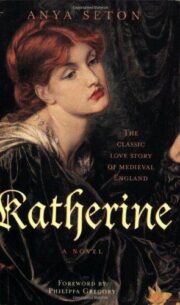

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.